Jean-Claude Trichet: Interview with the Financial Times

Autor: Bancherul.ro

Autor: Bancherul.ro

2011-10-14 13:48

Interview with Jean-Claude Trichet, President of the European Central Bank, and the Financial Times,

conducted by Lionel Barber and Ralph Atkins,

on 12 October 2011 in London

Financial Times: What needs to be done to contain and bring the eurozone crisis to a close?

Jean-Claude Trichet: We have to be lucid, recognising the acuteness of the situation. Noting that there is an interplay between the sovereign risk crisis and the banking sector, and that we have to act both at a global level and at a European level. In such situations being ahead of the curve is of the essence. We have to take the right decisions in reinforcing the balance sheets of the banking sector on the one hand and, on the other hand, doing what is necessary to restore as completely as possible the credibility of the sovereign signature. Europeans have a special responsibility because they are the epicentre of these tensions which are of a global nature.

What do European leaders need to do to restore the credibility of sovereign debt, or government bonds?

European governments need to be crystal clear they are doing all they can, individually and collectively, to honour their signature. It is what the Heads said on 21 July 2011 in their communiqué: “All other euro area countries solemnly reaffirm their inflexible determination to honour fully their own individual sovereign signature and all their commitments to sustainable fiscal conditions and structural reforms. The euro area Heads of State or Government fully support this determination, as the credibility of all their sovereign signatures is a decisive element for financial stability in the euro area as a whole.” This declaration is, in my view, extremely important.

What are the risks in the discussions over Greece?

The ECB has a clear position. Governments should avoid a credit event and avoid a compulsory solution [on involving the private sector]. We ourselves, in the July 21 [eurozone leaders’] agreement, called for the appropriate enhancement of our own collateral.

So it is absolutely essential to prevent contagion from Greece?

Yes.

David Cameron in his Financial Times interview talked of having a firewall. How do governments make sure that firewall is credible and that contagion can be prevented?

They have an instrument, which is the EFSF. The appropriate way of having an appropriate firewall would be to leverage the EFSF capital, which is what is being discussed now by Treasuries.

Some believe that preventing contagion from Greece also requires a clear statement from governments that bond holders of other countries will not suffer haircuts or debt write-downs?

The Heads of State or Government have said very clearly that Greece is a special case and that, as I just quoted, as regards all other countries they reaffirm their inflexible determination to honour fully their own individual sovereign signature. I would say it was important to avoid any ambiguity in this respect.

Can you explain how you would leverage the EFSF?

There are various means to do that and I don’t want to embark into technicalities because it’s really the responsibility of the treasuries. But there are several ways to leverage the EFSF.

Do you think the ECB’s role in providing unlimited liquidity prevented an intensification of the global financial crisis and a depression in Europe?

I think the governing council of the ECB has demonstrated a capacity to be lucid in diagnosing the gravity of the situation since the start of the crisis in August 2007. So I would certainly echo what you say.

We have had two categories of monetary policy measures in this crisis. One has been the decisions on interest rates - what I would call the standard measures - which are designed to deliver price stability over the medium term and be sure that inflation expectations are solidly anchored.

On the other hand, in periods of abnormal tensions in financial markets, we have helped restored a better transmission of our monetary policy - of our interest rates - by other, non-standard measures.

The most important of our non-standard measures is full allotment at fixed rates, which we used as early as August 2007 and which is now a generalised concept. Other non-standard measures have included intervention in the covered bond market and in treasuries.

After almost 13 years of the euro we have delivered for 332 million fellow citizens 2.0 per cent average annual inflation. This is better than over the past 50 years for the main euro area countries, and we can see from information we extract from financial markets that we are credible to deliver price stability for the next 10 years, in line with our definition.

So this is a level of credibility, after four years of crisis, which demonstrates the effectiveness of our so-called separation principle between the standard measures and the non-standard measures.

As it is obvious, the euro as a currency is credible and solid. The challenges in the euro area are related to fiscal credibility and financial stability.

What needs to be done today, tomorrow and perhaps in the more distant future to make sure that the governance systems for the eurozone are actually credible and work properly?

