Mario Draghi, President of the ECB: statement to the press conference with the transcript of the questions and answers

Introductory statement to the press conference (with Q&A)

Mario Draghi, President of the ECB,

Frankfurt am Main, 7 August 2014

Ladies and gentlemen, the Vice-President and I are very pleased to welcome you to our press conference. We will now report on the outcome of today’s meeting of the Governing Council.

Based on our regular economic and monetary analyses, we decided to keep the key ECB interest rates unchanged. The available information remains consistent with our assessment of a continued moderate and uneven recovery of the euro area economy, with low rates of inflation and subdued monetary and credit dynamics. At the same time, inflation expectations for the euro area over the medium to long term continue to be firmly anchored in line with our aim of maintaining inflation rates below, but close to, 2%. The monetary policy measures decided in early June have led to an easing of the monetary policy stance. This is in line with our forward guidance and adequately reflects the outlook for the euro area economy, as well as the differences in terms of the monetary policy cycle between major advanced economies. The targeted longer-term refinancing operations (TLTROs) that are to take place over the coming months will enhance our accommodative monetary policy stance. These operations will provide long-term funding at attractive terms and conditions over a period of up to four years for all banks that meet certain benchmarks applicable to their lending to the real economy. This should help to ease funding conditions further and stimulate credit provision to the real economy. As our measures work their way through to the economy they will contribute to a return of inflation rates to levels closer to 2%.

As stated previously, and as a follow-up to our decision in early June, we have intensified preparatory work related to outright purchases in the asset-backed securities market to enhance the functioning of the monetary policy transmission mechanism.

Looking ahead, we will maintain a high degree of monetary accommodation. Concerning our forward guidance, the key ECB interest rates will remain at present levels for an extended period of time in view of the current outlook for inflation. Moreover, the Governing Council is unanimous in its commitment to also using unconventional instruments within its mandate, should it become necessary to further address risks of too prolonged a period of low inflation. We are strongly determined to safeguard the firm anchoring of inflation expectations over the medium to long term.

Let me now explain our assessment in greater detail, starting with the economic analysis. In the first quarter of this year euro area real GDP rose by 0.2%, quarter on quarter. With regard to the second quarter, monthly indicators have been somewhat volatile, partly reflecting technical factors. Overall, recent information, including survey data available for July, remains consistent with our expectation of a continued moderate and uneven recovery of the euro area economy. Looking ahead, domestic demand should be supported by a number of factors, including the accommodative monetary policy stance and the ongoing improvements in financial conditions. In addition, the progress made in fiscal consolidation and structural reforms, as well as gains in real disposable income, should make a positive contribution to economic growth. Furthermore, demand for exports should benefit from the ongoing global recovery. However, although labour markets have shown some further signs of improvement, unemployment remains high in the euro area and, overall, unutilised capacity continues to be sizeable. Moreover, the annual rate of change of MFI loans to the private sector remained negative in June and the necessary balance sheet adjustments in the public and private sectors are likely to continue to dampen the pace of the economic recovery.

The risks surrounding the economic outlook for the euro area remain on the downside. In particular, heightened geopolitical risks, as well as developments in emerging market economies and global financial markets, may have the potential to affect economic conditions negatively, including through effects on energy prices and global demand for euro area products. A further downside risk relates to insufficient structural reforms in euro area countries, as well as weaker than expected domestic demand.

According to Eurostat’s flash estimate, euro area annual HICP inflation was 0.4% in July 2014, after 0.5% in June. This reflects primarily lower energy price inflation, while the other main components of the HICP remained broadly unchanged . On the basis of current information, annual HICP inflation is expected to remain at low levels over the coming months, before increasing gradually during 2015 and 2016. Meanwhile, inflation expectations for the euro area over the medium to long term continue to be firmly anchored in line with our aim of maintaining inflation rates below, but close to, 2%.

The Governing Council sees both upside and downside risks to the outlook for price developments as limited and broadly balanced over the medium term. In this context, we will closely monitor the possible repercussions of heightened geopolitical risks and exchange rate developments.

Turning to the monetary analysis, data for June 2014 continue to point to subdued underlying growth in broad money (M3), with annual growth standing at 1.5% in June, compared with 1.0% in May. The growth of the narrow monetary aggregate M1 stood at 5.3% in June, up from 5.0% in May. The increase in the MFI net external asset position, reflecting in part the continued interest of international investors in euro area assets, remained an important factor supporting annual M3 growth.

The annual rate of change of loans to non-financial corporations (adjusted for loan sales and securitisation) remained negative at -2.3% in June, compared with -2.5% in May and ‑3.2% in February. Lending to non-financial corporations continues to be weak, reflecting the lagged relationship with the business cycle, credit risk, credit supply factors and the ongoing adjustment of financial and non-financial sector balance sheets. At the same time, in terms of monthly flows, loans to non-financial corporations have shown some signs of a stabilisation over recent months, after recording sizeable negative monthly flows earlier in the year. This is consistent with the results of the bank lending survey for the second quarter of 2014 in which banks reported that credit standards for loans to enterprises had eased in net terms. However, they remain rather tight overall, when seen from a historical perspective. In addition, banks reported an improvement in net loan demand by non-financial corporations and households. The annual growth rate of loans to households (adjusted for loan sales and securitisation) was 0.5% in June, broadly unchanged since the beginning of 2013.

Against the background of weak credit growth, the ECB’s ongoing comprehensive assessment of banks’ balance sheets is of key importance. Banks should take full advantage of this exercise to improve their capital position, thereby supporting the scope for credit expansion during the next stages of the recovery.

To sum up, the economic analysis indicates that the current low level of inflation should be followed by a gradual upward movement in HICP inflation rates towards levels closer to 2%. A cross-check with the signals from the monetary analysis confirms this picture.

As regards fiscal policies, comprehensive fiscal consolidation in recent years has contributed to reducing budgetary imbalances. Important structural reforms have increased competitiveness and the adjustment capacity of countries’ labour and product markets. These efforts now need to gain momentum to enhance the euro area’s growth potential. Structural reforms should focus on fostering private investment and job creation. To restore sound public finances, euro area countries should proceed in line with the Stability and Growth Pact and should not unravel the progress made with fiscal consolidation. Fiscal consolidation should be designed in a growth-friendly way. A full and consistent implementation of the euro area’s existing fiscal and macroeconomic surveillance framework is key to bringing down high public debt ratios, to raising potential growth and to increasing the euro area’s resilience to shocks.

