Vítor Constâncio, ECB: Understanding the yield curve

Understanding the yield curve

Opening address by Vítor Constâncio, Vice-President of the ECB,

at the ECB workshop “Understanding the yield curve: what has changed with the crisis?”,

Frankfurt, 8 September 2014

Ladies and gentlemen,

It is a great pleasure for me to welcome you on behalf of the Executive Board of the European Central Bank to this topical workshop on “Understanding the yield curve: what has changed with the crisis?”. This event is part of a sequence of very productive workshops on asset pricing that have been jointly organised by the ECB and the Bank of England for several years now. I am very pleased to see this established practice of collaboration across our two central banks continuing and gaining further ground.

I would also like to welcome all participants: colleagues from other central banks, among them many from the Federal Reserve System and from the co-organising Bank of England, the participants from academia, guests from the private sector and colleagues from the European Central Bank.

In my remarks today, I will first give a short overview of the role of the yield curve in monetary policy deliberations, mentioning also the impact of the crisis. I will then go on to talk about some topical and much discussed issues that are related to the challenges central banks face in interpreting the information coming from fixed income markets.

The role of the yield curve in monetary policy deliberations

As we all know, the understanding of the dynamic evolution and the forecasting of the yield curve has many practical applications: pricing asset and derivatives, devising strategies for public debt programs, managing risk and conducting monetary policy. An old simple use of the yield curve, more common in the US, was to use its slope to forecast recessions. In 2009, Rudebusch and Williams [1] published a paper about what they call “the puzzle of the enduring power of the yield curve” to forecast recessions. In 2006, when the US yield curve got inverted predicting a recession, the whole idea was dismissed as having finally failed only to be confirmed by the Great Recession. In a very recent paper, Chinn and Kucko [2] examine the issue for the US, the euro area and eight European countries. The results show that the slope indicator performance has deteriorated in recent years although it seems to work better than other leading indicators for some European countries.

Today we are mainly interested in examining the important role the yield curve has for the conduct of monetary policy.

The yield curve is important mainly for two reasons. First, it is an indicator of what the market is thinking about the expected path of future monetary policy. This follows because long-term rates under certain conditions reflect expectations of the future path of short-term rates. Of course, besides future rate expectations, longer maturity yields typically contain risk premia. The quantification of these premia is not without challenges even in normal times.

The second reason results from the yield curve being a key part of the transmission mechanism of monetary policy. Therefore, it is something the central bank wants to influence, not only just learn from. In particular, while the first step in the transmission process of monetary policy is typically related to very short-term interbank interest rates, the wider transmission requires that these effects spread more widely to medium- and longer-term rates. In the next step, the monetary policy impulse spreads to the pricing of assets that are relevant for the financing conditions of households and corporations, their consumption, production and investment decisions and, finally, inflation.

The impact of the crisis

Naturally, the crisis has brought up a number of challenges for our understanding of the yield curve.

For example, credit and liquidity premia have been important drivers of sovereign yields in the euro area and elsewhere, thereby complicating the process of inferring market expectations of the future path of policy, and also impairing the transmission mechanism of monetary policy to the wider economy. Moreover, high sovereign spreads in the euro area have raised the question of what is the appropriate yield curve to monitor. In an article in the July Monthly Bulletin we discussed this issue in the context of measuring the euro area risk-free rate. Should we use Bund yields, euro area average AAA rates or OIS rates, or does it depend on the matter at hand?

Incidentally, an intriguing question in a currency union is the following: if it is difficult to identify a risk-free rate in a currency union, this means that there is no risk-free asset either, besides the central bank’s own liabilities, the currency. Whether this peculiar situation adds to the challenges facing the central bank of a monetary union, in terms of signal-extraction and analysis of expectations, I leave to you as a topic for reflection.

The crisis has also proved the important role that central banks play in influencing the yield curve through both their conventional and unconventional policies; including forward guidance, asset purchases and enhanced credit support. This raises a host of questions about the relative effectiveness of these policies, but also about conventional yield curve models and whether they adequately capture the mechanisms that explain the role of these policies, particularly given that for tractability and simplicity real-world complications like credit and liquidity premia, pricing anomalies and even the influence of the macro economy and monetary policy are often not directly considered.

