Asset price bubbles: how they build up and how to prevent them?

Autor: Bancherul.ro

Autor: Bancherul.ro

2011-05-10 10:57

Speech by Gertrude Tumpel-Gugerell, Member of the Executive Board of the ECB, at alumni event of the Faculty of Economics at University of Vienna, Vienna, 3 May 2011

Ladies and Gentlemen,

It is a great pleasure for me to speak today at the University of Vienna, the alma mater from which I graduated many years ago. Many things that we have learned at the time of my studies were particularly useful in recent years. So I am happy to be back at the university and to provide you today with a policy maker’s perspective on the issue of asset price bubbles, a topic that has been rarely out of the news in the past few years. Against the background of the experience of the recent history, we now have the opportunity to reflect upon the tendency of economic systems to produce boom-bust cycles in asset prices. In my talk I want to focus on two main questions.

* Why do asset price bubbles arise and why are they so dangerous for the health and stability of the financial system?

* What can policy do about asset price bubbles?

It is not very hard to find recent examples of asset price bubbles. Chart 1 shows the evolution of real home prices in the United States and Ireland since 1990. Both economies show a sharp increase in home prices between 1995 and 2005. In Ireland prices more than tripled; in the US they rose by 70%. As we know today, these price appreciations ultimately proved unsustainable and in both countries, the housing market has fallen by a third since 2007.

Such boom-bust cycles in housing prices are by no means only a feature of the recent past. The Scandinavian economies went through a housing bubble of their own in the 1985-1995 period. As Chart 2 clearly shows, real estate prices rose and fell dramatically. In the cases illustrated in the two charts the housing bubble led subsequently to a financial crisis accompanied by a deep recession. More generally, economic historians – such as Charles Kindleberger [1] and others, have provided evidence that financial systems have a tendency to generate such financial boom-bust cycles, which sometimes take systemic dimensions that can cause or contribute to severe financial crises and recessions.

But how can we define bubbles more accurately? One way to do so is as a deviation of the value of a financial asset from its ‘correct’ or ‘fundamental’ value. Broadly speaking, the ‘fundamental’ asset price is equal to the net present value of the cash flows which the owner of the asset is entitled to receive.

Although it is easy to state in theory, this definition it is by no means easy to apply in practice for investors, regulators or central bankers. Forming forecasts of highly uncertain cash flows that stretch far into the future is a challenge, which not only requires substantial expertise but is also subject to the great uncertainty about the future values of factors influencing the asset price. For example, in 2005 – with the information available at that time – it was hard to make an unambiguously agreeable case that high US housing prices would not be confirmed by good fundamentals in the future. Although there were also warnings and some speculation on price drops. In the light of such complications, practitioners often resort to complementing fundamentals-based asset price assessments with comparing current prices with historical averages. If current prices exceed long-term averages by a sufficiently large margin, a warning signal is recorded that a bubble might be present and further analysis is triggered about whether it risks causing a crisis. I will come back to this later in my presentation.

There are many reasons why the financial system may not value assets correctly, leading to bubbles and imbalances. Investors have a tendency to look for information from the behaviour of other investors. So buying and selling ‘herds’ [2] can develop in financial markets on the basis of very little genuine news. Imperfections in credit markets [3] can lead to boom bust cycles in money and credit quantities as well as asset prices. ‘Moral hazard’ could bring about excessive risk taking by financial intermediaries who try to exploit naïve investors [4], debt-holders or the depositor safety net provided by governments [5]. Last but not least, the inherent human decision-making limitations [6] mean that actual human beings often fail to take the rational choices usually assumed in the standard academic literature.

Regardless of why asset price bubbles arise, there is little doubt that they pose potential risks for financial stability, especially when they involve bank-provided debt finance. In terms of the ECB’s framework for the analysis of systemic risk [7], asset price bubbles can contribute to the build up of financial imbalances which can unwind suddenly and cause the collapse of the banking system, with serious consequences for the real economy.

We know that asset price bubbles and financial crises can cause severe economic dislocation. This fact naturally leads to the next question I want to discuss. What can economic policy do about asset bubbles and financial imbalances?

Here it is worth drawing a distinction between what economists call ‘ex ante’ and ‘ex post’ policies. These are the economic policy equivalents to ‘prevention’ and ‘cure’ in medicine.