The crisis revealed – like an X-ray picture - the weaknesses of many advanced economies - weaknesses in the US and in Japan as well as in Europe. In Europe it has revealed a big weakness in terms of governance – abnormal behaviour of individual countries and absence of effective surveillance of the policies pursued by the various countries. The ECB called a long time ago not only for a strict respect of the Stability and Growth Pact but also for a surveillance of competitive indicators and imbalances inside the euro area. This new pillar of surveillance is now part of the enhanced governance just decided by the European Parliament and Council.

Because of the hard lessons various countries have learnt during this crisis, I assume they will stick not only to the letter but also to the spirit of this new governance structure. It is of the essence.

Beyond this I think we have to reflect on a treaty change that would permit more than surveillance, with recommendations and appropriate sanctions. When recommendations are not followed and sanctions prove ineffective, European institutions should have the capacity to impose the necessary decisions on a particular country.

…and this is where your idea of a minister of finance comes in….

I said in my (Charlemagne award) speech in Aachen that, for the “day after tomorrow”, within the framework of an effective European executive branch, we could have a minister of finance with, in particular, three major responsibilities. He or she would have responsibility for surveillance of fiscal and macro-economic policies - including the capacity to impose decisions when necessary. And as far as the executive branch responsibility is concerned, the minister would be responsible for the financial sector of Europe, so that the financial sector could be decoupled from the various sovereign signatures in order to have an achieved single market of financial services, including in crisis periods. And the minister would have also the responsibility of representing Europe in international institutions, vis-à-vis the rest of the world.

Would this just be for the eurozone or for the 27 European Union countries?

The working assumption of European treaty is that at a certain moment in time, all 27 would be in the euro. But of course the possibility of imposing decisions would not apply outside the euro area - that goes without saying.

Do you think the appetite for that amount of economic integration is there now in Europe, among the new generation of leaders?

There are more reasons today for the Europeans to unite in economic, financial and monetary fields than there were at the beginning of the 1950s, at the time of the first speech of Robert Schuman. I really think that the structural transformation of the world, the formidable economic success of the emerging countries, of China, of India, of all emerging Asia, of Latin America, calls for the Europeans to unite very significantly. One of the main lessons of the crisis is precisely that Europe needs more unity. In my opinion, this is not necessarily perceived spontaneously or communicated appropriately to the public, but I think these are truths that are there. This necessity for Europe to unite is recognised more and more in the business sector, by all those who have a direct connection with the rest of the world.

I think we had, recently, several examples of European democracies where it was said it was impossible to take some difficult decisions. But after discussions and due reflection, the decision was finally taken in the direction of reinforcing European unity. We are presently experiencing history in the making in Europe. All what I know makes me think that no leader, no individual and no country will take the responsibility of going backwards. That’s the reason why I’m confident in the future of Europe. But it calls for a strong sense of direction and for hard work.

Even those countries where there are deep political reservations, deep political doubts?

I’m confident for all countries without any exception.

How do you respond to those leaders who say ‘we’re elected, we’re not going to be pushed around by markets’?

I think we are proud to live in market economies because they have proved the right way of producing wealth, and all other experiments have proved catastrophic. That said, market economies have to be disciplined. You must have rules. You cannot rely too naively on the spontaneous functioning of markets. Central banks were created when it became apparent that it was necessary from time to time to exert some discipline in the market.

Was not part of the problem leading up to the current crisis that there was almost an irrational belief in the perfect nature of markets and in, for example, efficient market theory?

Yes. In this respect I have to say that the immediate lessons drawn from the crash of the dotcom bubble were unfortunate. The idea was that financial markets were extraordinarily resilient - which was plain wrong. I must say, I never shared the view that we were in a world where there was no risk.

That being said, when the first diagnosis was made at a global level with China, India, Brazil, Russia around the table, as well as of course Japan, the US and the Europeans, we didn’t challenge the fact that a market economy was the best recipe for producing growth.

In Germany there’s a very strong belief in the market, which is why German conservatives opposed crisis measures taken by the ECB. We’ve had two resignations by Germans – Axel Weber and Jürgen Stark – from the governing council. If you’re talking about further steps towards European integration, are you in danger of losing the Germans?