It is well known that during decades the fields of finance and macroeconomics dealt with interest rates, asset prices and the yield curve in a total different way and without much interaction. As Diebold and Rudebusch point out in their book published last year on “Yield curve modelling and forecasting” [3]: “ In macro models, the entire financial sector is often represented by a single interest rate with no accounting for credit or liquidity risk and no role for financial intermediation or financial frictions. Similarly, finance models often focus on the consistency of asset prices across markets with little regard for underlying macroeconomic fundamentals. To understand important aspects of the recent financial crisis … a joint macro-finance perspective is likely necessary”.

The macro-finance approach to the analysis of the yield curve had several developments even before the crisis. In 2006, Hördahl, Tristani and Vestin [4], (the last two, ECB researchers), published a paper embedding the analysis of the term structure of interest rates into a DSGE model. With a few changes in the standard framework of the time, they were able to replicate key features of the term structure usually present in the data. Diebold, Rudebusch and Aruoba, also in 2006 [5], provided a bidirectional connection between the factors of a dynamic Nelson-Siegel model of the yield and macro variables. The first factor, the level, showing a high correlation with inflation and the second factor, the slope, being highly correlated with real economy activity. Later, in 2007, Rudebusch and Wu [6] developed a macro-finance model with a no-arbitrage dynamic specification of the term structure and a small new Keynesian model. In an application of this model to the great moderation period, they find the level factor associated with the perceived inflation target of monetary policy and the slope factor connected with the cyclical response of monetary policy with the economy. The field of macro-finance continued to expand and recently focused on how to consider the zero lower bound into yield curve models and we have an example of that research in our workshop.

Current policy questions

Judged in terms of the number of policy questions, this is an excellent time to be doing research on yield curves. Yields in the euro area have recently fallen to record lows. Does this reflect the underlying fundamentals in the euro area, the expectation of additional monetary loosening, or some kind of mispricing by markets? What is the risk that yields could suddenly snap back to much higher levels?

For all the analysis that has been done on the effects of unconventional monetary policies on the yields curve, there is still a great deal of disagreement on the effectiveness of these policies and the main channels they work through. What can be said about this and how can we best evaluate the relative impact of these policies? As well as guiding the future use of these policies, this is also important for gauging the likely impact when these policies are removed. With the Fed about to end its asset purchases and both the Fed and Bank of England expected to start raising policy rates next year, long rates should have increased. However, in the US, after an increase last year following the May tapering announcement, long rates have been decreasing since the beginning of the year in what James Hamilton has called the bond market conundrum redux.

Given that the euro area is some way from exiting non-standard policies, a related issue is on the nature of the likely spillovers of the US monetary policy. At various times in the past, we have seen US and euro yields move very closely together but they have diverged somewhat recently. In contrast, UK and US rates are currently very closely linked. What determines the degree of coupling or decoupling between yields and what can we expect going forward? And finally, when do markets expect the ECB to start raising rates? Given the role of term premia and the impact of the zero lower bound, how can we best estimate this date?

The workshop papers and concluding remarks

Many of these issues are taken up in some way by the papers that are going to be discussed over the next day and a half. A couple of the papers will look at the impact of Treasury supply on yields, drawing on new research based on the US experience and also research on the economic mechanisms involved, the so-called portfolio balance channel. There are also some papers that look more specifically at recent asset purchase programmes and how they have affected yields and also the spillovers from them to other countries.

Other papers look at the impact of monetary policy on the yield curve, finding for example that monetary policy is one of the factors that explain movements in the term premium. There are also several papers that estimate so-called shadow rate models that recognise the zero lower bound that prevents interest rates going negative. There are also papers that look more specifically at euro area bonds markets during the crisis and the role of credit and liquidity premia and evidence of pricing anomalies, in both cases highlighting the role of the ECB’s interventions.

We are also pleased to welcome two keynote speakers from the US, Gregory Duffee and Glenn Rudebusch, who are both leading researchers in the literature, representing academia and the Federal Reserve System, respectively. Both will talk about the influence of unconventional monetary policy on the yield curve and it will be enlightening to hear their perspectives on the subject.

Finally, we have a distinguished panel of market experts, who have been primed to talk to some of the issues I have mentioned, followed by a Q & A, which should ensure that the workshop ends on a high note.

These are the reasons that make almost superfluous my wish for some stimulating discussions over the next day and a half and a very productive workshop.

Thank you for your attention.

