Mario Draghi: The euro: from the past to the future

Autor: Bancherul.ro

Autor: Bancherul.ro

2011-04-30 12:48

Mario Draghi, the Governor of the Bank of Italy, spoke on 21.03.2011 at the Università del Sacro Cuore in Milan, giving an address entitled "The euro: from the past to the future":

The euro: an idea that goes back a long way

The idea of a single currency, in place of a congeries of local or national monies, did not gain much ground in modern Europe until the second half of the nineteenth century. Why was that? It would be natural to think that a universal currency is a timeless aspiration: to extend the traditional functions and therefore the advantages of money in the widest geographical sphere.

A possible explanation is the redistributive use that money had been put to over the centuries: in classical antiquity and then in the Middle Ages, adjusting the currency – increasing or reducing the gold or silver content of metal coins – was often a way for the prince to appropriate resources; striking coins was an attribute of sovereignty. It took a long time to reach the point, in the nineteenth century, when the value of a monetary unit was defined solely by the quantity of precious metal it contained; paper money was declared convertible into metal; money had been “depoliticized”.

Thinking up monetary unions then became a possible exercise, as long as the candidates had the same standard: gold, silver or bimetallic; it was sufficient to agree on the fineness, the weight and the denomination of the coins to be put into circulation. A union of this kind, the Latin Monetary Union, inaugurated in 1865, brought together Italy, France, Switzerland, Belgium and Greece, but it had a difficult life and broke up, as a practical matter, at the beginning of the next century. The monetary unions realized within federal states – the Swiss and the German ones – fared better.

But the use of the currency for redistributing wealth did not come to an end. Despite the establishment and consolidation of technical institutions – the central banks – delegated to manage the issuance and circulation of money, the currency reverted, at least in wartime, to being an instrument of state financing. The transition to paper money facilitated this process. During the First World War, the Governor of the Bank of Italy, Bonaldo Stringher, noted that the Bank of Italy “has given a stimulus to banknote production equal to that received by the machine shops producing bullets”.1 Banca d’Italia, Adunanza generale ordinaria degli azionisti, year 1918, p. 49 (only in Italian).

In the 1920s and 1930s, marked by the Great Depression, the monetary instrument was returned, with the contribution of Keynes, to the toolkit of economic policy. The potential of this instrument prompted the central banks and the governments that controlled them to make ample use of it to manage the economic cycle but also as a means of more or less openly supporting the public finances. The height of this era was reached in the 1970s, a decade of high inflation. In Europe the Bundesbank basically protected the German economy from these excesses. There ensued a reconsideration of the role of the central banks and the objectives and instruments of monetary policy, whose findings would be used extensively in the period that followed right up to today.

In the 1950s the ruinous effects of the Second World War spurred a revival of interest in integration among the European economies, which would simultaneously be a means of promoting growth and ensuring peace.

The creation of the European Common Market accompanied the period of the fastest economic growth ever experienced on the Continent. To buttress these results and, almost in a utopian spirit in the midst of international monetary disorder, plans were made for the single currency.

The 1970 Werner Report was the first official plan for European monetary union and, while it was never implemented, it paved the way twenty years later for the Delors Report, which, basing itself on the still limited experience of monetary cooperation realized in the meantime (the “snake” of the 1970s and the European Monetary System of the 1980s), planned the creation of the euro. This was made possible by an altered cultural climate, which viewed the independence of the central banks and price stability as the fundamental values upon which to base a sound currency.

The plan was propelled by personalities from a generation that harboured the memory of the ruins of war: Andreotti, Ciampi, Delors, Giscard d’Estaing, Kohl, Mitterrand and Schmidt, who were flanked by figures from the next generation, like Tommaso Padoa-Schioppa.

The Maastricht Treaty of 1992 created the institutions of modern monetary Europe, establishing the passage of monetary sovereignty to the European System of Central Banks. The System’s objective was defined clearly and with legislation having constitutional status – taking a leaf from the German experience – as maintaining price stability, a value that became the common heritage of all citizens of the area. From this followed the basic principle that governments must not interfere in monetary policy; monetary financing of states was prohibited.

The euro has been with us since 1999 and, as an actually circulating currency, since 2002.

To achieve this outcome, in many countries major political obstacles had to be surmounted. In Italy, it was necessary to overcome society’s inurement to devaluations and inflation. There was no lack of academic scepticism, including from the other side of the Atlantic. There were doubts about the European economies ever being able to constitute an optimal currency area in Mundell’s terms.