Once the financial system is gripped by the kind of fear and panic we saw after the collapse of Lehman Brothers in September 2008, ‘ex post’ or ‘cure’ policies are vital in order to restore confidence and prevent full-scale meltdown. This is why our actual experience during 2007-2009 was dominated by ‘ex post’ crisis management policies. This is the subject I want to turn to next.

Once the global financial crisis intensified in the autumn of 2008, the ECB did not hesitate to use the full array of policy instruments at its disposal. Interest rates were cut from 4.25% to 1% (Chart 3). The European Central Bank doubled its lending to euro area financial institutions in a matter of weeks (Chart 4). National governments took weak banks into public ownership or recapitalised them in order to restore the market’s confidence.

What we were trying to avoid was another Great Depression. The seminal analysis of Milton Friedman and Anna Schwartz [8] taught us that the Federal Reserve’s failure to reduce interest rates and provide enough liquidity to the financial system was an important amplifying factor behind the economic collapse of 1929-1933. This time we made sure we avoided a similar scenario.

Chart 5 compares the evolution of real GDP in the US during the Great Depression and during the recent financial crisis. I focus on the US because of data availability for the Great Depression period.

Between 1929 and 1933, US real output fell by more than a quarter. In contrast, between 2007 and 2009, US real GDP fell by around 5%. In the Euro area the recession was equally severe but, again, not comparable in scale to the events of 1929-1933. The Great Recession was painful but it was not a second Great Depression.

While ‘ex post’ policies are an important part of policy-makers’ toolkit, they are by no means a ‘free lunch’. Dealing with the recent financial crisis carried a substantial fiscal cost [9]. In particular, debt-to-GDP ratios have increased as a result of bank bail-outs as well as due to the effect of the economic downturn on fiscal revenues and social expenditures. For advanced economies, the IMF reports a median increase in the ratio of debt to GDP of 25 percentage points and a median direct bail-out cost of 6% of GDP. These fiscal strains are keenly felt throughout Europe at the current juncture.

The policy conclusion I want to draw from these facts is: Even when the ‘ex post’ policy response is successful at attenuating the immediate impact of a financial crisis on the real economy, the build up of public debt carries substantial costs of its own. In matters of financial stability (just as in medicine), ‘prevention’ is always better than ‘cure’.

Let me now turn to discussing ‘ex ante’ preventative policies.

The crisis revealed that our ‘ex ante preventative’ policy tools were insufficient to deal with the build up of systemic risk. Many of the post-crisis efforts by central banks, regulators and national governments have, therefore, focused on rectifying this deficiency.

An important lesson from recent crisis was that policies aimed at ensuring the stability of individual institutions (which is what micro-prudential regulation does) were not sufficient to prevent the under-pricing of risk and excessive balance sheet growth. Even though individual banks looked healthier than ever in 2007, the system as a whole was more fragile than ever.

This is why, in January 2011, the European Systemic Risk Board (ESRB) was established and charged with ensuring the integrity of the EU’s financial system. The ESRB’s main tasks are threefold: to identify and prioritise systemic risks; to issue early warnings when significant systemic risks emerge; and to issue policy recommendations for remedial action in response to the risks it identifies.

In addition, today’s globalised financial market implies that the efforts aimed at crisis prevention must have a global dimension. This is why agreeing the new Basel III capital and liquidity standards have been another important milestone in the efforts of the international central banking community to reduce systemic risk.

The Basel III standards have focused on increasing the resilience of the financial system to shocks in several important ways:

*

Higher capital and liquidity buffers

*

Increasing the quality of bank capital by focusing on loss absorbing liabilities such as common equity

*

Increasing the reliance of banks on ‘bail-in debt’ – debt instruments which convert into common equity when individual or system-wide solvency deteriorate beyond pre-specified levels.

In addition, macro-prudential regulators throughout the world are acquiring new policy tools aimed at ‘leaning against the wind’ of financial imbalances and asset price bubbles. The most important examples of such tools are the counter-cyclical capital and liquidity buffers.

These are new policy instruments and we still need to understand fully how and when we should deploy them. But one thing should be clear. Policy-makers throughout the world are determined to do all they can in order to avoid a repeat of the events of 2007-2009.

The active use of macro-prudential policy will provide a new array of ‘ex ante’ policy instruments which can lean against asset price bubbles and reduce the pro-cyclicality of the financial system.