[1]Rudebusch, G. and J. Williams, (2009), “Forecasting Recessions: The Puzzle of the Enduring Power of the Yield Curve,” Journal of Business & Economic Statistics, American Statistical Association, vol. 27(4).

[2]Chinn, M. and K. Kucko, (2014) “The predictive power of the yield curve across countries and time”, mimeo available at http://www.ssc.wisc.edu/~mchinn/Chinn_Kucko_Feb2014.pdf

[3] Diebold, F. X. and G. Rudebusch, (2013), “Yield curve modelling and forecasting: the dynamic Nelson-Siegel approach”, Princeton University Press.

[4]Hördahl P., O. Tristani and D. Vestin, (2006), “A joint econometric model of macroeconomic and term structure dynamics”, Journal of Econometrics, 131. See also by the same authors (2008), “The Yield Curve and Macroeconomic Dynamics,” Economic Journal, Royal Economic Society, vol. 118(533).

[5] Diebold, F. X., G. Rudebusch and S. B. Arouba, (2006), “The macroeconomy and the yield curve: a dynamic latent factor approach”, Journal of Econometrics, 131, 309-338

[6] Rudebusch, G. and T. Wu (2007) “Accounting for a shift in term structure behaviour with no-arbitrage and macro-finance models”, Journal of Money, Credit and Banking, 39, 395-422

Source: ECB

Comentarii

Nu există comentarii pentru această știre.

Adauga un comentariu

Alte stiri din categoria: Opinie

Suma minima de plata la card inseamna ca platesti o dobanda mare

"Consumatorii să fie atenți la câteva lucruri: Dacă rambursează doar suma minimă de plată la un card de credit, vor plăti dobândă, însă dacă vor plăti rata întreagă din luna... detalii