We are now at your disposal for questions.

* * *

Question: You were saying that the TLTROs would enhance our monetary policy stance. What do you exactly mean by that? And my second question is whether there is downside risk to your economic scenario having intensified, looking at the situation in Russia and the Ukraine?

Draghi: Indeed, the TLTROs will enhance our monetary policy stance in a sense because they implement a significant expansion in credit. They’re not really like the LTROs emergency funding. But these TLTROs are funding, they are to be used to lend to the real economy, to the non-financial companies, and especially to the SMEs.

We do expect a sizeable take-up. During the last press conference I think I mentioned an upper ceiling. Now, market estimates and indications by individual banks would seem to say that, overall – so not only in the first two tranches, but also in the periodic operations – a take-up between €450 billion and €850 billion should materialise. On the other hand, it’s quite understandable because these are funds that are at pretty long-term maturity with very, very attractive financial conditions.

Also, let me add that the indications coming from the bank lending survey that, as I just said, show a gradual—show actually I think for the first time a pickup in demand for loans and a gradual lessening of tightness on the supply side, would seem to indicate that these TLTROs will actually happen at the right time when there is demand for them.

So in this sense they are, not only enhancing our monetary policy stance, but they actually would give confirmation to our forward guidance.

The second question related to geopolitical risks. Well, there is no doubt that if you look at the world today, you see the geopolitical risks have increased all over the world. We have the Russian-Ukrainian crisis, Iraq, Gaza, Syria, Libya. So geopolitical risks are heightened, are higher than they were a few months ago. And some of them, like the situation in Ukraine and Russia, will have a greater impact on the euro area than they have on other parts of the world.

Now, it’s hard to assess this impact at the beginning of these crises. If one looks at the figures for trade or financial flows, they would, by and large, reveal a picture of very limited interconnections. Even as we go and look at the main financial institutions, one would count less than a handful of names of financial institutions that are especially exposed to Russia.

However, it’s very hard to assess what the actual impact is going to be when sanctions on one side and counter-sanctions on the other side are going to be undertaken. And it’s today or yesterday that we had the news that the Russian government has taken counter-sanctions, in terms of prohibition to import certain products, the threat of a prohibition to fly over certain parts of Russia, and so on. So our risks to the recovery were on the downside to begin with, and certainly one of these risks would be geopolitical developments.

Question: Going back to the heightened geopolitical risk that you have mentioned so far, in case one of those risks were to materialise and deliver a substantial shock to the euro area and a change in the outlook for inflation, how would you be ready to react? I’m thinking, of course, broad-based asset purchases. But also, what do you have in mind in this case? And talking about the ABS purchase plan, you’ve often said that this is not something that the ECB can do alone – there are many actors, many institutions in Brussels and in Basel who are looking after that. But what can the ECB do on its own if it needs to act on a relatively short timeframe?

Draghi: On the first question, I would say we’re just at the beginning. We’re still assessing what possible likely impact sanctions might have on the euro area economy. We see risk especially coming from the price of energy. But, as I said, it’s kind of difficult now to precisely define what are the options in the future, especially if the conflict were the escalate.

Our monetary policy stance remains, and will remain, accommodative, and I can only reaffirm that the Governing Council is unanimous in its commitment to also use unconventional measures, like ABS purchases, like QE, if our medium-term outlook for inflation were to change.

On the ABS, you’re right. I said that the ABS final action will depend on the action of many other actors. First of all, we have intensified preparations on the ABS, the various committees of the ECB have worked, and are working, on that. And in the last press conference I kind of listed all the areas that need work.

I would only add that we are proceedings with our work regardless of what the timing is for possible regulatory changes in this area.

And the other news is that we are about to hire – I can’t disclose any names, because the thing isn’t finished yet – but we are about to hire a consultant who will help us to design this programme in the best possible fashion.

Question: When you talk about being unanimous to do more if the medium-term outlook is too low for inflation, we’ve now got inflation at 0.4%, can you just explain why that isn’t already too low? Why that isn’t already something that should be triggering a response from the ECB? And just to get back on the ABS question, you gave some more details about the preparatory work, can you give us a sense, will this actually lead to ABS purchases? Or is this something that you will be talking about, consulting about, and may not actually lead to the ECB buying any of these things? Or are you confident that this will actually result in an ABS purchase programme? And do you have any better sense when that might be?

Draghi: The second question is, in a sense, either strange or easy to answer. If we were to work on things that don’t happen, we wouldn’t spend our time well. So the work we are doing is with the expectation that we will take action in this field. Let me add that a final decision hasn’t been taken yet. So the final decision is to stand ready with a programme that would help to strengthen our accommodative monetary policy stance, injecting money into the real economy.

And in so doing, it would lead to a reconstruction of a market that has disappeared with the crisis, also for good reasons. That’s why we are focusing our efforts on a market which would trade products that are, as I said on other occasions, simple, transparent and real. Simple, transparent and real. Simple means readable. Transparent means that you can actually go through and price them well. And real means that they are not going to be a sausage full of derivatives, as said in a somewhat more popular language.

On the other thing: isn’t 0.4% low enough? Well, it didn’t really come as a surprise because, as I told you a moment ago, this data is mostly due to the changes in the price of energy. And if we consider the HICP, excluding food and energy, we would have 0.8%, unchanged from the previous month. But having said that, there is no doubt that inflation is low and will remain low.

Inflation expectations, however, over the medium to long term, remain firmly anchored. In the short term, we observed a decline in inflation expectations because, as is quite natural, they are heavily determined on the basis of current inflation.

On a specific point that was raised by a usually accurate market observer, also if we look at five-year inflation expectations, derived from the break-even of the linkers, we would observe a 0.5% inflation expectation. This was a quite interesting point, but at least we think the calculations should be done differently. We should observe, not one issue, but the overall, the universe of issuances of linkers with that maturity. And this would show that the expectations over the five-year horizon are still anchored at 1%.

So we haven’t observed any decline on the medium- to long-term expectations. Long-term expectations remain anchored at 2%. Other expectations remain anchored at the previous levels. Short-term expectations, indeed, have declined.

Question: You ascribed some of the weaknesses in the second quarter to technical factors. And more generally, you largely left the economic assessment unchanged compared to the previous months, apart from adding the word ‘uneven’. So does that mean that you don’t see any slowing of the underlying momentum? Can you just give us a bit more detailed assessment of how you view developments there?