Should monetary policy also be used to ‘lean’ against asset price bubbles and building imbalances?

The importance of monetary policy for financial bubbles and imbalances has been underscored by growing empirical evidence [10] that holding interest rates too low for too long is likely to lead to declining lending standards and growing risk-taking in the banking system. This is associated with significantly higher defaults over time.

Moreover, we have seen that the materialization of systemic risk and financial instabilities can lead to deep recessions associated with great economic costs, which in turn, carries risks for medium term price stability.

The ECB is tasked with ensuring price stability in the medium term for the citizens of the Euro area. It is unique amongst central banks in having a two pillar approach which combines both economic and monetary analysis in order to arrive at the appropriate interest rate setting.

To the extent that financial imbalances are accompanied by excessive monetary and credit growth, the ECB’s focus on medium term definitions of price stability as well as its use of the monetary pillar already provides some ‘leaning against the wind’. Work at the ECB [11] shows that the leaning against the wind attitude embedded in the ECB’s monetary analysis has contributed to containing the build-up of financial imbalances prior to the financial crisis. As a result, it has prevented a more significant fall out in economic activity during the crisis and larger risks to price stability. Therefore, this analysis shows that a cautious leaning against excessive money and credit growth and building financial imbalances as part of the monetary pillar can bring benefits not only for financial stability but also for price stability.

Let me sum up.

The historical evidence clearly shows that asset price bubbles can build up over time and, if unchecked, start to pose significant risks to systemic stability. We have been reminded that the materialization of such risks can have great economic costs, not only due to low growth and losses of income, but also in terms of heavy burdens on public finances.

So what can we learn for economic policy?

First, we have to improve the general monitoring and analysis of asset price developments and potential financial imbalances.

Second, we have to not only strengthen the micro prudential regulatory framework through better liquidity and capital provisions, but we also have to build up a strong macro prudential framework. The experiences since 2007 crisis have taught us that ensuring the stability of individual banks is not enough for the stability of the system as a whole. This is why we established the ESRB in January 2011 and tasked it with identifying and prioritising systemic risks, issuing early warnings when significant systemic risks emerge and issuing policy recommendations for remedial action.

And third, we have to make use of our monetary policy framework to come by financial imbalances that go along with excessive growth in money and credit. Our monetary policy is focused on the medium term and grants a distinct role to the analysis of monetary and credit developments. This is instrumental that the ECB is not only ensuring medium term price stability, but also contributes to the stability of the financial system.

References

Adrian, T. and Shin, H. (2011), ‘Financial Intermediaries in Monetary Economics’, Chapter 12 in The Handbook of Monetary Economics, Friedman, B. and Woodford, M. (eds.), Elsevier

Allen, F. and Gale, D. (2000), ‘Bubbles and Crises’, Economic Journal, vol. 110(460), pp. 236-55, January

Allen, F. and Gorton, G. (1993), ‘Churning Bubbles’, Review of Economic Studies, vol. 60(4), pp. 813-36, October

Aoki, K. and Nikolov, K. (2010), ‘Bubbles, Banks and Financial Stability’, University of Tokyo and ECB Mimeo

Borio, C. and Zhu, H. (2008), ‘Capital Regulation, Risk Taking and Monetary Policy: A Missing Link in the Transmission Mechanism’, BIS Working Paper No. 268

Bikhchandani, S., Hirshleifer, D. and Welch, I. (1992), ‘A Theory of Fads, Fashions, Customs and Cultural Change as Informational Cascades’, Journal of Political Economy 100, 992-1024

Christiano, L., Motto, R. and Rostagno, M. (2009), ‘Financial Factors in Economic Fluctuations’, ECB Working Paper No. 1192

ECB Financial Stability Review, December 2009, Special Feature on ‘The Concept of Systemic Risk’

Fahr, Motto, Rostagno, Smets and Tristani (2010), ‘Lessons for Monetary Policy Strategy from the Recent Past’, ECB Mimeo

Farhi, E. and Tirole, J. (2009), ‘Bubbly Liquidity’, IDEI Working Paper No. 577

Friedman, M. and Schwartz, A. (1963), A Monetary History of the United States: 1867-1960, Princeton University Press

Jimenez, G., Saurina, J., Ongena, S. and Peydro, J. (2010), ‘Credit Supply – Identifying Balance Sheet Channels using Loan Applications and Granted Loans’, ECB Working Paper No. 1179