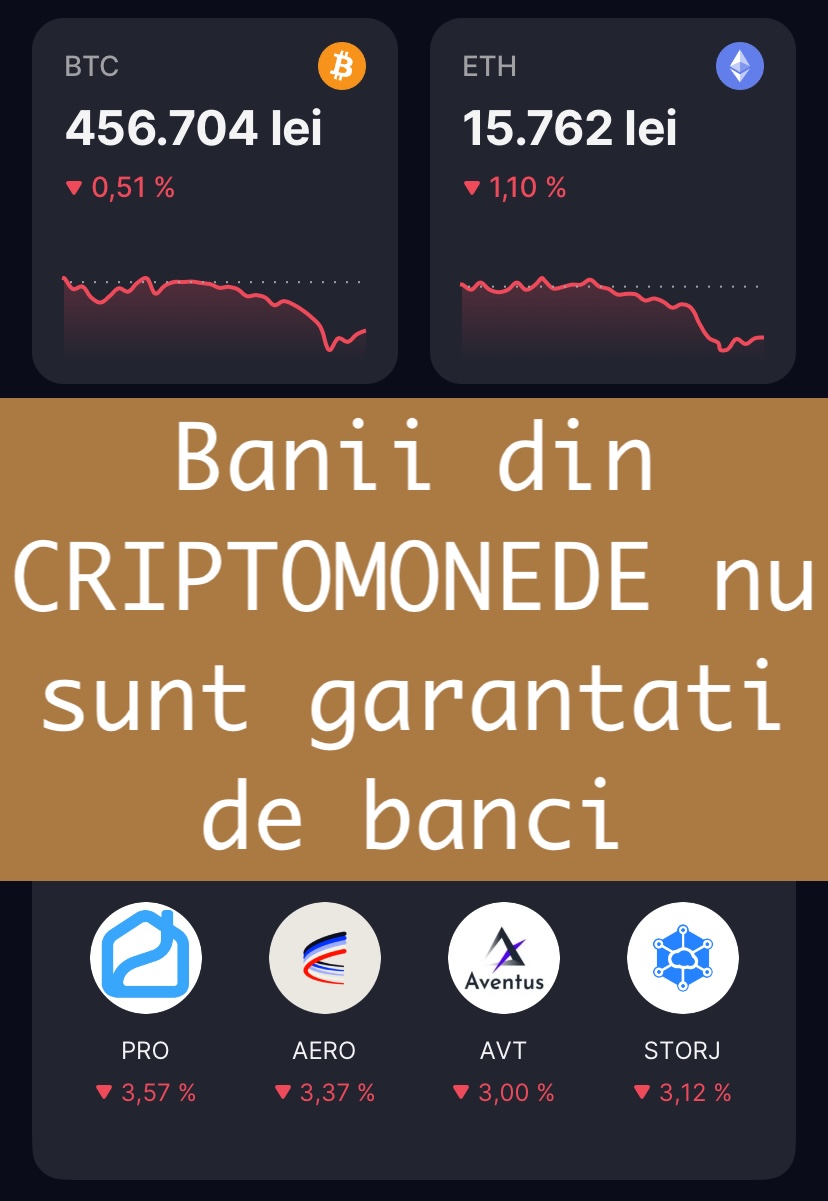

Nu cumparati criptomonede!

Presedintele american Trump si sotia lui si-au lansat o criptomoneda care a fost cumparata, fireste, de multi oameni, sporindu-i rapid valoarea. "O criptomeda a presedintelui SUA nu poate sa scada... detalii

Dobanda BNR ar putea scadea la 5,75% in 2025

Dobanda de politica monetara a BNR (Banca Nationala a Romaniei) ar putea fi scazuta de trei ori in acest an, la 5,75%, de la 6,5%, cat este in prezent, conform... detalii

Dobanda la euro ar putea scadea de la 3% la 1,5%, in 2025

Dobanda de politica monetara a Bancii Centrale Europene (BCE) ar putea scadea de la 3% in prezent la 1,5% pana la finalul lui 2025, prognozeaza economistii. „Ne asteptam ca BCE... detalii

Creditare iresponsabila promovata de un broker

Creditare iresponsabila promovata de un broker

Inflatia este si consecinta cresterii salariilor

Inflatia este si consecinta cresterii salariilor

ING ramane singura dintre bancile romanesti care-si face corect reclama la credite

ING ramane singura dintre bancile romanesti care-si face corect reclama la credite

Cardurile devin inutile: acum se pot face plati instant gratis din aplicatiile bancare

Cardurile devin inutile: acum se pot face plati instant gratis din aplicatiile bancare

Au neglijat bancile securitatea pentru digitalizare?

Au neglijat bancile securitatea pentru digitalizare?

BRD isi lichideaza filialele din Romania. Va fi vanduta si banca?

BRD isi lichideaza filialele din Romania. Va fi vanduta si banca?

De ce permit bancile transferuri catre platforme de criptomonede prin care se fac fraude online?

De ce permit bancile transferuri catre platforme de criptomonede prin care se fac fraude online?

Banca Transilvania implineste 30 de ani

Banca Transilvania implineste 30 de ani

De cand si cat de mult ar putea sa scada dobanzile in 2024?

De cand si cat de mult ar putea sa scada dobanzile in 2024?

Ce responsabilitate au bancile in cazul fraudelor online?

Vezi toate stirile

Ce responsabilitate au bancile in cazul fraudelor online?

Vezi toate stirile

Criza COVID-19

- In majoritatea unitatilor BRD se poate intra fara certificat verde

- La BCR se poate intra fara certificat verde

- Firmele, obligate sa dea zile libere parintilor care stau cu copiii in timpul pandemiei de coronavirus

- CEC Bank: accesul in banca se face fara certificat verde

- Cum se amana ratele la creditele Garanti BBVA

Topuri Banci

- Topul bancilor dupa active si cota de piata in perioada 2022-2015

- Topul bancilor cu cele mai mici dobanzi la creditele de nevoi personale

- Topul bancilor la active in 2019

- Topul celor mai mari banci din Romania dupa valoarea activelor in 2018

- Topul bancilor dupa active in 2017

Asociatia Romana a Bancilor (ARB)

- Băncile din România nu au majorat comisioanele aferente operațiunilor în numerar

- Concurs de educatie financiara pentru elevi, cu premii in bani

- Creditele acordate de banci au crescut cu 14% in 2022

- Romanii stiu educatie financiara de nota 7

- Gradul de incluziune financiara in Romania a ajuns la aproape 70%

ROBOR

- ROBOR: ce este, cum se calculeaza, ce il influenteaza, explicat de Asociatia Pietelor Financiare

- ROBOR a scazut la 1,59%, dupa ce BNR a redus dobanda la 1,25%

- Dobanzile variabile la creditele noi in lei nu scad, pentru ca IRCC ramane aproape neschimbat, la 2,4%, desi ROBOR s-a micsorat cu un punct, la 2,2%