My second question is on inflation. The ECB staff forecasts have been persistently too optimistic on the inflation outlook. What considerations have you given to reassessing how these forecasts are being made, to get them more accurate in the future? And perhaps related to that, how big are the risks that we will see another downgrade of ECB staff inflation forecasts in September?

Draghi: On the first point, let me say that the assessment of the present situation is especially volatile because, especially over the last 2-3 months, we’ve had some positive signs. First of all, we had a disconnect, which actually has been going on for more than 2 or 3 months between soft data and hard data, with the soft data being better than the hard data, on average.

Second, we had, even amongst the soft data, we had some positive and some negatives. We had positive signs from PMI, the retail sales, the unused capacity, which is slightly less than it was, the labour market showing some improvement. And this is not soft, but it’s actually hard data. And at the same time, we had not good figures for GDP, and also on the soft side for IFO and other indicators.

You’re right in saying that the weak GDP figure depends also on technical factors, like the lower number of working days in the period that’s being observed. But having said that, I would simply repeat a sentence that you’ve heard many, many times. The recovery remains weak, fragile and uneven. And if one was really to try to detect a sign in the data that have shown up in the last 2-3 months, one would say that there has been a slowing down in the growth momentum. And this is for the weak part.

For the recovery being fragile, we just discussed the potential sources of fragility. But the unevenness part has actually become more interesting as we proceed along this modest recovery. It’s pretty clear that the countries that have undertaken a convincing programme of structural reforms are performing better – much better – than the countries that have not done so, or have done so to a limited extent. This is coming out quite clearly on the scene in front of ones eyes. That’s, I think, the broad assessment I would give for growth.

On inflation, we’ve just discussed it before. On money and credit, I think there we see that money and credit dynamics remain weak, but there are better signs, or shall I say, signs that are less bad than we were used to observe in the past.

And they come essentially from two sources: from the figures on money, and loans to non-financial corporations. As I’ve mentioned before, you see that the deterioration in lending is gradually smaller and smaller. And they also come from the bank lending survey, where the standards of tightness are decreasing, even though they remain tight from a historical perspective. And the interesting thing is that, for the first time, we’re observing a pickup in demand for loans.

Also, when again we examine the reasons for the tight supply, we see – and I think this has been going on now for three or four months – we see that risk perception, or risk aversion, has lost importance as a factor, reducing supply or increasing tightness.

On the second question, we’ll certainly keep in mind your suggestion. And our staff is continuously improving, and we are really worried and we want to take action on this. And we’re very well aware. But one has to understand one thing, that the ECB was not alone in overestimating inflation. And to some extent, as I’ve said many times, much of the fact that inflation has been lower than estimated and expected was due, first, to energy prices and food prices, until the third quarter of 2012 and, second, to the exchange rate developments thereafter.

Question: Mr Draghi, please allow me to ask you two questions on a more general level. During the euro crisis, the ECB has increased its non-standard measures. It has acquired a lot of new functions and increased its influence, if not to say, perhaps, its power. How would you describe the change of character of the ECB? In other words, where is the ECB standing now, compared to its origins? And secondly, regarding your remarks in London a few days ago concerning your suggestions that politicians should move toward more fiscal integration, how important is this, not only in order to solve the crisis, but also to make the ECB a more traditional and more normal central bank again?

Draghi: When the crisis erupted, the ECB was still a young institution. I would say that the ECB has grown a lot during the crisis. The crisis was, and still is, an extraordinary time that required from the ECB the use of extraordinary instruments. That was, I would say, our first responsibility.

But this responsibility was actually implemented always in a way to retain our mandate. So, we use extraordinary instruments to respond to extraordinary needs, always within our mandate. And our mandate was to maintain price stability.

In this sense, the ECB hasn’t really changed with respect to its fundamental characters. It has grown in having more instruments, in becoming more adequate to respond to the varying needs of a difficult economic situation. But it hasn’t changed in its fundamental pillars, which are the ones that justify its existence.

The second point, I’m not sure I actually spoke of greater fiscal integration. The point that I’ve made, by now, several times, is the following. This monetary union is an unfinished union. We’ve made enormous progress on the monetary side, with the creation of the ECB and the euro. We’ve made significant progress in sharing budgetary sovereignty, in sharing common rules, in accepting having common rules in the budgetary area. We’ve made great progress in creating a banking union.

Now, we’ll probably make further progress in creating what the new President of the Commission, Jean-Claude Juncker, called a ‘capital markets union’. And I see this as a likely possibility in the future.

But there is one further area which has acquired, if anything, even greater importance during the crisis, which is the area of structural reforms. And that’s where I said several times that it’s probably high time now to start sharing sovereignty in that area as well, taking the structural reforms area in the marketplace, product reforms, Single Market legislation, implementation and labour market reforms, under common union discipline – in other words, trying to replicate our success in the budgetary area also in the structural reforms.

Question: We had some really bad news on Italian GDP yesterday, which has led to questions whether Renzi is going to be able to fulfil his reform agenda. And more broadly than that, we’re seeing very weak growth, even in countries that have implemented structural reform. We’re not seeing growth really at a rate that’s going to cut into very, very high unemployment. As you’ve just said, you’ve mentioned a lot of times that we should see more integration, more centralisation on structural reform. But given that we haven’t got that yet, how politically feasible is it that we’re going to see these structural reforms when the short-term gains just are going to be pretty non-existent and unemployment is going to remain, it seems, very high if growth remains this weak.

And for my second question, a lot of economists view QE by the Bank of England and by the Fed as a form of insurance policy against a big macroeconomic shock. You’ve noted in your comments so far today that we’ve seen a rise in the threat of such a shock. With inflation at 0.4%, aren’t we in a position where the ECB is adopting a very risky strategy, where there is very little buffer against an outright episode of deflation, if there is a big macroeconomic shock?

Draghi: On your first question, one of the components of the low GDP figure for Italy is the significantly low level of private investment, while one would observe a rebound in private consumption. As far as private investment is concerned, one observes a very low figure, especially low figure of private investment. This isn’t unique in the euro area. The levels of private investment for the euro area as a whole is low, and certainly much lower than it is in other parts of the world, like in the United States.

Then we ask ourselves why this is so. Now, certainly it’s not the cost of capital, because interest rates, nominal and real interest rates, have been low. And in some parts of the euro area they are negative, and have been negative for quite a long time.

So the answers are: one has to do with expected demand. But the second answer has to do with the reforms, uncertainty, the general uncertainty the lack of structural reforms produces a very powerful factor that discourages investment.