The European monetary construction works. The euro is not in question.

The first twelve years of the euro

Today the euro is the second most important currency in the world: it accounts for 27 per cent of global currency reserves; before the Union, the currencies replaced by the euro together accounted for 18 per cent.

Between 1998 and 2010 the total value of imports and exports of goods within the euro area rose from 27 to 32 per cent of GDP. The greater volume of internal trade was not at the expense of that with the rest of the world, which recorded an even sharper increase, from 25 to 33 per cent, driven by the expansion of the emerging economies, more and more open to world trade.

Integrated infrastructures were created for payments in the area: for wholesale and retail payments and, in the near future, for the settlement of securities transactions. Between 1999 and 2008 the average daily volume of cross-border payments between euro-area countries via TARGET increased by almost 250 per cent; the average total volume of transactions, which includes domestic payments, grew by more than 120 per cent – more than four times greater than the growth recorded by the equivalent infrastructure in the United States.

Price stability is inscribed in the conduct of economic agents, even in countries which were previously the most inflationary, enhancing the legacy of the best traditions of the participating central banks. In the twelve years of the euro, annual inflation in the area has averaged just under 2 per cent, fully in line with the definition of price stability adopted by the Governing Council of the European Central Bank (ECB). It has fallen by more than one half compared with the previous two decades; the reduction was greater than that seen in the United States in the same period. In Italy, the average annual increase in consumer prices was five percentage points lower than in the twenty-year period preceding the introduction of the euro.

Today exogenous price shocks have modest repercussions on the euro-area economies: the increases in oil prices between 2007 and 2008 were comparable, in real terms, to those at the end of the 1970s, but they generated a one-off rise in consumer prices of less than two percentage points, which did not take hold in inflation, in contrast to what happened in the past in several countries in the area. According to our estimates, the inflationary effect in Italy of a shock of this kind has been reduced to one tenth of what it was in the 1970s. Of course, structural changes in production processes have played a part, but the credibility earned by monetary policy and the resulting changes in price and wage setting have played a crucial role.

Price stability and low risk premiums lead to low nominal and real interest rates, thereby fostering economic growth. From the introduction of the euro to today, the real three-month interest rate in Italy has averaged 1 per cent, four percentage points lower than in the previous decade; the average nominal rate on bank loans for house purchases and that on short-term loans to non-financial firms have averaged 4.5 and 5.5 per cent respectively, compared with 11.3 and 12.6 per cent in the ten previous years. It is surely not the monetary conditions that are responsible for the growth difficulties of the Italian economy.

Again with reference to the twelve years of the euro, annual expenditure for interest payments on Italy’s public debt averaged 5.3 per cent of GDP, against 11.5 per cent in the first half of the 1990s and 7.5 per cent in the 1980s. It is still the case today that, despite strong pressures on the government securities markets of some of the countries of the area, the yields on Italian ten-year securities are in line with the averages recorded in the last decade.

The response of euro-area monetary policy to the global crisis of the last three years was rapid and decisive. Inflation expectations held firm even at the height of the crisis, allowing us to take action to keep the markets working, support lending and avert the collapse of the economy.

Money market rates were reduced to close to zero; exceptional liquidity creation measures were adopted.

Without the Union, simply coordinating national decisions would not have produced such rapid and effective results. Some countries, including our own, could have been overcome by the crisis.

But the credibility we have earned will not necessarily last for ever; we have to remain vigilant in safeguarding price stability. The culture of stability must also be extended to other fields: to fiscal policy, to structural reform where weaknesses have emerged in the European construction, as they did clearly during the recent sovereign debt crisis.

The sovereign debt crisis of some euro-area countries

The strains spread outwards from Greece, where they had been generated by the disorder of that country’s public finances, and hit the Irish and Portuguese government securities markets last spring. Spanish and Italian government bonds have also seen their yield spreads widen with respect to the corresponding German securities.

The response of the European institutions and governments has followed a rough path.

The financial support plan for Greece, agreed at the beginning of May 2010 by the euro-area countries with the European Commission and the IMF, did not eliminate the tensions, which, on the contrary, spread to the stock, bond and interbank markets.

To contain the contagion risk posed to other countries, several days later the EU Council instituted a financial stabilization arrangement under which the countries of the area could get a loan at analogous conditions to those applied by the IMF in similar circumstances. It was decided that the bulk of the resources would come from the European Financial Stability Facility (EFSF), a new body authorized to fund itself on the market by issuing securities guaranteed by the countries of the euro area. In the same days a number of countries adopted or announced drastic plans for the consolidation of public finances.