- IRCC, indicele de dobanda pentru creditele in lei ale persoanelor fizice, a scazut la 1,75%, dar nu va avea efecte imediate pe piata creditarii

- Istoricul ROBOR la 3 luni, in perioada 01.08.1995 - 31.12.2019

Taxa bancara

- Normele metodologice pentru aplicarea taxei bancare, publicate de Ministerul Finantelor

- Noul ROBOR se va aplica automat la creditele noi si prin refinantare la cele in derulare

- Taxa bancara ar putea fi redusa de la 1,2% la 0,4% la bancile mari si 0,2% la cele mici, insa bancherii avertizeaza ca indiferent de nivelul acesteia, intermedierea financiara va scadea iar dobanzile vor creste

- Raiffeisen anunta ca activitatea bancii a incetinit substantial din cauza taxei bancare; strategia va fi reevaluata, nu vor mai fi acordate credite cu dobanzi mici

- Tariceanu anunta un acord de principiu privind taxa bancara: ROBOR-ul ar putea fi inlocuit cu marja de dobanda a bancilor

Statistici BNR

- Deficitul contului curent, creștere cu 16% în ianuarie 2025

- Deficitul contului curent, aproape 30 miliarde euro în 2024

- Deficitul contului curent, aproape 20 miliarde euro după primele nouă luni

- Deficitul contului curent, aproape 18 miliarde euro după primele opt luni

- Deficitul contului curent, peste 9 miliarde euro pe primele cinci luni

Legislatie

- Decizia nr.105/2007 privind raportarea la Biroul de Credit

- Legea nr. 311/2015 privind schemele de garantare a depozitelor şi Fondul de garantare a depozitelor bancare

- Rambursarea anticipata a unui credit, conform OUG 50/2010

- OUG nr.21 din 1992 privind protectia consumatorului, actualizata

- Legea nr. 190 din 1999 privind creditul ipotecar pentru investiții imobiliare

Lege plafonare dobanzi credite

- Care este dobanda maxima la un credit IFN?

- BNR propune Parlamentului plafonarea dobanzilor la creditele bancilor intre 1,5 si 4 ori peste DAE medie, in functie de tipul creditului; in cazul IFN-urilor, plafonarea dobanzilor nu se justifica

- Legile privind plafonarea dobanzilor la credite si a datoriilor preluate de firmele de recuperare se discuta in Parlament (actualizat)

- Legea privind plafonarea dobanzilor la credite nu a fost inclusa pe ordinea de zi a comisiilor din Camera Deputatilor

- Senatorul Zamfir, despre plafonarea dobanzilor la credite: numai bou-i consecvent!

Anunturi banci

- BCR este inchisa vineri, 18 aprilie, si luni, 21 aprilie

- Cererile de transfer de bani prin Whatsapp, Telegram, Messenger sunt fraude

- Un telefon sau mesaj care pare de la banca poate fi frauda

- Cererea unui ajutor in bani poate fi o inselaciune

- Cate reclamatii primeste Intesa Sanpaolo Bank si cum le gestioneaza

Analize economice

- Inflația anuală, redusă la 4,86%

- Comerțul, a cincea lună consecutivă de ajustare a creșterii

- Pensia reală a crescut cu peste 15% anul trecut

- Deficitul bugetar, rezultat slab după primele două luni

- Deficit comercial în creștere cu 38,5% pe ianuarie 2025

Ministerul Finantelor

- Deficitul bugetar, din ce în ce mai mare la început de an

- -8,65% din PIB, deficit bugetar pe anul 2024

- Datoria publică, 51,4% din PIB la mijlocul anului

- Deficit bugetar de 3,6% din PIB după prima jumătate a anului

- Deficit bugetar de 3,4% din PIB după primele cinci luni ale anului

Biroul de Credit

- FUNDAMENTAREA LEGALITATII PRELUCRARII DATELOR PERSONALE IN SISTEMUL BIROULUI DE CREDIT

- BCR: prelucrarea datelor personale la Biroul de Credit

- Care banci si IFN-uri raporteaza clientii la Biroul de Credit

- Ce trebuie sa stim despre Biroul de Credit

- Care este procedura BCR de raportare a clientilor la Biroul de Credit

Procese

- ANPC pierde un proces cu Intesa si ARB privind modul de calcul al ratelor la credite