Kindleberger, C. (1978), Manias, Panics and Crashes: A History of Financial Crisis, Wiley

Kocherlakota, N. (2009), ‘Bursting Bubbles, Consequences and Cures’, Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis Mimeo

Laeven, L. and Valencia, F. (2010), ‘Resolution of Banking Crises: the Good, the Bad and the Ugly’, IMF Working Paper 10/146

Maddaloni, A. and Peydro, J. (2011), ‘Bank Risk-Taking, Supervision and Low Interest Rates: Evidence from Euro Area and US Lending Standards’, Review of Financial Studies, Forthcoming

Martin, A. and Ventura, J. (2011), ‘A Theoretical Note on Bubbles and the Current Crisis’, IMF Economic Review, 59 (1), pp 6-40

Rogoff, K. and Reinhart, C. (2009), This Time It’s Different: Eight Centuries of Financial Folly, Princeton University Press

Thaler, R. (ed.) (1993), Advances in Behavioural Finance, Princeton University Press

Thaler, R. (ed.) (2005), Advances in Behavioural Finance Vol. II, Princeton University Press

Trichet, J.-C. (2009), ‘Systemic Risk’, Clare Distinguished Lecture in Economics and Public Policy, Clare College, Cambridge University

Welch, I. (1992), ‘Sequential Sales, Learning and Cascades’, Journal of Finance 47, pp. 695-732

Comentarii

Adauga un comentariu

Adauga un comentariu folosind contul de Facebook

Alte stiri din categoria: Noutati BCE

Banca Centrala Europeana (BCE) explica de ce a majorat dobanda la 2%

Banca Centrala Europeana (BCE) explica de ce a majorat dobanda la 2%, in cadrul unei conferinte de presa sustinute de Christine Lagarde, președinta BCE, si Luis de Guindos, vicepreședintele BCE. Iata textul publicat de BCE: DECLARAȚIE DE POLITICĂ MONETARĂ detalii

BCE creste dobanda la 2%, dupa ce inflatia a ajuns la 10%

Banca Centrala Europeana (BCE) a majorat dobanda de referinta pentru tarile din zona euro cu 0,75 puncte, la 2% pe an, din cauza cresterii substantiale a inflatiei, ajunsa la aproape 10% in septembrie, cu mult peste tinta BCE, de doar 2%. In aceste conditii, BCE a anuntat ca va continua sa majoreze dobanda de politica monetara. De asemenea, BCE a luat masuri pentru a reduce nivelul imprumuturilor acordate bancilor in perioada pandemiei coronavirusului, prin majorarea dobanzii aferente acestor facilitati, denumite operațiuni țintite de refinanțare pe termen mai lung (OTRTL). Comunicatul BCE Consiliul guvernatorilor a decis astăzi să majoreze cu 75 puncte de bază cele trei rate ale dobânzilor detalii

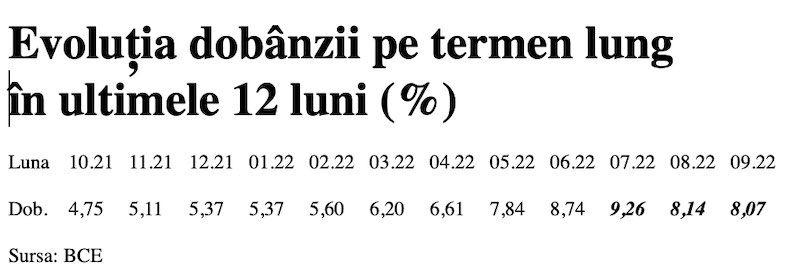

Dobânda pe termen lung a continuat să scadă in septembrie 2022. Ecartul față de Polonia și Cehia, redus semnificativ

Dobânda pe termen lung pentru România a scăzut în septembrie 2022 la valoarea medie de 8,07%, potrivit datelor publicate de Banca Centrală Europeană. Acest indicator, cu referința la un termen de 10 ani (10Y), a continuat astfel tendința detalii