In the same month of May 2010, the Governing Council of the ECB came to the conclusion that the tensions in the markets were compromising the monetary policy transmission mechanism. It launched the Securities Markets Programme of purchases of public securities issued by euro-area countries with a view to supporting market segments hit especially hard by the crisis; and it confirmed its commitment to supply abundant liquidity to the system. This did not imply the monetary financing of sovereign states or the creation of liquidity; the interventions were temporary and sterilized.

This set of measures stemmed the tensions, which nevertheless began to intensify again during the summer and even more in the final part of the year, once more affecting not only Greek bonds but those of Portugal and especially of Ireland, which had issued a government guarantee for all bank liabilities. At the end of November the EU finance ministers approved a plan of financial support for Ireland.

This measure too helped to allay but did not eliminate the tensions, in a context of elevated uncertainty in the markets regarding the prospects of stabilization in the countries hit by the crisis and the possible interconnections between sovereign risks and the vulnerability of some banking systems.

The crisis originates from imbalances that in some countries concern the public finances, in others the banking system. Overcoming the difficulties first requires drastic, resolute national measures.

The stance of monetary policy has been expansionary for a long time: since May 2009 the Eurosystem’s reference interest rate has held at 1 per cent, an exceptionally low level; real short-term rates have remained negative by a wide margin even after the start of the cyclical recovery.

The emergence of inflationary pressure calls for a careful evaluation of the timetable and manner in which to proceed with a normalization of monetary conditions. A deterioration of expectations must be prevented, to keep the impulse originating from international prices from being transmitted to domestic prices and wages and thereby influencing inflation beyond the short term. As President Trichet recalled on the occasion of the meeting at the beginning of March, the Governing Council of the ECB remains prepared to act in a firm and timely manner to ensure that these risks do not materialize.

We are following the tragic events in Japan with the closest and most heartfelt attention. The exchange rate interventions agreed on 18 March by the finance ministers and central bank governors of the G7 countries are intended to prevent excessive volatility of exchange rates from having adverse effects on economic and financial stability.

A construction to be strengthened

The sovereign debt crisis has brought to light at least two factors of fragility in European construction.

In the first place, the rules did not avert imprudent fiscal policies in some countries, which were either unable or unwilling to exploit the positive phases of the economic cycle in order to consolidate their public finances. Each country was given a specific medium-term objective for the budget position, agreed at European level: a position in balance or surplus, depending on its specific sensitivity to the economic cycle and to interest rates; the objective was subject to review in the light of long-term factors such as population ageing and the debt level. In addition, the countries whose public debt exceeded 60 per cent of GDP had to reduce it “at a satisfactory pace”. When the global crisis came, many countries were still far from achieving those objectives.

Second, the system of multilateral surveillance did not prevent pronounced macroeconomic imbalances: productivity differentials, current account deficits, excessive private sector borrowing. In 2009, the deficit on the current account of the balance of payments amounted to 10 per cent in Greece and 7.5 per cent in Portugal. In Ireland, Portugal and Spain, the financial debt of households and firms amounted to between one and a half and two times the euro-area average of 170 per cent of GDP (in Italy it was equal to 130 per cent). In Ireland, the largest national banks had balance-sheet assets totalling more than five times GDP; the collapse of property prices and the recession caused them huge losses.

Imbalances of this kind ultimately have repercussions on the public finances, even in countries where these are initially in order. In the Irish case, the public resources spent on supporting the banks came to more than 20 per cent of GDP.

Last autumn the European Commission and the working group led by European Council President Herman Van Rompuy put forward proposals concerning both aspects: how to make the Stability and Growth Pact more cogent; how to extend surveillance to macroeconomic developments.

It was proposed that the Pact be strengthened for the prevention of fiscal imbalances, by intensifying monitoring and introducing timely monetary sanctions, and for their adjustment, by providing in particular for the possibility of initiating the excessive-deficit procedure not only when the deficit exceeds 3 per cent of GDP but also when the reduction in the debt towards the 60 per cent ceiling is deemed unsatisfactory.

In the macroeconomic field, a system of monitoring imbalances having potentially significant implications for the euro area’s financial stability was envisaged, with quantitative indicators and critical thresholds based on which the European Council may issue recommendations to the country concerned and, in the most serious cases, apply financial sanctions.

