Praet says rates can still go lower

Autor: Bancherul.ro

Autor: Bancherul.ro

2016-03-20 14:01

Interview with Peter Praet, Member of the Executive Board of the ECB, conducted by Ferdinando Giugliano and Tonia Mastrobuoni on 15 March 2016 and published on 18 March 2016:

Can you explain why you took such a big package of measures last Thursday?

You have to put these decisions in the context of heightened risks to our price stability objective. External shocks, mainly originating from emerging markets, high market volatility and the crucial need to avoid second-round effects warranted a strong and comprehensive package to counteract these adverse forces.

We don’t have a gloomy assessment of the economy, domestic conditions have improved, financial conditions have clearly improved. But it is still very fragile, and external shocks can easily trigger a vicious circle, with further downward pressure on inflation. We wanted to ensure that this did not happen, in line with our mandate. It was decided by the vast majority in the Governing Council, that we had to act very forcefully to ensure an even more accommodative monetary policy stance.

What can be said about the composition of the measures?

We discussed the pros and cons of the different measures. On the negative deposit rate: it is clear that it served us very well in the past, it has been quite efficient in easing financial conditions, including the exchange rate, as a natural by-product of differences in the monetary policy stance in the major currency areas. As we proceeded on the path of negative interest rates on our deposit facility, it was also clear we had to look at the impact on the profitability of the banks.

Banks are very important for the monetary transmission mechanism, so you have to look at what is the impact of the package on the banking sector. Against this background, we decided in favour of a package which still made use of changes in the ECB interest rates but increased the weight of measures aimed at credit easing.

Since the markets had already anticipated three cuts in the deposit rate this year many money markets traders had to turn their positions. However, with a little bit more time to scrutinize and digest the complex package, markets and analysts finally tuned again.

Were you surprised by the strength of the market reaction?

I expected that the short end was going to be repriced but that the rest of the package would dominate. Looking through some volatility, what we have got at the end makes sense from an economic point of view.

Basically, we had a substantial impact on credit markets, which is good as financial conditions were worsening and credit spreads were going up. What dominated was very much the TLTRO and the broadening to corporate bonds of the asset purchases.

In terms of other asset prices, I believe markets are very conscious already that the monetary policy courses of the major world currency areas remain quite on different trajectories as they reflect fundamentally different domestic underlying conditions. As we have said few times in the past, the fact that there are significant and increasing differences in the monetary policy cycle between major advanced economies will become ever more evident in the near future.

But do you think the market is right to believe there will not be more cuts?

In the Introductory Statement we said very clearly that we “expect the key ECB interest rates to remain at present or lower levels for an extended period of time, and well past the horizon of our net asset purchases.

So you haven't reached the lower bound?

No, we haven't. As other central banks have demonstrated, we have not reached the physical lower bound. This re-composition of the tool-box does not mean that we have thrown away any of our tools. If new negative shocks should worsen the outlook or if financing conditions should not adjust in the direction and to the extent that is necessary to boost the economy and inflation, a rate reduction remains in our armoury.

On corporate bonds purchases: would this instrument be accessible for companies like, let's say, Volkswagen?

Yes, as long as they have investment grade. You have corporate bonds in other sectors too, such as utilities, insurance, telecommunications, energy.

Don't you think you are entering the dangerous territory of choosing who to distribute money to? For example, you may end up favoring larger companies.

Normally what you do is that you give liquidity to the bank in exchange of collateral. Here, you take a direct exposure. The other point is, you want to avoid influencing relative prices. We asked the committees to work on the specific definition of the bonds we will buy. We could buy something that is close to the index, but excluding banks, so that we avoid price distortions in the corporate bond market.

The important point is that if the price goes up because you are buying non-financial corporations, there will be search for other bonds by the markets participants so they will rebalance the portfolio with other bonds that are not in our portfolio. So the initial effect of our purchases will spread further and the market can still function.

Can we put it like this: in countries like Germany and France with big companies with high ratings, you are helping with corporate bond purchases, and in countries like Spain or Italy, with less access to this type of measure, you will help via the TLTRO?