There are stories of investors who would like to create, to build plants and equipment and create jobs, but it takes them months to get an authorisation to do so. There are stories of young people who tried to open their business, and it takes 8 to9 months before they can do so. That has nothing to do with monetary policy.

So it’s mostly the lack of structural reforms. I keep on saying the same thing, really – reforms in the labour market, in the product markets, in the competition, in the judiciary and so on and so forth. These would be the reforms which actually have and have shown to have a short-term benefit.

You don’t have to wait long time, because you know one of the common counterarguments to this is structural reforms take time to actually do them and also take time to produce a result. Well, as some of our countries show, this isn’t true. In these countries, unemployment is going down and output is going up. So some of these reforms have an immediate benefit. Others clearly do need much longer time.

I’m sorry. Your other question was?

Question: The idea that a lot of economists think that QE was undertaken as an insurance policy against a big shock, and now there’s very little wiggle room if there is such a shock for the ECB with inflation at 0.4 %.

Draghi: Well, let me say that the monetary policy announcements of last June have been successful. They have been successful, not only the various monetary policy announcements, but especially so the negative deposit rate, the negative rate on our deposit facility was considered to be one of the reasons for this success.

We basically decoupled our monetary conditions from those of the United States, and if you compare conditions with the beginning of May, when I first announced likely action on this front, you see that forward rate, the 1-year in 4 years OIS forward rate declined by 45basis points, the three months Euribor by 13 basis points. Excess liquidity is now at 140 billion, and it’s been stable over 100 billion. There has been a general compression in liquidity premia.

But also, there is another consideration to make, and that is that the fundamentals for a weaker exchange rate are today much better than they were two or three months ago. And this depends on factors that were, in a sense, in the baseline, like a slowing net trade surplus, but also depends on factors like there has been a decline in short-term capital inflows.

There has been a quite significant increase in the short- term positions on the euro, as recorded by the CFTC [Commodity Futures Trading Commision]. In other words, markets had perceived that the euro, that monetary policies in the euro area and in the United States are, and are going to stay, on a diverging path for a long period of time.

Other central banks have been reducing their exposure to the euro. And if you look at how markets are expecting real rates to be for the foreseeable future, meaning until 2019, current expectations are that real rates will remain negative in the euro area for a much longer time than they will be in the United States. I think that is one of the major developments that I would pick up from what happened in the last three, four months.

Question: My question is about the ABS purchases on — a bit on the terminology side. You said you have intensified the preparatory work with the expectation to go ahead with it. Assuming it does go ahead, would you have any objections towards calling it a QE? Would you call it QE, ECB version? Or is it going to be something fundamentally different from other central banks?

Draghi: Well, no. It depends very much on what we define by QE. If we define QE as broad-based asset purchases, then QE would include ABS, but would certainly not be reduced to ABS only. The QE broad asset purchases programmes include government bonds, in general public assets, and private assets. So ABS would be an example of private assets, but then you have QE into government bonds that are still on the table.

Question: How was it possible that with the Troika in Portugal for the past three years, no one noticed that Espirito Santo was a problem? And doesn’t this affect the other investors for the future situations? And does it not create doubts about the efficiency of the monitoring?

Draghi: Well, I can’t comment directly on any individual banks, but what I can say about what the Portuguese authorities have done in this case, they certainly took swift action on that case. Both they and the European [Commission’s] competition arm worked very well together and basically addressed a situation which could be potentially complex.

The market reaction both in Portugal and out of Portugal basically confirmed this view, this view that authorities have been swift and effective, and what could have been a systemic incident is actually now considered an incident, an episode which is restricted to this bank and to the owners of this bank. I’m using incident as a euphemism, but you understand what I mean.

So it’s just generally perceived as an episode that is being kept contained as far as this bank is concerned and has not affected neither the banking sector in Portugal nor Portugal at large nor other markets outside Portugal.

Question: A quick follow-up on the previous question, on the Banco Espirito Santos. It had an impact on the accounts, for instance, of Credit Agricole in France. I was wondering if in the comprehensive assessment that you’re conducting of banks, this question of cross-holding in banks is being taken into account, not only in terms of shareholdings, but also in terms of bond holdings of banks for bonds of other banks?

And my other question goes back to the not only the recession in Italy, but also the slowing of other countries, such as Germany and France, so would you characterise from what you said previously these countries have not done enough reforms? And would public investment take the place of the lacking private investment to compensate for this insufficient growth?

Draghi: I would ask the Vice President to respond to the first question.

Constâncio: Well, the asset quality review includes all portfolios, and that includes also, of course, the exposures and securities that one bank may have on other banks and those assets are then subject to the exam to see if they are properly valued in the balance sheet of the banks. So the aspect that you mentioned, it’s certainly included in the AQR.

Draghi: Now, we have to distinguish between countries that have done reforms and countries that have done nothing or have done very little reforms. You mentioned Germany. In the case of Germany, the slowdown, we have, first of all, to assess the full impact of these what I call technical factors. And we will be able to do so in the coming days, namely less working days for this.

But it’s quite clear that if the geopolitical risks materialize, it’s quite clear that the next two quarters will show lower growth. A completely different story is for countries that haven’t done reforms or have done very little of them, where you’ve been observing this weakness now for quarter after quarter. And that’s where — you mentioned public investment, that’s what I meant by growth-friendly fiscal consolidation. These countries have to do a growth-friendly fiscal consolidation, meaning fewer taxes. We are talking about a part of the world where taxation is the highest.

And these countries have the highest taxation in the highest taxation part of the of the world. So lower taxes, lower current expenditure, and possibly higher government investment, government investment expenditure, public investment expenditure.

But all this is possible only if the better conditions are complemented by structural reforms. I think I made this example last time when I said TLTROs offers very good financing conditions to banks, but again, if one can’t open a new business shop, there’s no point in given in more credit. You won’t know what to do with this.

Same thing with taxation. You lower taxes. Certainly people would welcome this very much, but if they cannot actually translate these lower taxes into better business, it’s pointless to do so.

Question: Maybe following up your statement before on inflation again, does the ECB expect that in the short to medium term there will be inflation rates going more apart within European countries? Take Germany. Inflation should rise maybe above the target of 2 %, and this is supported by higher wages you heard the debate in the last days, while other countries in the south or periphery in times of very low inflation, so good deflation, maybe, are tied with ongoing reforms. So this divergence is complicated maybe for you to interpret, but, is this an expectation of the ECB, as well?