Lastly, it was recommended that the EFSF be replaced from 2013 onwards by a permanent mechanism of financial support, the European Stability Mechanism (ESM). Only the countries considered to be solvent would have access to financing, which would be conditional in any case on their adopting serious adjustment plans; the others would be asked to negotiate a debt restructuring plan with private creditors by which to return to a situation of solvency.

On 15 March the EU finance ministers agreed a “general approach” that fully implements the recommendations of the Commission and of the Van Rompuy working group. In particular, they approved the proposal to introduce a numerical rule – one twentieth of the debt-to-GDP ratio in excess of the 60 per cent ceiling – for the annual reduction of the debt.

Several days earlier the Heads of State and Government of the euro area had increased the effective lending capacity of the EFSF to €440 billion and set that of the future ESM at €500 billion; they also decided that in exceptional circumstances both the Fund and the Mechanism could purchase euro-area countries’ government securities on the primary market.

The pact for the euro, with all these measures, widens the focus of attention to include macroeconomic imbalances, strengthens budget discipline in the area, and improves the mechanism of support for countries that get into financial difficulty. This was a necessary step to avoid dangerously sapping the Community spirit that is the lifeblood of the euro.

The measures are based on correct principles. The technical and negotiating effort involved has been substantial; the results are encouraging but not yet sufficient. Discussion of the pact will continue in policymaking fora; deficiencies or points that are hazy can be corrected.

Fiscal policy surveillance needs to rely on more automatic procedures that limit the politicization of public accounting as far as possible and avert possible collusive conduct between countries. Several other aspects of this complex reform of European governance still require attention and work. It is necessary, for example, to determine with precision all the “relevant factors” to be considered in assessing the adequacy of the pace of public debt reduction; to identify the set of indicators serving to signal a situation of macroeconomic imbalance and the related critical thresholds; and to establish the criteria for evaluating a country’s solvency.

Concerning structural policies to boost potential output and competitiveness, the pact, for the time being, relies on procedures based on peer pressure, which in the case of the Lisbon strategy have not worked. The commitment of the national governments remains central.

We must not forget a golden rule: increasing the economy’s growth potential and consolidating the public budget are national priorities first of all. Governments should pursue them even independently of the European rules, for the good of their peoples, and should do so with special commitment in the countries farthest from these objectives.

Italy’s situation

Between 2008 and 2009, with the global crisis in full swing, Italy’s budget deficit rose from 2.7 to 5.4 per cent of GDP; discretionary policies did not contribute to the increase.

( See Britta Hamburg, Sandro Momigliano, Bernhard Manzke and Stefano Siviero, “The Reaction of Fiscal Policy to the Crisis in Italy and Germany: Are They Really Polar Cases in the European Context”, forthcoming in Fiscal Policy: Lessons from the Crisis, proceedings of the Twelfth Workshop on Public Finances, Perugia, 25-27 March 2010. )

The deficit of the euro area as a whole more than tripled, rising to 6.3 per cent. In 2010 the deficit declined to 4.6 per cent in Italy, while in the euro area it remained unchanged according to European Commission estimates. The Government’s management of the accounts was facilitated by the fact that the solidity of the Italian banking system did not require significant aid to be charged to the public budget.

Italy’s public debt, already very high, rose again. Its management was prudent; the average residual maturity was lengthened progressively, notwithstanding a context that remained uncertain and volatile.

The financial condition of firms and households is solid on the whole. Savers’ propensity to invest in high-risk financial instruments is low; debt is limited, although it is concentrated in variable-rate liabilities, which are inherently riskier.

The Italian economy’s problem – it is well worth recalling – is the structural difficulty of growth. The arduous task of economic policy is to change this situation while at the same time reducing the ratio of public debt to GDP. To rebuild a solid primary surplus rapidly and not to elude the need to take measures that structurally support growth: this is the challenge.

Raising the tax rates is out of the question: it would jeopardize the objective of growth and penalize honest taxpayers unbearably; indeed, the rates ought to be gradually lowered as headway is made in reducing tax evasion and avoidance. The only option is to control spending, but with a selective approach that distinguishes between what fosters growth and what impedes it. Wise political choices must necessarily be based on a detailed assessment of the effects, including the macroeconomic effects, of every expenditure item.

The more attentive multilateral surveillance of the sustainability of public budgets envisaged by the new pact is not to be feared; it can help us. The reforms already carried out, especially the pension reform, put us among the countries that require a smaller correction of budget balances to ensure long-run stability.