It is true that in some jurisdictions you do not have many corporate bonds. But as I just said: the initial effect of our purchases will spread to other assets and other markets. So there will be a reinvestment of the liquidity. Those having sold corporate bonds will rebalance by buying other things. Some people will question the need for such a measure.

They are right in saying that the situation is not dramatic, but I would stress that it is still fragile. Yes, we can see that the situation is improving, as, for example, unemployment is coming down. But we have not reached the 'escape velocity' yet where the rocket is not bound by gravity anymore.

On the TLTRO, some say it is not going to make much difference, because the problem is the demand, not the supply of credit.

As shown by our Bank Lending Survey, credit demand is picking up and you also see from actual bank credit growth that the numbers are improving. So we now give a push for these developments to proceed and maybe to accelerate.

Do not overlook the following: In the last tranches of the TLTRO I you could borrow for less and less time, as the loans had all the same maturity, that is September 2018, in an environment where the rates were falling.

This time it's different: in one year you can still borrow for four years at the conditions prevailing at that time. And, banks can benefit from a negative rate as low as our deposit facility rate if they meet the thresholds for credit growth. All this is quite bold. It will certainly facilitate cheaper funding of banks by replacing more expensive funding instruments by our TLTRO II.

Don't you think that the discussion in Germany about how harmful the accommodative stance of the ECB is lacks some analysis on some wrong business models, for example the one of the Sparkassen?

What we experience in the banking sector is difficult and we have to be very attentive to that, but it is also true that the banks have to rethink their activities fundamentally. I mention here digitalization, which is a very big challenge for the banks. It has the potential to change the business model fundamentally.

The interest rate is not a favourable factor, but it is one of the factors. And as long as you have a positive impact on the economy from negative rates, you have better growth, fewer NPLs, so we have seen positive factors for banks.

The problem for banks is not 2016, it is the medium term, if the situation becomes persistent and the business model is not adjusted, then profitability becomes a major issue.

The staff projections don’t include the impact of the new measures. What will be the impact on inflation and growth of the package?

The measures we took should bring us close to the 2 per cent target at the end of 2018. But don't forget, the measures we take like the APP are supposed to remain in place as long as inflation has not reached a sustainable adjustment in the path of inflation. It must be sustainable.

We are not yet there. In the forward guidance we said: we expect the interest rates to be low or lower for an extended period of time, and well past the horizon of our net asset purchases, which currently have an horizon to at least March 2017.

Can I ask you about what’s left in the toolbox? Could we see ‘helicopter drops’?

There has been a lot of skepticism recently about monetary policy, not only in delivering but in saying ‘your toolbox is empty’. We say, ‘no it’s not true’. There are many things you can do. The question is what is appropriate, and at what time. I think for the time being we have what we have, and it is not appropriate to discuss the next set of measures.

But in principle the ECB could print cheques and send them to people?

Yes, all central banks can do it. You can issue currency and you distribute it to people. That’s helicopter money. Helicopter money is giving to the people part of the net present value of your future seigniorage, the profit you make on the future banknotes. The question is, if and when is it opportune to make recourse to that sort of instrument which is really an extreme sort of instrument.

There are other things you can theoretically do. There are several examples in the literature. So when we say we haven’t reached the limit of the toolbox, I think that’s true.

In Germany, the biggest economy in Europe, there is a very distortive discussion about the ECB. Aren’t you worried that this discussion is very dangerous to maintain trust within the eurozone?

I think the responsibilities for the problems we have are collective. I think everyone has to look from the point of view of the other. Don’t forget, a lot of excess German savings went to Spain, to the Spanish banking system. I don’t deny that the problem in creditor countries gets worse in some respects the lower we cut the deposit rate.

It is true we are looking at this, and it is true that when we decided some recomposition of our toolbox, we took that into account. But, fundamentally, the issue is not so much the negative rates, the main issue is mistrust in the willingness of the more indebted countries to really seize this opportunity to forcefully address the problems. This is much more what drives the German view.

Italy is often accused of not doing enough to solve its structural problems. What are the changes that could really unlock growth in Italy?