- Un client Credius obtine in justitie anularea creditului, din cauza dobanzii prea mari

- Hotararea judecatoriei prin care Aedificium, fosta Raiffeisen Banca pentru Locuinte, si statul sunt obligati sa achite unui client prima de stat

- Decizia Curtii de Apel Bucuresti in procesul dintre Raiffeisen Banca pentru Locuinte si Curtea de Conturi

- Vodafone, obligata de judecatori sa despagubeasca un abonat caruia a refuzat sa-i repare un telefon stricat sau sa-i dea banii inapoi (decizia instantei)

Stiri economice

- Deficitul comercial pe primele două luni ale anului, majorat cu 35%

- România, campioana europeană la șomajul tinerilor

- România, pe locul trei în UE la creșterea costului salarial în T4 2024

- Producția industrială, scădere conjuncturală în ianuarie 2025

- Datoria publică, 54,6% din PIB la finele lui 2024

Statistici

- România, marginal peste Estonia la inflația anuală

- România, a doua țară din UE ca pondere a salariaților cu venituri mici

- România, pe locul trei în UE la creșterea costului muncii în T2 2024

- Cheltuielile cu pensiile - România, pe locul 19 în UE ca pondere în PIB

- Dobanda din Cehia a crescut cu 7 puncte intr-un singur an

FNGCIMM

- Programul IMM Invest continua si in 2021

- Garantiile de stat pentru credite acordate de FNGCIMM au crescut cu 185% in 2020

- Programul IMM invest se prelungeste pana in 30 iunie 2021

- Firmele pot obtine credite bancare garantate si subventionate de stat, pe baza facturilor (factoring), prin programul IMM Factor

- Programul IMM Leasing va fi operational in perioada urmatoare, anunta FNGCIMM

Calculator de credite

- ROBOR la 3 luni a scazut cu aproape un punct, dupa masurile luate de BNR; cu cat se reduce rata la credite?

- In ce mall din sectorul 4 pot face o simulare pentru o refinantare?

Noutati BCE

- Dobanda la euro scade la 2,25%

- Acord intre BCE si BNR pentru supravegherea bancilor

- Banca Centrala Europeana (BCE) explica de ce a majorat dobanda la 2%

- BCE creste dobanda la 2%, dupa ce inflatia a ajuns la 10%

- Dobânda pe termen lung a continuat să scadă in septembrie 2022. Ecartul față de Polonia și Cehia, redus semnificativ

Noutati EBA

- Bancile romanesti detin cele mai multe titluri de stat din Europa

- Guidelines on legislative and non-legislative moratoria on loan repayments applied in the light of the COVID-19 crisis

- The EBA reactivates its Guidelines on legislative and non-legislative moratoria

- EBA publishes 2018 EU-wide stress test results

- EBA launches 2018 EU-wide transparency exercise

Noutati FGDB

- Banii din banci sunt garantati, anunta FGDB

- Depozitele bancare garantate de FGDB au crescut cu 13 miliarde lei

- Depozitele bancare garantate de FGDB reprezinta doua treimi din totalul depozitelor din bancile romanesti

- Peste 80% din depozitele bancare sunt garantate

- Depozitele bancare nu intra in campania electorala

CSALB

- Sistemul bancar romanesc este deosebit de bine pregatit pentru orice fel de socuri

- La CSALB poti castiga un litigiu cu banca pe care l-ai pierde in instanta

- Negocierile dintre banci si clienti la CSALB, in crestere cu 30%

- Sondaj: dobanda fixa la credite, considerata mai buna decat cea variabila, desi este mai mare

- CSALB: Romanii cu credite caută soluții pentru reducerea ratelor. Cum raspund bancile

First Bank

- Ce trebuie sa faca cei care au asigurare la credit emisa de Euroins

- First Bank este reprezentanta Eurobank in Romania: ce se intampla cu creditele Bancpost?