The new European rule for debt reduction would not be a much tighter constraint for us than the one already imposed by the existing rule on structural budget balance. It is estimated that achieving structural budget balance would also ensure, ipso facto, compliance with the rule on debt under favourable scenarios of economic growth.

( See Ignazio Visco, “La governance economica europea: riforma e implicazioni”, Remarks delivered at the University of l’Aquila for the twentieth anniversary of the Economics Faculty, 8 March 2011 (only in Italian).

Seventeen sovereign countries that share a single currency form a reality without precedent in history. The euro is a bold intellectual construction, a courageous and farsighted political project. It was, and remains, a prerequisite for economic wellbeing.

The President of the Republic, in his address to Parliament on 17 March, called European integration “an extraordinary historical invention in which Italy has successfully played a leading role since the 1950s.”

One hundred and fifty years ago we Italians undertook an equally important construction: our country’s monetary unification, which would then consolidate the political unification just attained.

These two historical events are joined in an ideal continuity. For us, the present and the future of the euro are also the continuation of our own long history.

Comentarii

Adauga un comentariu

Adauga un comentariu folosind contul de Facebook

Alte stiri din categoria: Noutati BCE

Banca Centrala Europeana (BCE) explica de ce a majorat dobanda la 2%

Banca Centrala Europeana (BCE) explica de ce a majorat dobanda la 2%, in cadrul unei conferinte de presa sustinute de Christine Lagarde, președinta BCE, si Luis de Guindos, vicepreședintele BCE. Iata textul publicat de BCE: DECLARAȚIE DE POLITICĂ MONETARĂ detalii

BCE creste dobanda la 2%, dupa ce inflatia a ajuns la 10%

Banca Centrala Europeana (BCE) a majorat dobanda de referinta pentru tarile din zona euro cu 0,75 puncte, la 2% pe an, din cauza cresterii substantiale a inflatiei, ajunsa la aproape 10% in septembrie, cu mult peste tinta BCE, de doar 2%. In aceste conditii, BCE a anuntat ca va continua sa majoreze dobanda de politica monetara. De asemenea, BCE a luat masuri pentru a reduce nivelul imprumuturilor acordate bancilor in perioada pandemiei coronavirusului, prin majorarea dobanzii aferente acestor facilitati, denumite operațiuni țintite de refinanțare pe termen mai lung (OTRTL). Comunicatul BCE Consiliul guvernatorilor a decis astăzi să majoreze cu 75 puncte de bază cele trei rate ale dobânzilor detalii

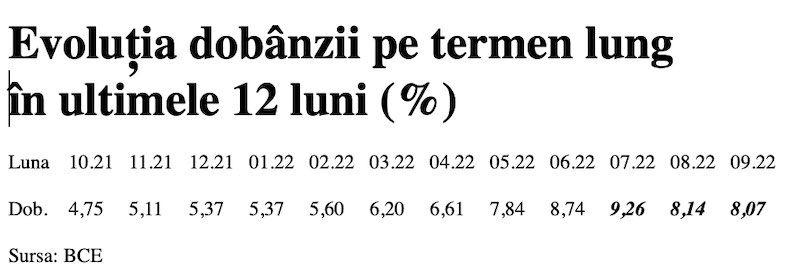

Dobânda pe termen lung a continuat să scadă in septembrie 2022. Ecartul față de Polonia și Cehia, redus semnificativ

Dobânda pe termen lung pentru România a scăzut în septembrie 2022 la valoarea medie de 8,07%, potrivit datelor publicate de Banca Centrală Europeană. Acest indicator, cu referința la un termen de 10 ani (10Y), a continuat astfel tendința detalii