The real question is ‘what drives prosperity?’ I think prosperity is linked to education, productivity, the rule of law, property rights and all these things, certainly not monetary policy. In Italy productivity really started to stop growing in the early 1990s. I think this is a fundamental reflection for the country. Some key questions like the efficiency of the judicial system, the labour market reforms, liberalizations in services, have in all or in part been tackled. But I think the agenda remains unfortunately significant. To give you just a few examples, I have been worried by the insufficient spreading of ICT technology.

Business investment is recovering everywhere, because demand is recovering so investment is following, but one of the weaker investment performances is in Italy. I think the minister of finance and the government are well aware of what the priorities are, of what needs to be done.

One thing you haven’t mentioned is fiscal policy. In Rome one often hears the argument that Italy should be allowed to expand fiscal policy more to really help the recovery. One also hears that the European fiscal rules are not fit for purpose. How do you respond to that?

Experience tells that there is always a reason to postpone fiscal savings and that fiscal policy is often procyclical.

So the only appropriate response to these experiences is having suitable fiscal rules and following them over the full cycle. Yes, there is the risk of doing the wrong things.

For example, in 2011, not necessarily mentioning Italy but focusing on the European level, consolidation was necessary. However, the composition could have been more growth friendly. Instead of raising taxes, spending could have been cut, and instead of cutting investment in infrastructure, government consumption growth could have been reduced. And particularly in the current juncture, investment should not be penalized but encouraged in countries like Italy.

Fiscal consolidation is always a lot about composition, about timing. Successful consolidation could involve pension reforms, which spread consolidation through the years. In this respect, in the past Italy went a long way to improve fiscal sustainability through its pension reform.

I know in Italy there is a discussion over a coordinated tax reduction. What I see is that fiscal policy was slightly expansionary last year and will be this year. Well-designed structural reform packages, which entail short-term costs and have a clear impact on growth potential, are taken into account by the Commission and they may affect temporarily the adjustment toward the achievement of fiscal objectives. But of course the lower fiscal adjustment has to be commensurate to the beneficial impact of reforms on the growth potential and the sustainability of public finances.

Do you think there should be a haircut on Greek debt?

If you look at the wealth improvement of Greece in terms of disposable income, before the crisis it was spectacular and then it went the other way very quickly. So it was basically on shaky grounds, a large current account deficit, it borrowed money, so at some point it corrected.

All this makes you very cautious to say we just do this or that and support the recovery in the absence of a very convincing programme of reforms. Greece was the extreme case, the demonstration that the monetary union was unprepared to deal with a financial cycle correction, especially in some countries. Fortunately, new institutions have been put in place, such as the European Stability Mechanism, the Single Supervisory Mechanism, the Single Resolution Mechanism. But we are not there yet, the banking union is not a real banking union yet.

Who is stopping the third pillar of the banking union?

It is always the same problem. All will accept it, if they can trust the other members of this mutualized system to address what they think are risks.

Do you accept the argument that one needs to find ways to limit risks in the banking sector?

Yes, but the question is how you define that. That’s where the differences are. The single deposit guarantee has rarely been called and only for very small institutions. There is plenty of bail-inable assets before you reach small deposits. This deposit guarantee for me is something which distracts. We should do it. We could take the risk of having this guarantee.

A common deposit insurance would help, but it's more important to allow a European bank to be able to operate in the euro area as a single entity.

Even this small deposit guarantee scheme is a big political problem for Germany.

I think personally you should announce an objective and a roadmap. We have a roadmap for the deposit guarantee scheme, but it is very far away. We have to spell out on paper what we consider as required conditions before you can mutualise in, for example, 5 years. That would create a new environment for banking.

But the Germans have a roadmap: they say government bonds must not be risk-free and that they want a common bankruptcy law. These are very difficult conditions.

As for sovereign debt, we have learnt from the crisis that it is not risk-free, that is clear. On the other hand, sovereign debt plays an important role in our economy, in the financial sector. So one needs a very thorough reflection on this. That’s why the sustainability of public finances is key.

That’s why one can’t just say ‘let’s lower taxes and the economy will follow and we will self-finance the tax cut’. I think one needs to be careful as sovereign debt is a key pillar of our financial system.

A final question on Brexit. Do you have any contingency plans in place at the ECB?