- Clientii First Bank pot face plati prin Google Pay

- First Bank anunta rezultatele financiare din prima jumatate a anului 2021

- First Bank are o noua aplicatie de mobile banking

Noutati FMI

- FMI: criza COVID-19 se transforma in criza economica si financiara in 2020, suntem pregatiti cu 1 trilion (o mie de miliarde) de dolari, pentru a ajuta tarile in dificultate; prioritatea sunt ajutoarele financiare pentru familiile si firmele vulnerabile

- FMI cere BNR sa intareasca politica monetara iar Guvernului sa modifice legea pensiilor

- FMI: majorarea salariilor din sectorul public si legea pensiilor ar trebui reevaluate

- IMF statement of the 2018 Article IV Mission to Romania

- Jaewoo Lee, new IMF mission chief for Romania and Bulgaria

Noutati BERD

- Creditele neperformante (npl) - statistici BERD

- BERD este ingrijorata de investigatia autoritatilor din Republica Moldova la Victoria Bank, subsidiara Bancii Transilvania

- BERD dezvaluie cat a platit pe actiunile Piraeus Bank

- ING Bank si BERD finanteaza parcul logistic CTPark Bucharest

- EBRD hails Moldova banking breakthrough

Noutati Federal Reserve

- Federal Reserve anunta noi masuri extinse pentru combaterea crizei COVID-19, care produce pagube "imense" in Statele Unite si in lume

- Federal Reserve urca dobanda la 2,25%

- Federal Reserve decided to maintain the target range for the federal funds rate at 1-1/2 to 1-3/4 percent

- Federal Reserve majoreaza dobanda de referinta pentru dolar la 1,5% - 1,75%

- Federal Reserve issues FOMC statement

Noutati BEI

- BEI a redus cu 31% sprijinul acordat Romaniei in 2018

- Romania implements SME Initiative: EUR 580 m for Romanian businesses

- European Investment Bank (EIB) is lending EUR 20 million to Agricover Credit IFN

Mobile banking

- Comisioanele BRD pentru MyBRD Mobile, MyBRD Net, My BRD SMS

- Termeni si conditii contractuale ale serviciului You BRD

- Recomandari de securitate ale BRD pentru utilizatorii de internet/mobile banking

- CEC Bank - Ghid utilizare token sub forma de card bancar

- Cinci banci permit platile cu telefonul mobil prin Google Pay

Noutati Comisia Europeana

- Avertismentul Comitetului European pentru risc sistemic (CERS) privind vulnerabilitățile din sistemul financiar al Uniunii

- Cele mai mici preturi din Europa sunt in Romania

- State aid: Commission refers Romania to Court for failure to recover illegal aid worth up to €92 million

- Comisia Europeana publica raportul privind progresele inregistrate de Romania in cadrul mecanismului de cooperare si de verificare (MCV)

- Infringements: Commission refers Greece, Ireland and Romania to the Court of Justice for not implementing anti-money laundering rules

Noutati BVB

- BET AeRO, primul indice pentru piata AeRO, la BVB

- Laptaria cu Caimac s-a listat pe piata AeRO a BVB

- Banca Transilvania plateste un dividend brut pe actiune de 0,17 lei din profitul pe 2018

- Obligatiunile Bancii Transilvania se tranzactioneaza la Bursa de Valori Bucuresti

- Obligatiunile Good Pople SA (FRU21) au debutat pe piata AeRO

Institutul National de Statistica

- România, la 78% din PIB-ul mediu pe locuitor al UE

- Producția industrială, la cota -1,8% după 11 luni din 2024

- Deficitul contului curent, peste 26 miliarde euro în noiembrie 2024

- Comerțul cu amănuntul - în creștere cu 8% pe primele 10 luni

- Deficitul balanței comerciale la 9 luni, cu 15% mai mare față de aceeași perioadă a anului trecut

Informatii utile asigurari

- Data de la care FGA face plati pentru asigurarile RCA Euroins: 17 mai 2023

- Asigurarea împotriva dezastrelor, valabilă și in caz de faliment

- Asiguratii nu au nevoie de documente de confirmare a cutremurului

- Cum functioneaza o asigurare de viata Metropolitan pentru un credit la Banca Transilvania?

- Care sunt documente necesare pentru dosarul de dauna la Cardif?

ING Bank

- La ING se vor putea face plati instant din decembrie 2022

- Cum evitam tentativele de frauda online?

- Clientii ING Bank trebuie sa-si actualizeze aplicatia Home Bank pana in 20 martie

- Obligatiunile Rockcastle, cel mai mare proprietar de centre comerciale din Europa Centrala si de Est, intermediata de ING Bank

- ING Bank transforma departamentul de responsabilitate sociala intr-unul de sustenabilitate