And, secondly, maybe on France — I guess you have it in mind when you tell some countries you should have higher momentum of reforms. France is again and again claiming that ECB should do more for the recovery and to combat inflation, low inflation. But could you say to Paris maybe one more time that they should focus on these reforms and not fear maybe that these reforms could be tied with low inflation or maybe deflation, like in the south of the eurozone?

And finally, maybe a very personal question, but do you intend to spend some holiday in Italy to sustain the recovery of your home country?

Draghi: On the first part, I think your question reveals the complexity of the issue. We have countries where inflation will have to go above 2 %. And certainly the aim of the ECB, the objective of the ECB and the way price stability has been interpreted by the Governing Council of the ECB all throughout its existence, almost all throughout its existence, is that inflation should go at below but close to 2 %, and we are far from that objective.

So any development that would bring this inflation rate towards the 2 % is welcome. But it’s not the ECB business to determine wages for the world, for the euro area, or for single countries. The wage determination is in the hands of social partners.

For the other countries, the countries that now are having deflation, the key question — there’s no doubt that this sort of negative growth in prices depends on the lack of demand, but also on relative price adjustment. And then the key question is, is this going to be a short-term affair? In which case, it would not be a source of deflation.

Or is it going to last a long time? And it can last a long time for at least two reasons. One is that there are self-fulfilling expectations of continuously falling prices, which lead people to postpone their expenditure plans and, therefore, cause further fall in prices.

We are not seeing this sort of phenomenon at the present time. But there is another reason. What we define by a relative price adjustment often is not a relative price adjustment within certain sectors, where simply people just change prices in their catalogues. Often, it reflects a different reality where entire sectors are going to be annihilated, are going to be destroyed, and new productions have to take place, new sectors have to start their activity.

And this is a much longer process that doesn’t have to do necessarily much with expectations and self-fulfilling expectations, but it takes — it may take a long time, because it takes changes — it takes movements of factors, people from one sector to another, and we may well observe this phenomenon in the so-called deflation countries.

On the other point you made about what the ECB is doing, well, I listed before why the fundamentals for a weaker exchange rate are now better than they were a few months ago. I think this is quite relevant. And I listed a series of factors that I think I should not repeat now.

But the main factor is that basically monetary policies in Europe and in the United States and in UK are going to stay divergent, are on diverging path for a long time, and a much longer time in Europe than elsewhere so I think that’s the point.

But, again, let’s not forget: the creation of better financial or tax conditions are a necessary, but not a sufficient condition for restoring growth.

Yes, I will go to Italy. And I will not participate to the recovery of my country.

Question: I just want to follow up on the question on ABS purchases and the first answer you gave on this topic, because it seems to suggest that such purchases are already a done deal and that it’s not a question of if, but only a question of when and how. Is that correct? And the second question is on inflation expectations.

I guess next week we will get the new survey of professional forecasters. Did you already get the results of some first results today? And what — how do they look like, especially regarding longer-term inflation expectations?

Draghi: Well, the second question I can’t really say anything about. But as far as I know, they are confirming our medium- to long-term outlook. As I said before, short-term inflation expectations have been declining but not in the medium to long term.

On the other point about ABS, well, in a sense, you know, ABS is just a name. And we know that the traditional ABS that were being traded before the crisis had many — to be charitable — many imperfections. And we certainly would not and could not recreate that sort of market, because it was considered — some of these imperfections were actually considered one of the major roots or the major causes of the financial crisis. So our effort isn’t simple, because we want to recreate a market that is limited to a product that is — as I said before — simple, transparent and real.

Second, this market can actually — we do — I mean, Bank of England and ourselves believe that this market can restart, but the economics of this market must work. And what is now one of the major impediments to this is the present regulation. Having said that, no matter what regulators will be doing, we want to be ready. And that’s why we’ve intensified preparation.

Question: My first question, I’d like to go back to Banco Espirito Santos. And you said that the problem was contained for now, but how confident are you that this will not spread actually to the rest of the region and reignite the crisis? And to what extent are the problems at BES actually symptomatic of unresolved problems in the Eurozone periphery?

My second question, I’d like to ask you a little bit more about the Russian sanctions and, in particular, those affecting the five major Russian state-owned banks. How are you going to make sure that the funds that these banks, eurozone subsidiaries are taking from the ECB are not going to leave the eurozone?

Draghi: You know, on the first question, I think I’ve answered. The action undertaken by the authorities, Portuguese authorities, by the ECB and by the [European Commission’s] Directorate General for Competition was, I think, swift and effective, the creation of the bad bank and a good bank, and basically proved to be quite effective in reassuring markets and reassuring also other players of the same sector, namely other banks in Portugal and more generally banks everywhere.

Now, of course, these are the initial decisions.There’s still a lot of work to do about that, in terms especially of transferring the assets between the two entities and the prices at which they’ll be transferred, the treatment of the exposure in Angola.

Basically, the entity that was created is an entity that has acknowledged the losses, the impairments, and has been now in the hands of the resolution fund. Oh, on this point, let me just make a point, which was a source of some confusion. The resolution fund owns this bank and probably, and hopefully soon, will sell it back. In this sense, there was no public money directly or eventually involved into this.

The differences in prices that could arise from the transfers would have to be filled by the banking sector, not by the government. I mean, this is something that ought to be clarified, so that’s one point. So, so far, we frankly didn’t have any sign that this is so.

One more word about this. We’ve seen — this is ta major episode, but we’ve seen other minor episodes of dramatic changes in the corporate structure of banks since our AQR effort was launched. We’ve seen many banks raising significant amounts of capital in the last year. And I think that is an important — very important element that should not be underestimated because it’s so crucial to repairing the bank lending channel in the euro area.

Now, on Russia, you were asking about the Russian subsidiaries in the euro area. These banks will be basically moving within the EU regulations, but we will do something slightly more than that, in the sense that these banks will have access to refinancing, but they will be asked to announce their requirements first. And, second, approval will be granted if it has been confirmed that the requested liquidity will not be used to circumvent EU restrictive measures. And so banks will have to explain why they need the money, and the national central bank’s inspectors, supervisors, will assess their statements.