Brexit is part of this tendency for some to say that independent nations can do it better than collective solutions. I am confident that the voters will understand that national solutions are worse, that we have to reinforce Europe and not the opposite.

Source: ECB statement

Comentarii

Adauga un comentariu

Adauga un comentariu folosind contul de Facebook

Alte stiri din categoria: Noutati BCE

Banca Centrala Europeana (BCE) explica de ce a majorat dobanda la 2%

Banca Centrala Europeana (BCE) explica de ce a majorat dobanda la 2%, in cadrul unei conferinte de presa sustinute de Christine Lagarde, președinta BCE, si Luis de Guindos, vicepreședintele BCE. Iata textul publicat de BCE: DECLARAȚIE DE POLITICĂ MONETARĂ detalii

BCE creste dobanda la 2%, dupa ce inflatia a ajuns la 10%

Banca Centrala Europeana (BCE) a majorat dobanda de referinta pentru tarile din zona euro cu 0,75 puncte, la 2% pe an, din cauza cresterii substantiale a inflatiei, ajunsa la aproape 10% in septembrie, cu mult peste tinta BCE, de doar 2%. In aceste conditii, BCE a anuntat ca va continua sa majoreze dobanda de politica monetara. De asemenea, BCE a luat masuri pentru a reduce nivelul imprumuturilor acordate bancilor in perioada pandemiei coronavirusului, prin majorarea dobanzii aferente acestor facilitati, denumite operațiuni țintite de refinanțare pe termen mai lung (OTRTL). Comunicatul BCE Consiliul guvernatorilor a decis astăzi să majoreze cu 75 puncte de bază cele trei rate ale dobânzilor detalii

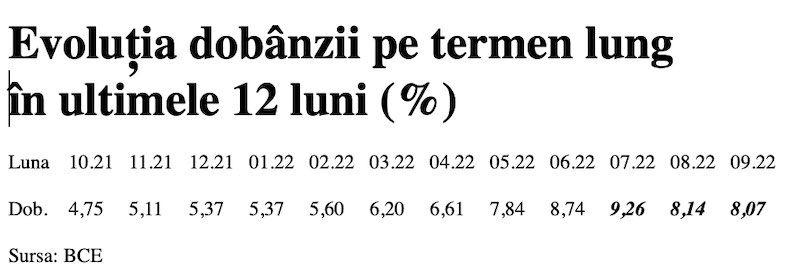

Dobânda pe termen lung a continuat să scadă in septembrie 2022. Ecartul față de Polonia și Cehia, redus semnificativ

Dobânda pe termen lung pentru România a scăzut în septembrie 2022 la valoarea medie de 8,07%, potrivit datelor publicate de Banca Centrală Europeană. Acest indicator, cu referința la un termen de 10 ani (10Y), a continuat astfel tendința detalii

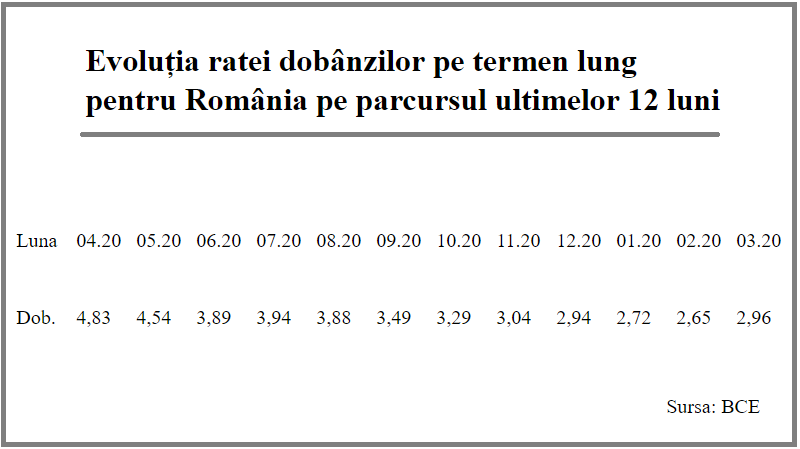

Rata dobanzii pe termen lung pentru Romania, in crestere la 2,96%

Rata dobânzii pe termen lung pentru România a crescut la 2,96% în luna martie 2021, de la 2,65% în luna precedentă, potrivit datelor publicate de Banca Centrală Europeană. Acest indicator critic pentru plățile la datoria externă scăzuse anterior timp de șapte luni detalii