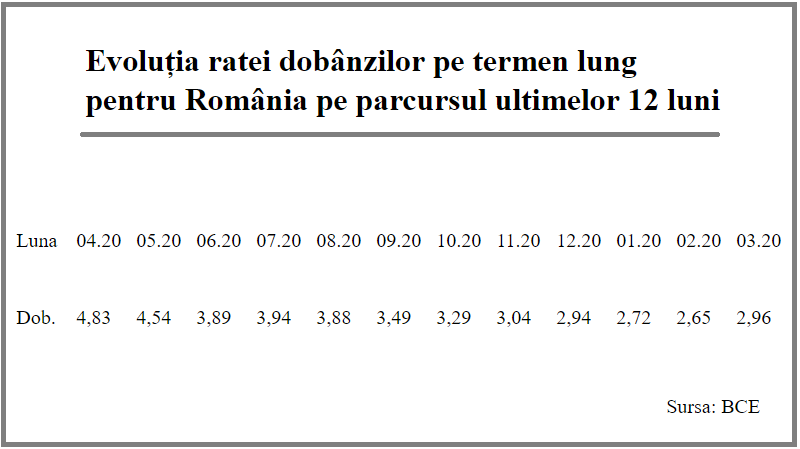

Rata dobanzii pe termen lung pentru Romania, in crestere la 2,96%

Rata dobânzii pe termen lung pentru România a crescut la 2,96% în luna martie 2021, de la 2,65% în luna precedentă, potrivit datelor publicate de Banca Centrală Europeană. Acest indicator critic pentru plățile la datoria externă scăzuse anterior timp de șapte luni detalii

- BCE recomanda bancilor sa nu plateasca dividende

- Modul de functionare a relaxarii cantitative (quantitative easing – QE)

- Dobanda la euro nu va creste pana in iunie 2020

- BCE trebuie sa fie consultata inainte de adoptarea de legi care afecteaza bancile nationale

- BCE a publicat avizul privind taxa bancara

- BCE va mentine la 0% dobanda de referinta pentru euro cel putin pana la finalul lui 2019

- ECB: Insights into the digital transformation of the retail payments ecosystem

- ECB introductory statement on Governing Council decisions

- Speech by Mario Draghi, President of the ECB: Sustaining openness in a dynamic global economy

- Deciziile de politica monetara ale BCE

Criza COVID-19

- In majoritatea unitatilor BRD se poate intra fara certificat verde

- La BCR se poate intra fara certificat verde

- Firmele, obligate sa dea zile libere parintilor care stau cu copiii in timpul pandemiei de coronavirus

- CEC Bank: accesul in banca se face fara certificat verde

- Cum se amana ratele la creditele Garanti BBVA

Topuri Banci

- Topul bancilor dupa active si cota de piata in perioada 2022-2015

- Topul bancilor cu cele mai mici dobanzi la creditele de nevoi personale

- Topul bancilor la active in 2019

- Topul celor mai mari banci din Romania dupa valoarea activelor in 2018

- Topul bancilor dupa active in 2017

Asociatia Romana a Bancilor (ARB)

- Băncile din România nu au majorat comisioanele aferente operațiunilor în numerar

- Concurs de educatie financiara pentru elevi, cu premii in bani

- Creditele acordate de banci au crescut cu 14% in 2022

- Romanii stiu educatie financiara de nota 7

- Gradul de incluziune financiara in Romania a ajuns la aproape 70%

ROBOR

- ROBOR: ce este, cum se calculeaza, ce il influenteaza, explicat de Asociatia Pietelor Financiare

- ROBOR a scazut la 1,59%, dupa ce BNR a redus dobanda la 1,25%

- Dobanzile variabile la creditele noi in lei nu scad, pentru ca IRCC ramane aproape neschimbat, la 2,4%, desi ROBOR s-a micsorat cu un punct, la 2,2%

- IRCC, indicele de dobanda pentru creditele in lei ale persoanelor fizice, a scazut la 1,75%, dar nu va avea efecte imediate pe piata creditarii

- Istoricul ROBOR la 3 luni, in perioada 01.08.1995 - 31.12.2019

Taxa bancara

- Normele metodologice pentru aplicarea taxei bancare, publicate de Ministerul Finantelor

- Noul ROBOR se va aplica automat la creditele noi si prin refinantare la cele in derulare

- Taxa bancara ar putea fi redusa de la 1,2% la 0,4% la bancile mari si 0,2% la cele mici, insa bancherii avertizeaza ca indiferent de nivelul acesteia, intermedierea financiara va scadea iar dobanzile vor creste

- Raiffeisen anunta ca activitatea bancii a incetinit substantial din cauza taxei bancare; strategia va fi reevaluata, nu vor mai fi acordate credite cu dobanzi mici