Comentarii

Adauga un comentariu

Alte stiri din categoria: Noutati BCE

Acord intre BCE si BNR pentru supravegherea bancilor

• BCE semnează Memorandumul de înțelegere cu autoritățile naționale competente din șase state membre ale UE care nu participă la supravegherea bancară europeană. • Țările care fac obiectul Memorandumului sunt Cehia, Danemarca, Polonia, România, Suedia și Ungaria.• Memorandumul consolidează cooperarea în materie de supraveghere prin partajarea de informații și promovează o cultură comună în domeniul supravegherii.Banca Centrală Europeană (BCE) a încheiat un Memorandum de înțelegere multilateral cu autoritățile naționale competente (ANC) ale celor șase state membre ale UE care nu participă la supravegherea bancară europeană, conform unui comunicat de presa, in care se adauga:Memorandumul va asigura un cadru prin intermediul căruia Cehia, Danemarca, Polonia, România, Suedia și Ungaria vor face schimb de informații și își vor coordona activitățile de supraveghere.Acordul urmărește să intensifice în continuare cooperarea în materie de supraveghere la nivel european, pe fundamentul... detalii

Banca Centrala Europeana (BCE) explica de ce a majorat dobanda la 2%

Banca Centrala Europeana (BCE) explica de ce a majorat dobanda la 2%, in cadrul unei conferinte de presa sustinute de Christine Lagarde, președinta BCE, si Luis de Guindos, vicepreședintele BCE.Iata... detalii

BCE creste dobanda la 2%, dupa ce inflatia a ajuns la 10%

Banca Centrala Europeana (BCE) a majorat dobanda de referinta pentru tarile din zona euro cu 0,75 puncte, la 2% pe an, din cauza cresterii substantiale a inflatiei, ajunsa la aproape 10% in septembrie, cu mult peste tinta BCE, de doar 2%.In aceste conditii, BCE a anuntat ca va continua sa majoreze dobanda de politica monetara.De asemenea, BCE a luat masuri pentru a reduce nivelul imprumuturilor acordate bancilor in perioada pandemiei coronavirusului, prin majorarea dobanzii aferente acestor facilitati, denumite operațiuni țintite de refinanțare pe termen mai lung (OTRTL).Comunicatul BCEConsiliul guvernatorilor a decis astăzi să majoreze cu 75 puncte de bază cele trei rate ale dobânzilor reprezentative ale BCE. Prin această majorare substanțială a ratelor dobânzilor pentru a treia oară consecutiv, Consiliul guvernatorilor a înregistrat progrese considerabile în procesul de retragere a măsurilor acomodative de politică monetară. Consiliul... detalii

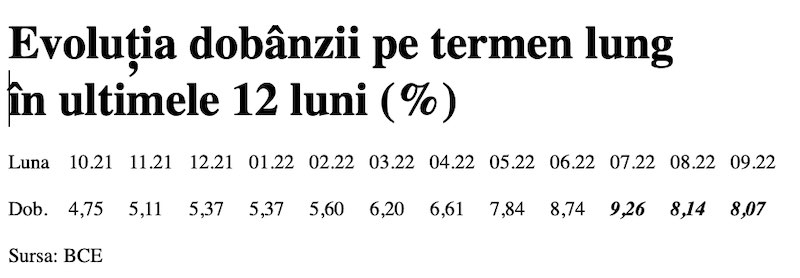

Dobânda pe termen lung a continuat să scadă in septembrie 2022. Ecartul față de Polonia și Cehia, redus semnificativ

Dobânda pe termen lung pentru România a scăzut în septembrie 2022 la valoarea medie de 8,07%, potrivit datelor publicate de Banca Centrală Europeană. Acest indicator, cu referința la un termen... detalii

Rata dobanzii pe termen lung pentru Romania, in crestere la 2,96%

Rata dobanzii pe termen lung pentru Romania, in crestere la 2,96%

BCE recomanda bancilor sa nu plateasca dividende

BCE recomanda bancilor sa nu plateasca dividende

Modul de functionare a relaxarii cantitative (quantitative easing – QE)

Modul de functionare a relaxarii cantitative (quantitative easing – QE)

Dobanda la euro nu va creste pana in iunie 2020

Dobanda la euro nu va creste pana in iunie 2020

BCE trebuie sa fie consultata inainte de adoptarea de legi care afecteaza bancile nationale

BCE trebuie sa fie consultata inainte de adoptarea de legi care afecteaza bancile nationale

BCE a publicat avizul privind taxa bancara

BCE a publicat avizul privind taxa bancara

BCE va mentine la 0% dobanda de referinta pentru euro cel putin pana la finalul lui 2019

BCE va mentine la 0% dobanda de referinta pentru euro cel putin pana la finalul lui 2019

ECB: Insights into the digital transformation of the retail payments ecosystem

ECB: Insights into the digital transformation of the retail payments ecosystem

ECB introductory statement on Governing Council decisions

ECB introductory statement on Governing Council decisions

Speech by Mario Draghi, President of the ECB: Sustaining openness in a dynamic global economy

Vezi toate stirile

Speech by Mario Draghi, President of the ECB: Sustaining openness in a dynamic global economy

Vezi toate stirile

Criza COVID-19

- In majoritatea unitatilor BRD se poate intra fara certificat verde

- La BCR se poate intra fara certificat verde

- Firmele, obligate sa dea zile libere parintilor care stau cu copiii in timpul pandemiei de coronavirus

- CEC Bank: accesul in banca se face fara certificat verde

- Cum se amana ratele la creditele Garanti BBVA

Topuri Banci

- Topul bancilor dupa active si cota de piata in perioada 2022-2015

- Topul bancilor cu cele mai mici dobanzi la creditele de nevoi personale

- Topul bancilor la active in 2019

- Topul celor mai mari banci din Romania dupa valoarea activelor in 2018

- Topul bancilor dupa active in 2017

Asociatia Romana a Bancilor (ARB)

- Băncile din România nu au majorat comisioanele aferente operațiunilor în numerar

- Concurs de educatie financiara pentru elevi, cu premii in bani

- Creditele acordate de banci au crescut cu 14% in 2022

- Romanii stiu educatie financiara de nota 7

- Gradul de incluziune financiara in Romania a ajuns la aproape 70%

ROBOR

- ROBOR: ce este, cum se calculeaza, ce il influenteaza, explicat de Asociatia Pietelor Financiare

- ROBOR a scazut la 1,59%, dupa ce BNR a redus dobanda la 1,25%

- Dobanzile variabile la creditele noi in lei nu scad, pentru ca IRCC ramane aproape neschimbat, la 2,4%, desi ROBOR s-a micsorat cu un punct, la 2,2%

- IRCC, indicele de dobanda pentru creditele in lei ale persoanelor fizice, a scazut la 1,75%, dar nu va avea efecte imediate pe piata creditarii