- BCE recomanda bancilor sa nu plateasca dividende

- Modul de functionare a relaxarii cantitative (quantitative easing – QE)

- Dobanda la euro nu va creste pana in iunie 2020

- BCE trebuie sa fie consultata inainte de adoptarea de legi care afecteaza bancile nationale

- BCE a publicat avizul privind taxa bancara

- BCE va mentine la 0% dobanda de referinta pentru euro cel putin pana la finalul lui 2019

- ECB: Insights into the digital transformation of the retail payments ecosystem

- ECB introductory statement on Governing Council decisions

- Speech by Mario Draghi, President of the ECB: Sustaining openness in a dynamic global economy

- Deciziile de politica monetara ale BCE

Profil de Bancher

-

Florina Vizinteanu, Presedinte Directorat

BCR Asigurari de Viata Vienna Insurance Group

„Este timpul ca fiecare dintre noi să ne ... vezi profil

Criza COVID-19

- In majoritatea unitatilor BRD se poate intra fara certificat verde

- La BCR se poate intra fara certificat verde

- Firmele, obligate sa dea zile libere parintilor care stau cu copiii in timpul pandemiei de coronavirus

- CEC Bank: accesul in banca se face fara certificat verde

- Cum se amana ratele la creditele Garanti BBVA

Topuri Banci

- Topul bancilor dupa active si cota de piata in perioada 2022-2015

- Topul bancilor cu cele mai mici dobanzi la creditele de nevoi personale

- Topul bancilor la active in 2019

- Topul celor mai mari banci din Romania dupa valoarea activelor in 2018

- Topul bancilor dupa active in 2017

Asociatia Romana a Bancilor (ARB)

- Băncile din România nu au majorat comisioanele aferente operațiunilor în numerar

- Concurs de educatie financiara pentru elevi, cu premii in bani

- Creditele acordate de banci au crescut cu 14% in 2022

- Romanii stiu educatie financiara de nota 7

- Gradul de incluziune financiara in Romania a ajuns la aproape 70%

ROBOR

- ROBOR: ce este, cum se calculeaza, ce il influenteaza, explicat de Asociatia Pietelor Financiare

- ROBOR a scazut la 1,59%, dupa ce BNR a redus dobanda la 1,25%

- Dobanzile variabile la creditele noi in lei nu scad, pentru ca IRCC ramane aproape neschimbat, la 2,4%, desi ROBOR s-a micsorat cu un punct, la 2,2%

- IRCC, indicele de dobanda pentru creditele in lei ale persoanelor fizice, a scazut la 1,75%, dar nu va avea efecte imediate pe piata creditarii

- Istoricul ROBOR la 3 luni, in perioada 01.08.1995 - 31.12.2019

Taxa bancara

- Normele metodologice pentru aplicarea taxei bancare, publicate de Ministerul Finantelor

- Noul ROBOR se va aplica automat la creditele noi si prin refinantare la cele in derulare

- Taxa bancara ar putea fi redusa de la 1,2% la 0,4% la bancile mari si 0,2% la cele mici, insa bancherii avertizeaza ca indiferent de nivelul acesteia, intermedierea financiara va scadea iar dobanzile vor creste

- Raiffeisen anunta ca activitatea bancii a incetinit substantial din cauza taxei bancare; strategia va fi reevaluata, nu vor mai fi acordate credite cu dobanzi mici

- Tariceanu anunta un acord de principiu privind taxa bancara: ROBOR-ul ar putea fi inlocuit cu marja de dobanda a bancilor

Statistici BNR

- Deficitul contului curent, aproape 20 miliarde euro după primele nouă luni

- Deficitul contului curent, aproape 18 miliarde euro după primele opt luni

- Deficitul contului curent, peste 9 miliarde euro pe primele cinci luni

- Deficitul contului curent, 6,6 miliarde euro după prima treime a anului

- Deficitul contului curent pe T1, aproape 4 miliarde euro

Legislatie

- Legea nr. 311/2015 privind schemele de garantare a depozitelor şi Fondul de garantare a depozitelor bancare