- Tariceanu anunta un acord de principiu privind taxa bancara: ROBOR-ul ar putea fi inlocuit cu marja de dobanda a bancilor

Statistici BNR

- Deficitul contului curent, aproape 20 miliarde euro după primele nouă luni

- Deficitul contului curent, aproape 18 miliarde euro după primele opt luni

- Deficitul contului curent, peste 9 miliarde euro pe primele cinci luni

- Deficitul contului curent, 6,6 miliarde euro după prima treime a anului

- Deficitul contului curent pe T1, aproape 4 miliarde euro

Legislatie

- Legea nr. 311/2015 privind schemele de garantare a depozitelor şi Fondul de garantare a depozitelor bancare

- Rambursarea anticipata a unui credit, conform OUG 50/2010

- OUG nr.21 din 1992 privind protectia consumatorului, actualizata

- Legea nr. 190 din 1999 privind creditul ipotecar pentru investiții imobiliare

- Reguli privind stabilirea ratelor de referinţă ROBID şi ROBOR

Lege plafonare dobanzi credite

- BNR propune Parlamentului plafonarea dobanzilor la creditele bancilor intre 1,5 si 4 ori peste DAE medie, in functie de tipul creditului; in cazul IFN-urilor, plafonarea dobanzilor nu se justifica

- Legile privind plafonarea dobanzilor la credite si a datoriilor preluate de firmele de recuperare se discuta in Parlament (actualizat)

- Legea privind plafonarea dobanzilor la credite nu a fost inclusa pe ordinea de zi a comisiilor din Camera Deputatilor

- Senatorul Zamfir, despre plafonarea dobanzilor la credite: numai bou-i consecvent!

- Parlamentul dezbate marti legile de plafonare a dobanzilor la credite si a datoriilor cesionate de banci firmelor de recuperare (actualizat)

Anunturi banci

- Cate reclamatii primeste Intesa Sanpaolo Bank si cum le gestioneaza

- Platile instant, posibile la 13 banci

- Aplicatia CEC app va functiona doar pe telefoane cu Android minim 8 sau iOS minim 12

- Bancile comunica automat cu ANAF situatia popririlor

- BRD bate recordul la credite de consum, in ciuda dobanzilor mari, si obtine un profit ridicat

Analize economice

- Inflația anuală a crescut marginal

- Comerțul cu amănuntul - în creștere cu 7,7% cumulat pe primele 9 luni

- România, pe locul 16 din 27 de state membre ca pondere a datoriei publice în PIB

- România, tot prima în UE la inflația anuală, dar decalajul s-a redus

- Exporturile lunare în august, la cel mai redus nivel din ultimul an

Ministerul Finantelor

- Datoria publică, 51,4% din PIB la mijlocul anului

- Deficit bugetar de 3,6% din PIB după prima jumătate a anului

- Deficit bugetar de 3,4% din PIB după primele cinci luni ale anului

- Deficit bugetar îngrijorător după prima treime a anului

- Deficitul bugetar, -2,06% din PIB pe primul trimestru al anului

Biroul de Credit

- FUNDAMENTAREA LEGALITATII PRELUCRARII DATELOR PERSONALE IN SISTEMUL BIROULUI DE CREDIT

- BCR: prelucrarea datelor personale la Biroul de Credit

- Care banci si IFN-uri raporteaza clientii la Biroul de Credit

- Ce trebuie sa stim despre Biroul de Credit

- Care este procedura BCR de raportare a clientilor la Biroul de Credit

Procese

- ANPC pierde un proces cu Intesa si ARB privind modul de calcul al ratelor la credite

- Un client Credius obtine in justitie anularea creditului, din cauza dobanzii prea mari

- Hotararea judecatoriei prin care Aedificium, fosta Raiffeisen Banca pentru Locuinte, si statul sunt obligati sa achite unui client prima de stat

- Decizia Curtii de Apel Bucuresti in procesul dintre Raiffeisen Banca pentru Locuinte si Curtea de Conturi

- Vodafone, obligata de judecatori sa despagubeasca un abonat caruia a refuzat sa-i repare un telefon stricat sau sa-i dea banii inapoi (decizia instantei)

Stiri economice

- Datoria publică, 52,7% din PIB la finele lunii august 2024

- -5,44% din PIB, deficit bugetar înaintea ultimului trimestru din 2024

- Prețurile industriale - scădere în august dar indicele anual a continuat să crească

- România, pe locul 4 în UE la scăderea prețurilor agricole

- Industria prelucrătoare, evoluție neconvingătoare pe luna iulie 2024

Statistici

- România, pe locul trei în UE la creșterea costului muncii în T2 2024

- Cheltuielile cu pensiile - România, pe locul 19 în UE ca pondere în PIB

- Dobanda din Cehia a crescut cu 7 puncte intr-un singur an

- Care este valoarea salariului minim brut si net pe economie in 2024?