First of all, I don’t know what ‘The Germans’ means, I don’t know what ‘The English’ means, I don’t know what ‘The French’ means. We are living in cultures that are very deep, very profound and very complex, obviously, and where fortunately you have a lot of different opinions.

We have a legitimate debate – in Europe as well as in the US and in Japan – about whether the central bank is doing well on this, well on that. The Governing Council of the ECB did all what was necessary to be faithful to its primary mandate and to take into account, in transmitting our decisions on interest rates, that we were in the worst crisis since 66 years, a crisis which was disrupting some markets.

Jürgen Stark has been a very close friend for 18 years. He has worked for Europe for the past 18 years. I have great esteem for Jürgen and all that he has done and is doing.

If you look back on all the years that you’ve been involved in European construction, is this the most serious crisis that you’ve had to deal with?

I was involved in many crises: the real economy crisis after the first oil shock, the sovereign risk crises of the 1980s, the crisis of the exchange rate mechanism in 1992 and 1993, the Asian crisis in particular. But what we are experiencing presently is bigger and has hit directly in at the heart of the advanced economies. So it is undoubtedly an historical event of the first magnitude, the worst financial crisis since the Second World War. It could have produced a great depression had appropriate decisions not been taken at the appropriate.

This is also the moment of maximum peril for Europe’s most important political and economic project and if this were to fail, it would have the gravest consequences for Europe, never mind the rest of the world?

All advanced economies are being X-rayed by the present crisis and revealing their skeletons and the weaknesses in their skeletons. It’s true for all of us - for Japan, for the US, for Europeans. Europe’s skeleton of Europe is weak because the institutional framework is weak.

I would confirm that is a major challenge and that it puts into question the strategy of all major advanced economies, including Europe and its institutional framework. At the same time, I could say, that it has positive aspects, now what are our major weaknesses. We had a period of benign neglect, at the global and European levels which was shared by financial markets, by the mainstream of economic analysis and by executive branches. As regards financial markets, before the crisis, for instance, Greece’s government was borrowing at the same interest rate as the German treasury!

Can we carry on with a situation where every country has to sign up to the slightest change and we can be held hostage, if you like, by a country like Slovakia?

I think that the complexity of the European decision-making process in a crisis situation that requires for major decisions 17 democratic decisions is obviously one of the weaknesses of the present institutional framework.

Are you confident that in the end will get a suitable rescue package agreed by European leaders at their meetings over the next two to three weeks?

All that I know makes me think that it is the clear will of the European governments. I would add that I see nobody taking the responsibility of a failure.

A lot of people think the ECB should be acting as lender of last resort to governments and that ultimately this crisis could only be resolved when the ECB says ‘we are the ultimate backstop’ Why is the ECB not prepared to be that ultimate backstop?

I think that the ECB has done all it could to be up to its responsibilities in exceptional circumstances. I explain tirelessly what we have been doing to those who are uneasy with some of the decisions we have taken. Keeping inflexibly our sense of direction – price stability – and being up to the challenges of the worst crisis since 66 years.

The ultimate backstop is, of course, the governments. To do anything that would let government off their own responsibilities would be a recipe for failure.

Are banks still being irresponsible when it comes to pay and bonuses?

I think we have a real problem here. It is a question of values. Our democracies do not understand some behaviour. It’s a very grave issue for all the democracies in the advanced economies.

You will be succeeded by a very experienced technocrat and somebody who’s also spent years on Europe’s construction. But he’s Italian and in some quarters, in the press and the media, this is seen as a potential problem. What is your response to that?

First, nationalities do not count. He is a very knowledgeable true European. And do not forget, he took all the decisions of the Governing Council as member of the college. Our decisions are collegiate decisions. So I have absolutely full confidence in what he will do, together with all our colleagues.

What do you plan to do after you leave the ECB on October 31?