- Istoricul ROBOR la 3 luni, in perioada 01.08.1995 - 31.12.2019

Taxa bancara

- Normele metodologice pentru aplicarea taxei bancare, publicate de Ministerul Finantelor

- Noul ROBOR se va aplica automat la creditele noi si prin refinantare la cele in derulare

- Taxa bancara ar putea fi redusa de la 1,2% la 0,4% la bancile mari si 0,2% la cele mici, insa bancherii avertizeaza ca indiferent de nivelul acesteia, intermedierea financiara va scadea iar dobanzile vor creste

- Raiffeisen anunta ca activitatea bancii a incetinit substantial din cauza taxei bancare; strategia va fi reevaluata, nu vor mai fi acordate credite cu dobanzi mici

- Tariceanu anunta un acord de principiu privind taxa bancara: ROBOR-ul ar putea fi inlocuit cu marja de dobanda a bancilor

Statistici BNR

- Deficitul contului curent, aproape 20 miliarde euro după primele nouă luni

- Deficitul contului curent, aproape 18 miliarde euro după primele opt luni

- Deficitul contului curent, peste 9 miliarde euro pe primele cinci luni

- Deficitul contului curent, 6,6 miliarde euro după prima treime a anului

- Deficitul contului curent pe T1, aproape 4 miliarde euro

Legislatie

- Legea nr. 311/2015 privind schemele de garantare a depozitelor şi Fondul de garantare a depozitelor bancare

- Rambursarea anticipata a unui credit, conform OUG 50/2010

- OUG nr.21 din 1992 privind protectia consumatorului, actualizata

- Legea nr. 190 din 1999 privind creditul ipotecar pentru investiții imobiliare

- Reguli privind stabilirea ratelor de referinţă ROBID şi ROBOR

Lege plafonare dobanzi credite

- Care este dobanda maxima la un credit IFN?

- BNR propune Parlamentului plafonarea dobanzilor la creditele bancilor intre 1,5 si 4 ori peste DAE medie, in functie de tipul creditului; in cazul IFN-urilor, plafonarea dobanzilor nu se justifica

- Legile privind plafonarea dobanzilor la credite si a datoriilor preluate de firmele de recuperare se discuta in Parlament (actualizat)

- Legea privind plafonarea dobanzilor la credite nu a fost inclusa pe ordinea de zi a comisiilor din Camera Deputatilor

- Senatorul Zamfir, despre plafonarea dobanzilor la credite: numai bou-i consecvent!

Anunturi banci

- Cate reclamatii primeste Intesa Sanpaolo Bank si cum le gestioneaza

- Platile instant, posibile la 13 banci

- Aplicatia CEC app va functiona doar pe telefoane cu Android minim 8 sau iOS minim 12

- Bancile comunica automat cu ANAF situatia popririlor

- BRD bate recordul la credite de consum, in ciuda dobanzilor mari, si obtine un profit ridicat

Analize economice

- Inflația anuală, peste pragul de 5% în 2024

- Deficit bugetar de -7,12% din PIB, după 11 luni din 2024

- România, „lanterna roșie†a cheltuielilor pentru cercetare-dezvoltare în UE

- Deficitul contului curent, peste 24 miliarde euro după primele zece luni

- Deficit comercial record în octombrie 2024

Ministerul Finantelor

- Datoria publică, 51,4% din PIB la mijlocul anului

- Deficit bugetar de 3,6% din PIB după prima jumătate a anului

- Deficit bugetar de 3,4% din PIB după primele cinci luni ale anului

- Deficit bugetar îngrijorător după prima treime a anului

- Deficitul bugetar, -2,06% din PIB pe primul trimestru al anului

Biroul de Credit

- FUNDAMENTAREA LEGALITATII PRELUCRARII DATELOR PERSONALE IN SISTEMUL BIROULUI DE CREDIT

- BCR: prelucrarea datelor personale la Biroul de Credit

- Care banci si IFN-uri raporteaza clientii la Biroul de Credit

- Ce trebuie sa stim despre Biroul de Credit

- Care este procedura BCR de raportare a clientilor la Biroul de Credit

Procese

- ANPC pierde un proces cu Intesa si ARB privind modul de calcul al ratelor la credite

- Un client Credius obtine in justitie anularea creditului, din cauza dobanzii prea mari

- Hotararea judecatoriei prin care Aedificium, fosta Raiffeisen Banca pentru Locuinte, si statul sunt obligati sa achite unui client prima de stat

- Decizia Curtii de Apel Bucuresti in procesul dintre Raiffeisen Banca pentru Locuinte si Curtea de Conturi

- Vodafone, obligata de judecatori sa despagubeasca un abonat caruia a refuzat sa-i repare un telefon stricat sau sa-i dea banii inapoi (decizia instantei)

Stiri economice

- Deficitul comercial a depașit pragul de 30 miliarde euro în noiembrie 2024

- Inflația anuală a crescut la 5,11%, prin efect de bază

- Datoria publică, 54,4% din PIB la finele lunii septembrie 2024

- România, tot prima dar în trendul UE la inflația anuală

- Datoria publică, 52,7% din PIB la finele lunii august 2024

Statistici

- România, pe locul trei în UE la creșterea costului muncii în T2 2024

- Cheltuielile cu pensiile - România, pe locul 19 în UE ca pondere în PIB

- Dobanda din Cehia a crescut cu 7 puncte intr-un singur an

- Care este valoarea salariului minim brut si net pe economie in 2024?

- Cat va fi salariul brut si net in Romania in 2024, 2025, 2026 si 2027, conform prognozei oficiale

FNGCIMM

- Programul IMM Invest continua si in 2021

- Garantiile de stat pentru credite acordate de FNGCIMM au crescut cu 185% in 2020

- Programul IMM invest se prelungeste pana in 30 iunie 2021

- Firmele pot obtine credite bancare garantate si subventionate de stat, pe baza facturilor (factoring), prin programul IMM Factor

- Programul IMM Leasing va fi operational in perioada urmatoare, anunta FNGCIMM

Calculator de credite

- ROBOR la 3 luni a scazut cu aproape un punct, dupa masurile luate de BNR; cu cat se reduce rata la credite?

- In ce mall din sectorul 4 pot face o simulare pentru o refinantare?