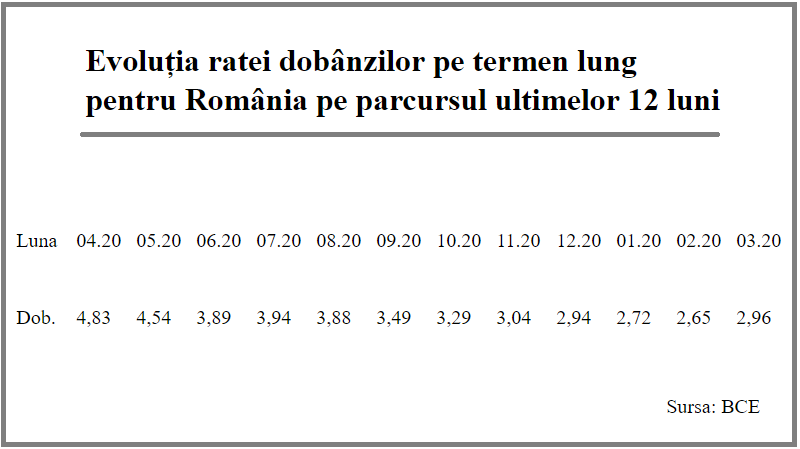

Rata dobanzii pe termen lung pentru Romania, in crestere la 2,96%

Rata dobânzii pe termen lung pentru România a crescut la 2,96% în luna martie 2021, de la 2,65% în luna precedentă, potrivit datelor publicate de Banca Centrală Europeană. Acest indicator critic pentru plățile la datoria externă scăzuse anterior timp de șapte luni detalii

- BCE recomanda bancilor sa nu plateasca dividende

- Modul de functionare a relaxarii cantitative (quantitative easing – QE)

- Dobanda la euro nu va creste pana in iunie 2020

- BCE trebuie sa fie consultata inainte de adoptarea de legi care afecteaza bancile nationale

- BCE a publicat avizul privind taxa bancara

- BCE va mentine la 0% dobanda de referinta pentru euro cel putin pana la finalul lui 2019

- ECB: Insights into the digital transformation of the retail payments ecosystem

- ECB introductory statement on Governing Council decisions

- Speech by Mario Draghi, President of the ECB: Sustaining openness in a dynamic global economy

- Deciziile de politica monetara ale BCE

Criza COVID-19

- In majoritatea unitatilor BRD se poate intra fara certificat verde

- La BCR se poate intra fara certificat verde

- Firmele, obligate sa dea zile libere parintilor care stau cu copiii in timpul pandemiei de coronavirus

- CEC Bank: accesul in banca se face fara certificat verde

- Cum se amana ratele la creditele Garanti BBVA

Topuri Banci

- Topul bancilor dupa active si cota de piata in perioada 2022-2015

- Topul bancilor cu cele mai mici dobanzi la creditele de nevoi personale

- Topul bancilor la active in 2019

- Topul celor mai mari banci din Romania dupa valoarea activelor in 2018

- Topul bancilor dupa active in 2017

Asociatia Romana a Bancilor (ARB)

- Băncile din România nu au majorat comisioanele aferente operațiunilor în numerar

- Concurs de educatie financiara pentru elevi, cu premii in bani

- Creditele acordate de banci au crescut cu 14% in 2022

- Romanii stiu educatie financiara de nota 7

- Gradul de incluziune financiara in Romania a ajuns la aproape 70%

ROBOR

- ROBOR: ce este, cum se calculeaza, ce il influenteaza, explicat de Asociatia Pietelor Financiare

- ROBOR a scazut la 1,59%, dupa ce BNR a redus dobanda la 1,25%

- Dobanzile variabile la creditele noi in lei nu scad, pentru ca IRCC ramane aproape neschimbat, la 2,4%, desi ROBOR s-a micsorat cu un punct, la 2,2%

- IRCC, indicele de dobanda pentru creditele in lei ale persoanelor fizice, a scazut la 1,75%, dar nu va avea efecte imediate pe piata creditarii

- Istoricul ROBOR la 3 luni, in perioada 01.08.1995 - 31.12.2019

Taxa bancara

- Normele metodologice pentru aplicarea taxei bancare, publicate de Ministerul Finantelor

- Noul ROBOR se va aplica automat la creditele noi si prin refinantare la cele in derulare

- Taxa bancara ar putea fi redusa de la 1,2% la 0,4% la bancile mari si 0,2% la cele mici, insa bancherii avertizeaza ca indiferent de nivelul acesteia, intermedierea financiara va scadea iar dobanzile vor creste

- Raiffeisen anunta ca activitatea bancii a incetinit substantial din cauza taxei bancare; strategia va fi reevaluata, nu vor mai fi acordate credite cu dobanzi mici

- Tariceanu anunta un acord de principiu privind taxa bancara: ROBOR-ul ar putea fi inlocuit cu marja de dobanda a bancilor

Statistici BNR

- Deficitul contului curent după primele două luni, mai mare cu 25%

- Deficitul contului curent, -0,39% din PIB după prima lună a anului

- Deficitul contului curent, redus cu 17%

- Inflatia a încheiat anul 2023 la 6,61%, semnificativ sub prognoza oficială

- Deficitul contului curent, redus cu o cincime după primele zece luni ale anului