I have not reflected yet on what I will do afterwards because I have to say that, even in the three weeks which I still have, there are a lot of things to do - 24 hours a day. I’m sure that I will read much more than I do today. I will certainly continue to meditate on the historical future of Europe and I will give more time to my four granddaughters

European Central Bank

Directorate Communications

Press and Information Division

Comentarii

Adauga un comentariu

Adauga un comentariu folosind contul de Facebook

Alte stiri din categoria: Noutati BCE

Banca Centrala Europeana (BCE) explica de ce a majorat dobanda la 2%

Banca Centrala Europeana (BCE) explica de ce a majorat dobanda la 2%, in cadrul unei conferinte de presa sustinute de Christine Lagarde, președinta BCE, si Luis de Guindos, vicepreședintele BCE. Iata textul publicat de BCE: DECLARAȚIE DE POLITICĂ MONETARĂ detalii

BCE creste dobanda la 2%, dupa ce inflatia a ajuns la 10%

Banca Centrala Europeana (BCE) a majorat dobanda de referinta pentru tarile din zona euro cu 0,75 puncte, la 2% pe an, din cauza cresterii substantiale a inflatiei, ajunsa la aproape 10% in septembrie, cu mult peste tinta BCE, de doar 2%. In aceste conditii, BCE a anuntat ca va continua sa majoreze dobanda de politica monetara. De asemenea, BCE a luat masuri pentru a reduce nivelul imprumuturilor acordate bancilor in perioada pandemiei coronavirusului, prin majorarea dobanzii aferente acestor facilitati, denumite operațiuni țintite de refinanțare pe termen mai lung (OTRTL). Comunicatul BCE Consiliul guvernatorilor a decis astăzi să majoreze cu 75 puncte de bază cele trei rate ale dobânzilor detalii

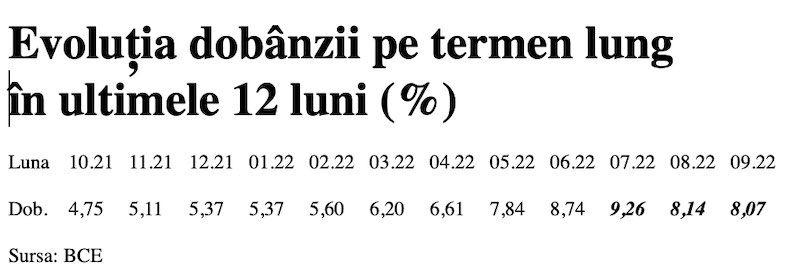

Dobânda pe termen lung a continuat să scadă in septembrie 2022. Ecartul față de Polonia și Cehia, redus semnificativ

Dobânda pe termen lung pentru România a scăzut în septembrie 2022 la valoarea medie de 8,07%, potrivit datelor publicate de Banca Centrală Europeană. Acest indicator, cu referința la un termen de 10 ani (10Y), a continuat astfel tendința detalii

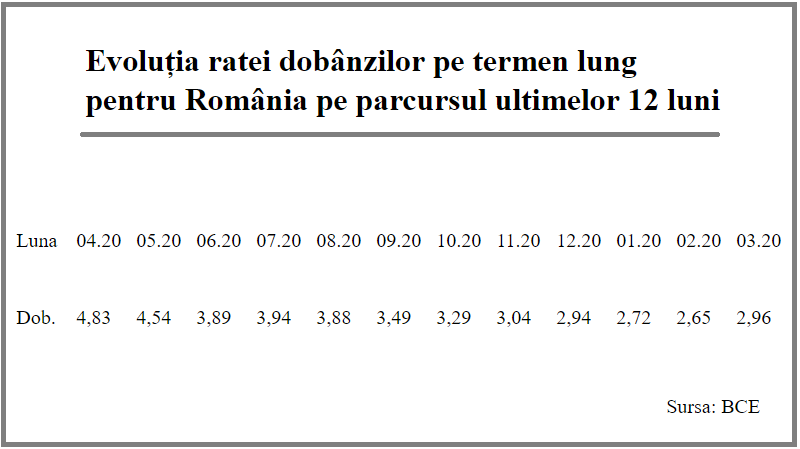

Rata dobanzii pe termen lung pentru Romania, in crestere la 2,96%

Rata dobânzii pe termen lung pentru România a crescut la 2,96% în luna martie 2021, de la 2,65% în luna precedentă, potrivit datelor publicate de Banca Centrală Europeană. Acest indicator critic pentru plățile la datoria externă scăzuse anterior timp de șapte luni detalii