Noutati BCE

- Acord intre BCE si BNR pentru supravegherea bancilor

- Banca Centrala Europeana (BCE) explica de ce a majorat dobanda la 2%

- BCE creste dobanda la 2%, dupa ce inflatia a ajuns la 10%

- Dobânda pe termen lung a continuat să scadă in septembrie 2022. Ecartul față de Polonia și Cehia, redus semnificativ

- Rata dobanzii pe termen lung pentru Romania, in crestere la 2,96%

Noutati EBA

- Bancile romanesti detin cele mai multe titluri de stat din Europa

- Guidelines on legislative and non-legislative moratoria on loan repayments applied in the light of the COVID-19 crisis

- The EBA reactivates its Guidelines on legislative and non-legislative moratoria

- EBA publishes 2018 EU-wide stress test results

- EBA launches 2018 EU-wide transparency exercise

Noutati FGDB

- Banii din banci sunt garantati, anunta FGDB

- Depozitele bancare garantate de FGDB au crescut cu 13 miliarde lei

- Depozitele bancare garantate de FGDB reprezinta doua treimi din totalul depozitelor din bancile romanesti

- Peste 80% din depozitele bancare sunt garantate

- Depozitele bancare nu intra in campania electorala

CSALB

- Sistemul bancar romanesc este deosebit de bine pregatit pentru orice fel de socuri

- La CSALB poti castiga un litigiu cu banca pe care l-ai pierde in instanta

- Negocierile dintre banci si clienti la CSALB, in crestere cu 30%

- Sondaj: dobanda fixa la credite, considerata mai buna decat cea variabila, desi este mai mare

- CSALB: Romanii cu credite caută soluții pentru reducerea ratelor. Cum raspund bancile

First Bank

- Ce trebuie sa faca cei care au asigurare la credit emisa de Euroins

- First Bank este reprezentanta Eurobank in Romania: ce se intampla cu creditele Bancpost?

- Clientii First Bank pot face plati prin Google Pay

- First Bank anunta rezultatele financiare din prima jumatate a anului 2021

- First Bank are o noua aplicatie de mobile banking

Noutati FMI

- FMI: criza COVID-19 se transforma in criza economica si financiara in 2020, suntem pregatiti cu 1 trilion (o mie de miliarde) de dolari, pentru a ajuta tarile in dificultate; prioritatea sunt ajutoarele financiare pentru familiile si firmele vulnerabile

- FMI cere BNR sa intareasca politica monetara iar Guvernului sa modifice legea pensiilor

- FMI: majorarea salariilor din sectorul public si legea pensiilor ar trebui reevaluate

- IMF statement of the 2018 Article IV Mission to Romania

- Jaewoo Lee, new IMF mission chief for Romania and Bulgaria

Noutati BERD

- Creditele neperformante (npl) - statistici BERD

- BERD este ingrijorata de investigatia autoritatilor din Republica Moldova la Victoria Bank, subsidiara Bancii Transilvania

- BERD dezvaluie cat a platit pe actiunile Piraeus Bank

- ING Bank si BERD finanteaza parcul logistic CTPark Bucharest

- EBRD hails Moldova banking breakthrough

Noutati Federal Reserve

- Federal Reserve anunta noi masuri extinse pentru combaterea crizei COVID-19, care produce pagube "imense" in Statele Unite si in lume

- Federal Reserve urca dobanda la 2,25%

- Federal Reserve decided to maintain the target range for the federal funds rate at 1-1/2 to 1-3/4 percent

- Federal Reserve majoreaza dobanda de referinta pentru dolar la 1,5% - 1,75%

- Federal Reserve issues FOMC statement

Noutati BEI

- BEI a redus cu 31% sprijinul acordat Romaniei in 2018

- Romania implements SME Initiative: EUR 580 m for Romanian businesses

- European Investment Bank (EIB) is lending EUR 20 million to Agricover Credit IFN

Mobile banking

- Comisioanele BRD pentru MyBRD Mobile, MyBRD Net, My BRD SMS

- Termeni si conditii contractuale ale serviciului You BRD

- Recomandari de securitate ale BRD pentru utilizatorii de internet/mobile banking

- CEC Bank - Ghid utilizare token sub forma de card bancar

- Cinci banci permit platile cu telefonul mobil prin Google Pay

Noutati Comisia Europeana

- Avertismentul Comitetului European pentru risc sistemic (CERS) privind vulnerabilitățile din sistemul financiar al Uniunii

- Cele mai mici preturi din Europa sunt in Romania

- State aid: Commission refers Romania to Court for failure to recover illegal aid worth up to €92 million

- Comisia Europeana publica raportul privind progresele inregistrate de Romania in cadrul mecanismului de cooperare si de verificare (MCV)

- Infringements: Commission refers Greece, Ireland and Romania to the Court of Justice for not implementing anti-money laundering rules

Noutati BVB

- BET AeRO, primul indice pentru piata AeRO, la BVB

- Laptaria cu Caimac s-a listat pe piata AeRO a BVB

- Banca Transilvania plateste un dividend brut pe actiune de 0,17 lei din profitul pe 2018

- Obligatiunile Bancii Transilvania se tranzactioneaza la Bursa de Valori Bucuresti

- Obligatiunile Good Pople SA (FRU21) au debutat pe piata AeRO

Institutul National de Statistica

- Deficitul contului curent, peste 26 miliarde euro în noiembrie 2024

- Comerțul cu amănuntul - în creștere cu 8% pe primele 10 luni

- Deficitul balanței comerciale la 9 luni, cu 15% mai mare față de aceeași perioadă a anului trecut

- Producția industrială, în scădere semnificativă

- Pensia reală, în creștere cu 8,7% pe luna august 2024

Informatii utile asigurari

- Data de la care FGA face plati pentru asigurarile RCA Euroins: 17 mai 2023

- Asigurarea împotriva dezastrelor, valabilă și in caz de faliment

- Asiguratii nu au nevoie de documente de confirmare a cutremurului

- Cum functioneaza o asigurare de viata Metropolitan pentru un credit la Banca Transilvania?

- Care sunt documente necesare pentru dosarul de dauna la Cardif?

ING Bank

- La ING se vor putea face plati instant din decembrie 2022

- Cum evitam tentativele de frauda online?

- Clientii ING Bank trebuie sa-si actualizeze aplicatia Home Bank pana in 20 martie

- Obligatiunile Rockcastle, cel mai mare proprietar de centre comerciale din Europa Centrala si de Est, intermediata de ING Bank

- ING Bank transforma departamentul de responsabilitate sociala intr-unul de sustenabilitate