Legislatie

- Legea nr. 311/2015 privind schemele de garantare a depozitelor şi Fondul de garantare a depozitelor bancare

- Rambursarea anticipata a unui credit, conform OUG 50/2010

- OUG nr.21 din 1992 privind protectia consumatorului, actualizata

- Legea nr. 190 din 1999 privind creditul ipotecar pentru investiții imobiliare

- Reguli privind stabilirea ratelor de referinţă ROBID şi ROBOR

Lege plafonare dobanzi credite

- BNR propune Parlamentului plafonarea dobanzilor la creditele bancilor intre 1,5 si 4 ori peste DAE medie, in functie de tipul creditului; in cazul IFN-urilor, plafonarea dobanzilor nu se justifica

- Legile privind plafonarea dobanzilor la credite si a datoriilor preluate de firmele de recuperare se discuta in Parlament (actualizat)

- Legea privind plafonarea dobanzilor la credite nu a fost inclusa pe ordinea de zi a comisiilor din Camera Deputatilor

- Senatorul Zamfir, despre plafonarea dobanzilor la credite: numai bou-i consecvent!

- Parlamentul dezbate marti legile de plafonare a dobanzilor la credite si a datoriilor cesionate de banci firmelor de recuperare (actualizat)

Anunturi banci

- Bancile comunica automat cu ANAF situatia popririlor

- BRD bate recordul la credite de consum, in ciuda dobanzilor mari, si obtine un profit ridicat

- CEC Bank a preluat Fondul de Garantare a Creditului Rural

- BCR aproba credite online prin aplicatia George, dar contractele se semneaza la banca

- Aplicatia Eximbank, indisponibila temporar

Analize economice

- România - prima în UE la inflație, prin efect de bază

- Deficitul comercial lunar a revenit peste cota de 2 miliarde euro

- România, 78% din media UE la PIB/locuitor în 2023

- România - prima în UE la inflație, prin efect de bază

- Inflația anuală, în scădere la 7,23%

Ministerul Finantelor

- Datoria publică, imediat sub pragul de 50% din PIB la începutul anului 2024

- Deficitul bugetar, deja -1,67% din PIB după primele două luni

- Datoria publică, sub pragul de 50% din PIB la finele anului 2023

- Deficitul bugetar, din ce în ce mai mare la început de an

- Deficitul bugetar după 8 luni, încă mai mare față de rezultatul din anul trecut

Biroul de Credit

- FUNDAMENTAREA LEGALITATII PRELUCRARII DATELOR PERSONALE IN SISTEMUL BIROULUI DE CREDIT

- BCR: prelucrarea datelor personale la Biroul de Credit

- Care banci si IFN-uri raporteaza clientii la Biroul de Credit

- Ce trebuie sa stim despre Biroul de Credit

- Care este procedura BCR de raportare a clientilor la Biroul de Credit

Procese

- Un client Credius obtine in justitie anularea creditului, din cauza dobanzii prea mari

- Hotararea judecatoriei prin care Aedificium, fosta Raiffeisen Banca pentru Locuinte, si statul sunt obligati sa achite unui client prima de stat

- Decizia Curtii de Apel Bucuresti in procesul dintre Raiffeisen Banca pentru Locuinte si Curtea de Conturi

- Vodafone, obligata de judecatori sa despagubeasca un abonat caruia a refuzat sa-i repare un telefon stricat sau sa-i dea banii inapoi (decizia instantei)

- Taxa de reziliere a abonamentului Vodafone inainte de termen este ilegala (decizia definitiva a judecatorilor)

Stiri economice

- Inflația anuală a revenit la nivelul de la finele anului anterior

- Pensia reală de asigurări sociale de stat a crescut anul trecut cu 2,9%

- Producția de cereale boabe pe 2023, cu o zecime mai mare față de anul precedent

- România, țara UE cu cea mai mare creștere a costului salarial

- Deficitul comercial în prima lună a anului, la cea mai mică valoare din septembrie 2021 încoace

Statistici

- Care este valoarea salariului minim brut si net pe economie in 2024?