- BCE recomanda bancilor sa nu plateasca dividende

- Modul de functionare a relaxarii cantitative (quantitative easing – QE)

- Dobanda la euro nu va creste pana in iunie 2020

- BCE trebuie sa fie consultata inainte de adoptarea de legi care afecteaza bancile nationale

- BCE a publicat avizul privind taxa bancara

- BCE va mentine la 0% dobanda de referinta pentru euro cel putin pana la finalul lui 2019

- ECB: Insights into the digital transformation of the retail payments ecosystem

- ECB introductory statement on Governing Council decisions

- Speech by Mario Draghi, President of the ECB: Sustaining openness in a dynamic global economy

- Deciziile de politica monetara ale BCE

Profil de Bancher

-

Carl Rossey, Vicepresedinte, Divizia Operatiuni si IT

Raiffeisen Bank

Expert in gestionarea proceselor de restructurare ... vezi profil

Criza COVID-19

- In majoritatea unitatilor BRD se poate intra fara certificat verde

- La BCR se poate intra fara certificat verde

- Firmele, obligate sa dea zile libere parintilor care stau cu copiii in timpul pandemiei de coronavirus

- CEC Bank: accesul in banca se face fara certificat verde

- Cum se amana ratele la creditele Garanti BBVA

Topuri Banci

- Topul bancilor dupa active si cota de piata in perioada 2022-2015

- Topul bancilor cu cele mai mici dobanzi la creditele de nevoi personale

- Topul bancilor la active in 2019

- Topul celor mai mari banci din Romania dupa valoarea activelor in 2018

- Topul bancilor dupa active in 2017

Asociatia Romana a Bancilor (ARB)

- Băncile din România nu au majorat comisioanele aferente operațiunilor în numerar

- Concurs de educatie financiara pentru elevi, cu premii in bani

- Creditele acordate de banci au crescut cu 14% in 2022

- Romanii stiu educatie financiara de nota 7

- Gradul de incluziune financiara in Romania a ajuns la aproape 70%

ROBOR

- ROBOR: ce este, cum se calculeaza, ce il influenteaza, explicat de Asociatia Pietelor Financiare

- ROBOR a scazut la 1,59%, dupa ce BNR a redus dobanda la 1,25%

- Dobanzile variabile la creditele noi in lei nu scad, pentru ca IRCC ramane aproape neschimbat, la 2,4%, desi ROBOR s-a micsorat cu un punct, la 2,2%

- IRCC, indicele de dobanda pentru creditele in lei ale persoanelor fizice, a scazut la 1,75%, dar nu va avea efecte imediate pe piata creditarii

- Istoricul ROBOR la 3 luni, in perioada 01.08.1995 - 31.12.2019

Taxa bancara

- Normele metodologice pentru aplicarea taxei bancare, publicate de Ministerul Finantelor

- Noul ROBOR se va aplica automat la creditele noi si prin refinantare la cele in derulare

- Taxa bancara ar putea fi redusa de la 1,2% la 0,4% la bancile mari si 0,2% la cele mici, insa bancherii avertizeaza ca indiferent de nivelul acesteia, intermedierea financiara va scadea iar dobanzile vor creste

- Raiffeisen anunta ca activitatea bancii a incetinit substantial din cauza taxei bancare; strategia va fi reevaluata, nu vor mai fi acordate credite cu dobanzi mici

- Tariceanu anunta un acord de principiu privind taxa bancara: ROBOR-ul ar putea fi inlocuit cu marja de dobanda a bancilor

Statistici BNR

- Deficitul contului curent, aproape 20 miliarde euro după primele nouă luni

- Deficitul contului curent, aproape 18 miliarde euro după primele opt luni

- Deficitul contului curent, peste 9 miliarde euro pe primele cinci luni

- Deficitul contului curent, 6,6 miliarde euro după prima treime a anului

- Deficitul contului curent pe T1, aproape 4 miliarde euro

Legislatie

- Legea nr. 311/2015 privind schemele de garantare a depozitelor şi Fondul de garantare a depozitelor bancare