- Cat va fi salariul brut si net in Romania in 2024, 2025, 2026 si 2027, conform prognozei oficiale

FNGCIMM

- Programul IMM Invest continua si in 2021

- Garantiile de stat pentru credite acordate de FNGCIMM au crescut cu 185% in 2020

- Programul IMM invest se prelungeste pana in 30 iunie 2021

- Firmele pot obtine credite bancare garantate si subventionate de stat, pe baza facturilor (factoring), prin programul IMM Factor

- Programul IMM Leasing va fi operational in perioada urmatoare, anunta FNGCIMM

Calculator de credite

- ROBOR la 3 luni a scazut cu aproape un punct, dupa masurile luate de BNR; cu cat se reduce rata la credite?

- In ce mall din sectorul 4 pot face o simulare pentru o refinantare?

Noutati BCE

- Acord intre BCE si BNR pentru supravegherea bancilor

- Banca Centrala Europeana (BCE) explica de ce a majorat dobanda la 2%

- BCE creste dobanda la 2%, dupa ce inflatia a ajuns la 10%

- Dobânda pe termen lung a continuat să scadă in septembrie 2022. Ecartul față de Polonia și Cehia, redus semnificativ

- Rata dobanzii pe termen lung pentru Romania, in crestere la 2,96%

Noutati EBA

- Bancile romanesti detin cele mai multe titluri de stat din Europa

- Guidelines on legislative and non-legislative moratoria on loan repayments applied in the light of the COVID-19 crisis

- The EBA reactivates its Guidelines on legislative and non-legislative moratoria

- EBA publishes 2018 EU-wide stress test results

- EBA launches 2018 EU-wide transparency exercise

Noutati FGDB

- Banii din banci sunt garantati, anunta FGDB

- Depozitele bancare garantate de FGDB au crescut cu 13 miliarde lei

- Depozitele bancare garantate de FGDB reprezinta doua treimi din totalul depozitelor din bancile romanesti

- Peste 80% din depozitele bancare sunt garantate

- Depozitele bancare nu intra in campania electorala

CSALB

- La CSALB poti castiga un litigiu cu banca pe care l-ai pierde in instanta

- Negocierile dintre banci si clienti la CSALB, in crestere cu 30%

- Sondaj: dobanda fixa la credite, considerata mai buna decat cea variabila, desi este mai mare

- CSALB: Romanii cu credite caută soluții pentru reducerea ratelor. Cum raspund bancile

- O firma care a facut un schimb valutar gresit s-a inteles cu banca, prin intermediul CSALB

First Bank

- Ce trebuie sa faca cei care au asigurare la credit emisa de Euroins

- First Bank este reprezentanta Eurobank in Romania: ce se intampla cu creditele Bancpost?

- Clientii First Bank pot face plati prin Google Pay

- First Bank anunta rezultatele financiare din prima jumatate a anului 2021

- First Bank are o noua aplicatie de mobile banking

Noutati FMI

- FMI: criza COVID-19 se transforma in criza economica si financiara in 2020, suntem pregatiti cu 1 trilion (o mie de miliarde) de dolari, pentru a ajuta tarile in dificultate; prioritatea sunt ajutoarele financiare pentru familiile si firmele vulnerabile

- FMI cere BNR sa intareasca politica monetara iar Guvernului sa modifice legea pensiilor

- FMI: majorarea salariilor din sectorul public si legea pensiilor ar trebui reevaluate

- IMF statement of the 2018 Article IV Mission to Romania

- Jaewoo Lee, new IMF mission chief for Romania and Bulgaria

Noutati BERD

- Creditele neperformante (npl) - statistici BERD

- BERD este ingrijorata de investigatia autoritatilor din Republica Moldova la Victoria Bank, subsidiara Bancii Transilvania