- Rambursarea anticipata a unui credit, conform OUG 50/2010

- OUG nr.21 din 1992 privind protectia consumatorului, actualizata

- Legea nr. 190 din 1999 privind creditul ipotecar pentru investiții imobiliare

- Reguli privind stabilirea ratelor de referinţă ROBID şi ROBOR

Lege plafonare dobanzi credite

- BNR propune Parlamentului plafonarea dobanzilor la creditele bancilor intre 1,5 si 4 ori peste DAE medie, in functie de tipul creditului; in cazul IFN-urilor, plafonarea dobanzilor nu se justifica

- Legile privind plafonarea dobanzilor la credite si a datoriilor preluate de firmele de recuperare se discuta in Parlament (actualizat)

- Legea privind plafonarea dobanzilor la credite nu a fost inclusa pe ordinea de zi a comisiilor din Camera Deputatilor

- Senatorul Zamfir, despre plafonarea dobanzilor la credite: numai bou-i consecvent!

- Parlamentul dezbate marti legile de plafonare a dobanzilor la credite si a datoriilor cesionate de banci firmelor de recuperare (actualizat)

Anunturi banci

- Cate reclamatii primeste Intesa Sanpaolo Bank si cum le gestioneaza

- Platile instant, posibile la 13 banci

- Aplicatia CEC app va functiona doar pe telefoane cu Android minim 8 sau iOS minim 12

- Bancile comunica automat cu ANAF situatia popririlor

- BRD bate recordul la credite de consum, in ciuda dobanzilor mari, si obtine un profit ridicat

Analize economice

- România, „lanterna roșie” a cheltuielilor pentru cercetare-dezvoltare în UE

- Deficitul contului curent, peste 24 miliarde euro după primele zece luni

- Deficit comercial record în octombrie 2024

- Productivitatea în comerț, peste cea din industrie

- -6,2% din PIB, deficit bugetar după zece luni

Ministerul Finantelor

- Datoria publică, 51,4% din PIB la mijlocul anului

- Deficit bugetar de 3,6% din PIB după prima jumătate a anului

- Deficit bugetar de 3,4% din PIB după primele cinci luni ale anului

- Deficit bugetar îngrijorător după prima treime a anului

- Deficitul bugetar, -2,06% din PIB pe primul trimestru al anului

Biroul de Credit

- FUNDAMENTAREA LEGALITATII PRELUCRARII DATELOR PERSONALE IN SISTEMUL BIROULUI DE CREDIT

- BCR: prelucrarea datelor personale la Biroul de Credit

- Care banci si IFN-uri raporteaza clientii la Biroul de Credit

- Ce trebuie sa stim despre Biroul de Credit

- Care este procedura BCR de raportare a clientilor la Biroul de Credit

Procese

- ANPC pierde un proces cu Intesa si ARB privind modul de calcul al ratelor la credite

- Un client Credius obtine in justitie anularea creditului, din cauza dobanzii prea mari

- Hotararea judecatoriei prin care Aedificium, fosta Raiffeisen Banca pentru Locuinte, si statul sunt obligati sa achite unui client prima de stat

- Decizia Curtii de Apel Bucuresti in procesul dintre Raiffeisen Banca pentru Locuinte si Curtea de Conturi

- Vodafone, obligata de judecatori sa despagubeasca un abonat caruia a refuzat sa-i repare un telefon stricat sau sa-i dea banii inapoi (decizia instantei)

Stiri economice

- Inflația anuală a crescut la 5,11%, prin efect de bază

- Datoria publică, 54,4% din PIB la finele lunii septembrie 2024

- România, tot prima dar în trendul UE la inflația anuală

- Datoria publică, 52,7% din PIB la finele lunii august 2024

- -5,44% din PIB, deficit bugetar înaintea ultimului trimestru din 2024

Statistici

- România, pe locul trei în UE la creșterea costului muncii în T2 2024

- Cheltuielile cu pensiile - România, pe locul 19 în UE ca pondere în PIB

- Dobanda din Cehia a crescut cu 7 puncte intr-un singur an

- Care este valoarea salariului minim brut si net pe economie in 2024?