- Rambursarea anticipata a unui credit, conform OUG 50/2010

- OUG nr.21 din 1992 privind protectia consumatorului, actualizata

- Legea nr. 190 din 1999 privind creditul ipotecar pentru investiții imobiliare

- Reguli privind stabilirea ratelor de referinţă ROBID şi ROBOR

Lege plafonare dobanzi credite

- BNR propune Parlamentului plafonarea dobanzilor la creditele bancilor intre 1,5 si 4 ori peste DAE medie, in functie de tipul creditului; in cazul IFN-urilor, plafonarea dobanzilor nu se justifica

- Legile privind plafonarea dobanzilor la credite si a datoriilor preluate de firmele de recuperare se discuta in Parlament (actualizat)

- Legea privind plafonarea dobanzilor la credite nu a fost inclusa pe ordinea de zi a comisiilor din Camera Deputatilor

- Senatorul Zamfir, despre plafonarea dobanzilor la credite: numai bou-i consecvent!

- Parlamentul dezbate marti legile de plafonare a dobanzilor la credite si a datoriilor cesionate de banci firmelor de recuperare (actualizat)

Anunturi banci

- Cate reclamatii primeste Intesa Sanpaolo Bank si cum le gestioneaza

- Platile instant, posibile la 13 banci

- Aplicatia CEC app va functiona doar pe telefoane cu Android minim 8 sau iOS minim 12

- Bancile comunica automat cu ANAF situatia popririlor

- BRD bate recordul la credite de consum, in ciuda dobanzilor mari, si obtine un profit ridicat

Analize economice

- Inflația anuală a crescut marginal

- Comerțul cu amănuntul - în creștere cu 7,7% cumulat pe primele 9 luni

- România, pe locul 16 din 27 de state membre ca pondere a datoriei publice în PIB

- România, tot prima în UE la inflația anuală, dar decalajul s-a redus

- Exporturile lunare în august, la cel mai redus nivel din ultimul an

Ministerul Finantelor

- Datoria publică, 51,4% din PIB la mijlocul anului

- Deficit bugetar de 3,6% din PIB după prima jumătate a anului

- Deficit bugetar de 3,4% din PIB după primele cinci luni ale anului

- Deficit bugetar îngrijorător după prima treime a anului

- Deficitul bugetar, -2,06% din PIB pe primul trimestru al anului

Biroul de Credit

- FUNDAMENTAREA LEGALITATII PRELUCRARII DATELOR PERSONALE IN SISTEMUL BIROULUI DE CREDIT

- BCR: prelucrarea datelor personale la Biroul de Credit

- Care banci si IFN-uri raporteaza clientii la Biroul de Credit

- Ce trebuie sa stim despre Biroul de Credit

- Care este procedura BCR de raportare a clientilor la Biroul de Credit

Procese

- ANPC pierde un proces cu Intesa si ARB privind modul de calcul al ratelor la credite

- Un client Credius obtine in justitie anularea creditului, din cauza dobanzii prea mari

- Hotararea judecatoriei prin care Aedificium, fosta Raiffeisen Banca pentru Locuinte, si statul sunt obligati sa achite unui client prima de stat

- Decizia Curtii de Apel Bucuresti in procesul dintre Raiffeisen Banca pentru Locuinte si Curtea de Conturi

- Vodafone, obligata de judecatori sa despagubeasca un abonat caruia a refuzat sa-i repare un telefon stricat sau sa-i dea banii inapoi (decizia instantei)

Stiri economice

- Datoria publică, 52,7% din PIB la finele lunii august 2024

- -5,44% din PIB, deficit bugetar înaintea ultimului trimestru din 2024

- Prețurile industriale - scădere în august dar indicele anual a continuat să crească

- România, pe locul 4 în UE la scăderea prețurilor agricole

- Industria prelucrătoare, evoluție neconvingătoare pe luna iulie 2024

Statistici

- România, pe locul trei în UE la creșterea costului muncii în T2 2024

- Cheltuielile cu pensiile - România, pe locul 19 în UE ca pondere în PIB

- Dobanda din Cehia a crescut cu 7 puncte intr-un singur an

- Care este valoarea salariului minim brut si net pe economie in 2024?