- BERD dezvaluie cat a platit pe actiunile Piraeus Bank

- ING Bank si BERD finanteaza parcul logistic CTPark Bucharest

- EBRD hails Moldova banking breakthrough

Noutati Federal Reserve

- Federal Reserve anunta noi masuri extinse pentru combaterea crizei COVID-19, care produce pagube "imense" in Statele Unite si in lume

- Federal Reserve urca dobanda la 2,25%

- Federal Reserve decided to maintain the target range for the federal funds rate at 1-1/2 to 1-3/4 percent

- Federal Reserve majoreaza dobanda de referinta pentru dolar la 1,5% - 1,75%

- Federal Reserve issues FOMC statement

Noutati BEI

- BEI a redus cu 31% sprijinul acordat Romaniei in 2018

- Romania implements SME Initiative: EUR 580 m for Romanian businesses

- European Investment Bank (EIB) is lending EUR 20 million to Agricover Credit IFN

Mobile banking

- Comisioanele BRD pentru MyBRD Mobile, MyBRD Net, My BRD SMS

- Termeni si conditii contractuale ale serviciului You BRD

- Recomandari de securitate ale BRD pentru utilizatorii de internet/mobile banking

- CEC Bank - Ghid utilizare token sub forma de card bancar

- Cinci banci permit platile cu telefonul mobil prin Google Pay

Noutati Comisia Europeana

- Avertismentul Comitetului European pentru risc sistemic (CERS) privind vulnerabilitățile din sistemul financiar al Uniunii

- Cele mai mici preturi din Europa sunt in Romania

- State aid: Commission refers Romania to Court for failure to recover illegal aid worth up to €92 million

- Comisia Europeana publica raportul privind progresele inregistrate de Romania in cadrul mecanismului de cooperare si de verificare (MCV)

- Infringements: Commission refers Greece, Ireland and Romania to the Court of Justice for not implementing anti-money laundering rules

Noutati BVB

- BET AeRO, primul indice pentru piata AeRO, la BVB

- Laptaria cu Caimac s-a listat pe piata AeRO a BVB

- Banca Transilvania plateste un dividend brut pe actiune de 0,17 lei din profitul pe 2018

- Obligatiunile Bancii Transilvania se tranzactioneaza la Bursa de Valori Bucuresti

- Obligatiunile Good Pople SA (FRU21) au debutat pe piata AeRO

Institutul National de Statistica

- Deficitul balanței comerciale la 9 luni, cu 15% mai mare față de aceeași perioadă a anului trecut

- Producția industrială, în scădere semnificativă

- Pensia reală, în creștere cu 8,7% pe luna august 2024

- Avansul PIB pe T1 2024, majorat la +0,5%

- Industria prelucrătoare a trecut pe plus în aprilie 2024

Informatii utile asigurari

- Data de la care FGA face plati pentru asigurarile RCA Euroins: 17 mai 2023

- Asigurarea împotriva dezastrelor, valabilă și in caz de faliment

- Asiguratii nu au nevoie de documente de confirmare a cutremurului

- Cum functioneaza o asigurare de viata Metropolitan pentru un credit la Banca Transilvania?

- Care sunt documente necesare pentru dosarul de dauna la Cardif?

ING Bank

- La ING se vor putea face plati instant din decembrie 2022

- Cum evitam tentativele de frauda online?

- Clientii ING Bank trebuie sa-si actualizeze aplicatia Home Bank pana in 20 martie

- Obligatiunile Rockcastle, cel mai mare proprietar de centre comerciale din Europa Centrala si de Est, intermediata de ING Bank

- ING Bank transforma departamentul de responsabilitate sociala intr-unul de sustenabilitate

Ultimele Comentarii

-

LOAN OFFER

Buna ziua Aceasta pentru a informa publicul larg că oferim împrumuturi celor care au nevoie de ... detalii

-

!

Greu cu limba romana! Ce legatura are cuvantul "ecosistem" din limba romana cu sistemul de plati ... detalii

-

Bancnote vechi

Am 2 bancnote vechi:1-1000000lei;2-5000000lei Anul ... detalii

-

Bancnote vechi

Numar de ... detalii

-

Bancnote vechi

Am 3 bancnote vechi:1-1000000lei;1-5000lei;1-100000;mai multe bancnote cu eclipsa de ... detalii