- Cat va fi salariul brut si net in Romania in 2024, 2025, 2026 si 2027, conform prognozei oficiale

FNGCIMM

- Programul IMM Invest continua si in 2021

- Garantiile de stat pentru credite acordate de FNGCIMM au crescut cu 185% in 2020

- Programul IMM invest se prelungeste pana in 30 iunie 2021

- Firmele pot obtine credite bancare garantate si subventionate de stat, pe baza facturilor (factoring), prin programul IMM Factor

- Programul IMM Leasing va fi operational in perioada urmatoare, anunta FNGCIMM

Calculator de credite

- ROBOR la 3 luni a scazut cu aproape un punct, dupa masurile luate de BNR; cu cat se reduce rata la credite?

- In ce mall din sectorul 4 pot face o simulare pentru o refinantare?

Noutati BCE

- Acord intre BCE si BNR pentru supravegherea bancilor

- Banca Centrala Europeana (BCE) explica de ce a majorat dobanda la 2%

- BCE creste dobanda la 2%, dupa ce inflatia a ajuns la 10%

- Dobânda pe termen lung a continuat să scadă in septembrie 2022. Ecartul față de Polonia și Cehia, redus semnificativ

- Rata dobanzii pe termen lung pentru Romania, in crestere la 2,96%

Noutati EBA

- Bancile romanesti detin cele mai multe titluri de stat din Europa

- Guidelines on legislative and non-legislative moratoria on loan repayments applied in the light of the COVID-19 crisis

- The EBA reactivates its Guidelines on legislative and non-legislative moratoria

- EBA publishes 2018 EU-wide stress test results

- EBA launches 2018 EU-wide transparency exercise

Noutati FGDB

- Banii din banci sunt garantati, anunta FGDB

- Depozitele bancare garantate de FGDB au crescut cu 13 miliarde lei

- Depozitele bancare garantate de FGDB reprezinta doua treimi din totalul depozitelor din bancile romanesti

- Peste 80% din depozitele bancare sunt garantate

- Depozitele bancare nu intra in campania electorala

CSALB

- Sistemul bancar romanesc este deosebit de bine pregatit pentru orice fel de socuri

- La CSALB poti castiga un litigiu cu banca pe care l-ai pierde in instanta

- Negocierile dintre banci si clienti la CSALB, in crestere cu 30%

- Sondaj: dobanda fixa la credite, considerata mai buna decat cea variabila, desi este mai mare

- CSALB: Romanii cu credite caută soluții pentru reducerea ratelor. Cum raspund bancile

First Bank

- Ce trebuie sa faca cei care au asigurare la credit emisa de Euroins

- First Bank este reprezentanta Eurobank in Romania: ce se intampla cu creditele Bancpost?

- Clientii First Bank pot face plati prin Google Pay

- First Bank anunta rezultatele financiare din prima jumatate a anului 2021

- First Bank are o noua aplicatie de mobile banking

Noutati FMI

- FMI: criza COVID-19 se transforma in criza economica si financiara in 2020, suntem pregatiti cu 1 trilion (o mie de miliarde) de dolari, pentru a ajuta tarile in dificultate; prioritatea sunt ajutoarele financiare pentru familiile si firmele vulnerabile

- FMI cere BNR sa intareasca politica monetara iar Guvernului sa modifice legea pensiilor

- FMI: majorarea salariilor din sectorul public si legea pensiilor ar trebui reevaluate

- IMF statement of the 2018 Article IV Mission to Romania

- Jaewoo Lee, new IMF mission chief for Romania and Bulgaria

Noutati BERD

- Creditele neperformante (npl) - statistici BERD

- BERD este ingrijorata de investigatia autoritatilor din Republica Moldova la Victoria Bank, subsidiara Bancii Transilvania

- BERD dezvaluie cat a platit pe actiunile Piraeus Bank

- ING Bank si BERD finanteaza parcul logistic CTPark Bucharest

- EBRD hails Moldova banking breakthrough

Noutati Federal Reserve

- Federal Reserve anunta noi masuri extinse pentru combaterea crizei COVID-19, care produce pagube "imense" in Statele Unite si in lume