- Cat va fi salariul brut si net in Romania in 2024, 2025, 2026 si 2027, conform prognozei oficiale

FNGCIMM

- Programul IMM Invest continua si in 2021

- Garantiile de stat pentru credite acordate de FNGCIMM au crescut cu 185% in 2020

- Programul IMM invest se prelungeste pana in 30 iunie 2021

- Firmele pot obtine credite bancare garantate si subventionate de stat, pe baza facturilor (factoring), prin programul IMM Factor

- Programul IMM Leasing va fi operational in perioada urmatoare, anunta FNGCIMM

Calculator de credite

- ROBOR la 3 luni a scazut cu aproape un punct, dupa masurile luate de BNR; cu cat se reduce rata la credite?

- In ce mall din sectorul 4 pot face o simulare pentru o refinantare?

Noutati BCE

- Acord intre BCE si BNR pentru supravegherea bancilor

- Banca Centrala Europeana (BCE) explica de ce a majorat dobanda la 2%

- BCE creste dobanda la 2%, dupa ce inflatia a ajuns la 10%

- Dobânda pe termen lung a continuat să scadă in septembrie 2022. Ecartul față de Polonia și Cehia, redus semnificativ

- Rata dobanzii pe termen lung pentru Romania, in crestere la 2,96%

Noutati EBA

- Bancile romanesti detin cele mai multe titluri de stat din Europa

- Guidelines on legislative and non-legislative moratoria on loan repayments applied in the light of the COVID-19 crisis

- The EBA reactivates its Guidelines on legislative and non-legislative moratoria

- EBA publishes 2018 EU-wide stress test results

- EBA launches 2018 EU-wide transparency exercise

Noutati FGDB

- Banii din banci sunt garantati, anunta FGDB

- Depozitele bancare garantate de FGDB au crescut cu 13 miliarde lei

- Depozitele bancare garantate de FGDB reprezinta doua treimi din totalul depozitelor din bancile romanesti

- Peste 80% din depozitele bancare sunt garantate

- Depozitele bancare nu intra in campania electorala

CSALB

- La CSALB poti castiga un litigiu cu banca pe care l-ai pierde in instanta

- Negocierile dintre banci si clienti la CSALB, in crestere cu 30%

- Sondaj: dobanda fixa la credite, considerata mai buna decat cea variabila, desi este mai mare

- CSALB: Romanii cu credite caută soluții pentru reducerea ratelor. Cum raspund bancile

- O firma care a facut un schimb valutar gresit s-a inteles cu banca, prin intermediul CSALB

First Bank

- Ce trebuie sa faca cei care au asigurare la credit emisa de Euroins

- First Bank este reprezentanta Eurobank in Romania: ce se intampla cu creditele Bancpost?

- Clientii First Bank pot face plati prin Google Pay

- First Bank anunta rezultatele financiare din prima jumatate a anului 2021

- First Bank are o noua aplicatie de mobile banking

Noutati FMI

- FMI: criza COVID-19 se transforma in criza economica si financiara in 2020, suntem pregatiti cu 1 trilion (o mie de miliarde) de dolari, pentru a ajuta tarile in dificultate; prioritatea sunt ajutoarele financiare pentru familiile si firmele vulnerabile

- FMI cere BNR sa intareasca politica monetara iar Guvernului sa modifice legea pensiilor

- FMI: majorarea salariilor din sectorul public si legea pensiilor ar trebui reevaluate

- IMF statement of the 2018 Article IV Mission to Romania

- Jaewoo Lee, new IMF mission chief for Romania and Bulgaria

Noutati BERD

- Creditele neperformante (npl) - statistici BERD

- BERD este ingrijorata de investigatia autoritatilor din Republica Moldova la Victoria Bank, subsidiara Bancii Transilvania

- BERD dezvaluie cat a platit pe actiunile Piraeus Bank

- ING Bank si BERD finanteaza parcul logistic CTPark Bucharest

- EBRD hails Moldova banking breakthrough

Noutati Federal Reserve

- Federal Reserve anunta noi masuri extinse pentru combaterea crizei COVID-19, care produce pagube "imense" in Statele Unite si in lume