- Federal Reserve urca dobanda la 2,25%

- Federal Reserve decided to maintain the target range for the federal funds rate at 1-1/2 to 1-3/4 percent

- Federal Reserve majoreaza dobanda de referinta pentru dolar la 1,5% - 1,75%

- Federal Reserve issues FOMC statement

Noutati BEI

- BEI a redus cu 31% sprijinul acordat Romaniei in 2018

- Romania implements SME Initiative: EUR 580 m for Romanian businesses

- European Investment Bank (EIB) is lending EUR 20 million to Agricover Credit IFN

Mobile banking

- Comisioanele BRD pentru MyBRD Mobile, MyBRD Net, My BRD SMS

- Termeni si conditii contractuale ale serviciului You BRD

- Recomandari de securitate ale BRD pentru utilizatorii de internet/mobile banking

- CEC Bank - Ghid utilizare token sub forma de card bancar

- Cinci banci permit platile cu telefonul mobil prin Google Pay

Noutati Comisia Europeana

- Avertismentul Comitetului European pentru risc sistemic (CERS) privind vulnerabilitățile din sistemul financiar al Uniunii

- Cele mai mici preturi din Europa sunt in Romania

- State aid: Commission refers Romania to Court for failure to recover illegal aid worth up to €92 million

- Comisia Europeana publica raportul privind progresele inregistrate de Romania in cadrul mecanismului de cooperare si de verificare (MCV)

- Infringements: Commission refers Greece, Ireland and Romania to the Court of Justice for not implementing anti-money laundering rules

Noutati BVB

- BET AeRO, primul indice pentru piata AeRO, la BVB

- Laptaria cu Caimac s-a listat pe piata AeRO a BVB

- Banca Transilvania plateste un dividend brut pe actiune de 0,17 lei din profitul pe 2018

- Obligatiunile Bancii Transilvania se tranzactioneaza la Bursa de Valori Bucuresti

- Obligatiunile Good Pople SA (FRU21) au debutat pe piata AeRO

Institutul National de Statistica

- Comerțul cu amănuntul - în creștere cu 8% pe primele 10 luni

- Deficitul balanței comerciale la 9 luni, cu 15% mai mare față de aceeași perioadă a anului trecut

- Producția industrială, în scădere semnificativă

- Pensia reală, în creștere cu 8,7% pe luna august 2024

- Avansul PIB pe T1 2024, majorat la +0,5%

Informatii utile asigurari

- Data de la care FGA face plati pentru asigurarile RCA Euroins: 17 mai 2023

- Asigurarea împotriva dezastrelor, valabilă și in caz de faliment

- Asiguratii nu au nevoie de documente de confirmare a cutremurului

- Cum functioneaza o asigurare de viata Metropolitan pentru un credit la Banca Transilvania?

- Care sunt documente necesare pentru dosarul de dauna la Cardif?

ING Bank

- La ING se vor putea face plati instant din decembrie 2022

- Cum evitam tentativele de frauda online?

- Clientii ING Bank trebuie sa-si actualizeze aplicatia Home Bank pana in 20 martie

- Obligatiunile Rockcastle, cel mai mare proprietar de centre comerciale din Europa Centrala si de Est, intermediata de ING Bank

- ING Bank transforma departamentul de responsabilitate sociala intr-unul de sustenabilitate

Ultimele Comentarii

-

împrumut

Vreau să apreciez pe Karin Sabine un împrumut de 9000€ pentru mine. Dacă aveți nevoie de un ... detalii

-

împrumut

Vreau să apreciez pe Karin Sabine un împrumut de 9000€ pentru mine. Dacă aveți nevoie de un ... detalii

-

Buna ziua! Am nevoie de ajutor!

Buna ziua! Am trimis activare cont si imi scrie ca au expediat QR Cod pe posta dar nu mia venit ... detalii

-

Înșelătorie

Mare atenție la firma vex group, te pune să investești 250 € în Forex, câștigi ceva și ... detalii

-

interdictie conturi ING

Buna ziua, o situatie ca cele de mai sus am patit si eu, cu diferenta ca Revolut a deblocat contul ... detalii