- Federal Reserve urca dobanda la 2,25%

- Federal Reserve decided to maintain the target range for the federal funds rate at 1-1/2 to 1-3/4 percent

- Federal Reserve majoreaza dobanda de referinta pentru dolar la 1,5% - 1,75%

- Federal Reserve issues FOMC statement

Noutati BEI

- BEI a redus cu 31% sprijinul acordat Romaniei in 2018

- Romania implements SME Initiative: EUR 580 m for Romanian businesses

- European Investment Bank (EIB) is lending EUR 20 million to Agricover Credit IFN

Mobile banking

- Comisioanele BRD pentru MyBRD Mobile, MyBRD Net, My BRD SMS

- Termeni si conditii contractuale ale serviciului You BRD

- Recomandari de securitate ale BRD pentru utilizatorii de internet/mobile banking

- CEC Bank - Ghid utilizare token sub forma de card bancar

- Cinci banci permit platile cu telefonul mobil prin Google Pay

Noutati Comisia Europeana

- Avertismentul Comitetului European pentru risc sistemic (CERS) privind vulnerabilitățile din sistemul financiar al Uniunii

- Cele mai mici preturi din Europa sunt in Romania

- State aid: Commission refers Romania to Court for failure to recover illegal aid worth up to €92 million

- Comisia Europeana publica raportul privind progresele inregistrate de Romania in cadrul mecanismului de cooperare si de verificare (MCV)

- Infringements: Commission refers Greece, Ireland and Romania to the Court of Justice for not implementing anti-money laundering rules

Noutati BVB

- BET AeRO, primul indice pentru piata AeRO, la BVB

- Laptaria cu Caimac s-a listat pe piata AeRO a BVB

- Banca Transilvania plateste un dividend brut pe actiune de 0,17 lei din profitul pe 2018

- Obligatiunile Bancii Transilvania se tranzactioneaza la Bursa de Valori Bucuresti

- Obligatiunile Good Pople SA (FRU21) au debutat pe piata AeRO

Institutul National de Statistica

- Deficitul balanței comerciale la 9 luni, cu 15% mai mare față de aceeași perioadă a anului trecut

- Producția industrială, în scădere semnificativă

- Pensia reală, în creștere cu 8,7% pe luna august 2024

- Avansul PIB pe T1 2024, majorat la +0,5%

- Industria prelucrătoare a trecut pe plus în aprilie 2024

Informatii utile asigurari

- Data de la care FGA face plati pentru asigurarile RCA Euroins: 17 mai 2023

- Asigurarea împotriva dezastrelor, valabilă și in caz de faliment

- Asiguratii nu au nevoie de documente de confirmare a cutremurului

- Cum functioneaza o asigurare de viata Metropolitan pentru un credit la Banca Transilvania?

- Care sunt documente necesare pentru dosarul de dauna la Cardif?

ING Bank

- La ING se vor putea face plati instant din decembrie 2022

- Cum evitam tentativele de frauda online?

- Clientii ING Bank trebuie sa-si actualizeze aplicatia Home Bank pana in 20 martie

- Obligatiunile Rockcastle, cel mai mare proprietar de centre comerciale din Europa Centrala si de Est, intermediata de ING Bank

- ING Bank transforma departamentul de responsabilitate sociala intr-unul de sustenabilitate

Ultimele Comentarii

-

LOAN OFFER

Buna ziua Aceasta pentru a informa publicul larg că oferim împrumuturi celor care au nevoie de ... detalii

-

!

Greu cu limba romana! Ce legatura are cuvantul "ecosistem" din limba romana cu sistemul de plati ... detalii

-

Bancnote vechi

Am 2 bancnote vechi:1-1000000lei;2-5000000lei Anul ... detalii

-

Bancnote vechi

Numar de ... detalii

-

Bancnote vechi

Am 3 bancnote vechi:1-1000000lei;1-5000lei;1-100000;mai multe bancnote cu eclipsa de ... detalii