- Cat va fi salariul brut si net in Romania in 2024, 2025, 2026 si 2027, conform prognozei oficiale

- România, pe ultimul loc în UE la evoluția productivității muncii în agricultură

- INS: Veniturile romanilor au crescut anul trecut cu 10%. Banii de mancare, redistribuiti cu precadere spre locuinta, transport si haine

- Inflatia anuala - 13,76% in aprilie 2022 si va ramane cu doua cifre pana la mijlocul anului viitor

FNGCIMM

- Programul IMM Invest continua si in 2021

- Garantiile de stat pentru credite acordate de FNGCIMM au crescut cu 185% in 2020

- Programul IMM invest se prelungeste pana in 30 iunie 2021

- Firmele pot obtine credite bancare garantate si subventionate de stat, pe baza facturilor (factoring), prin programul IMM Factor

- Programul IMM Leasing va fi operational in perioada urmatoare, anunta FNGCIMM

Calculator de credite

- ROBOR la 3 luni a scazut cu aproape un punct, dupa masurile luate de BNR; cu cat se reduce rata la credite?

- In ce mall din sectorul 4 pot face o simulare pentru o refinantare?

Noutati BCE

- Acord intre BCE si BNR pentru supravegherea bancilor

- Banca Centrala Europeana (BCE) explica de ce a majorat dobanda la 2%

- BCE creste dobanda la 2%, dupa ce inflatia a ajuns la 10%

- Dobânda pe termen lung a continuat să scadă in septembrie 2022. Ecartul față de Polonia și Cehia, redus semnificativ

- Rata dobanzii pe termen lung pentru Romania, in crestere la 2,96%

Noutati EBA

- Bancile romanesti detin cele mai multe titluri de stat din Europa

- Guidelines on legislative and non-legislative moratoria on loan repayments applied in the light of the COVID-19 crisis

- The EBA reactivates its Guidelines on legislative and non-legislative moratoria

- EBA publishes 2018 EU-wide stress test results

- EBA launches 2018 EU-wide transparency exercise

Noutati FGDB

- Banii din banci sunt garantati, anunta FGDB

- Depozitele bancare garantate de FGDB au crescut cu 13 miliarde lei

- Depozitele bancare garantate de FGDB reprezinta doua treimi din totalul depozitelor din bancile romanesti

- Peste 80% din depozitele bancare sunt garantate

- Depozitele bancare nu intra in campania electorala

CSALB

- La CSALB poti castiga un litigiu cu banca pe care l-ai pierde in instanta

- Negocierile dintre banci si clienti la CSALB, in crestere cu 30%

- Sondaj: dobanda fixa la credite, considerata mai buna decat cea variabila, desi este mai mare

- CSALB: Romanii cu credite caută soluții pentru reducerea ratelor. Cum raspund bancile

- O firma care a facut un schimb valutar gresit s-a inteles cu banca, prin intermediul CSALB

First Bank

- Ce trebuie sa faca cei care au asigurare la credit emisa de Euroins

- First Bank este reprezentanta Eurobank in Romania: ce se intampla cu creditele Bancpost?

- Clientii First Bank pot face plati prin Google Pay

- First Bank anunta rezultatele financiare din prima jumatate a anului 2021

- First Bank are o noua aplicatie de mobile banking

Noutati FMI

- FMI: criza COVID-19 se transforma in criza economica si financiara in 2020, suntem pregatiti cu 1 trilion (o mie de miliarde) de dolari, pentru a ajuta tarile in dificultate; prioritatea sunt ajutoarele financiare pentru familiile si firmele vulnerabile

- FMI cere BNR sa intareasca politica monetara iar Guvernului sa modifice legea pensiilor

- FMI: majorarea salariilor din sectorul public si legea pensiilor ar trebui reevaluate

- IMF statement of the 2018 Article IV Mission to Romania

- Jaewoo Lee, new IMF mission chief for Romania and Bulgaria

Noutati BERD

- Creditele neperformante (npl) - statistici BERD

- BERD este ingrijorata de investigatia autoritatilor din Republica Moldova la Victoria Bank, subsidiara Bancii Transilvania

- BERD dezvaluie cat a platit pe actiunile Piraeus Bank

- ING Bank si BERD finanteaza parcul logistic CTPark Bucharest

- EBRD hails Moldova banking breakthrough

Noutati Federal Reserve

- Federal Reserve anunta noi masuri extinse pentru combaterea crizei COVID-19, care produce pagube "imense" in Statele Unite si in lume

- Federal Reserve urca dobanda la 2,25%

- Federal Reserve decided to maintain the target range for the federal funds rate at 1-1/2 to 1-3/4 percent

- Federal Reserve majoreaza dobanda de referinta pentru dolar la 1,5% - 1,75%

- Federal Reserve issues FOMC statement

Noutati BEI

- BEI a redus cu 31% sprijinul acordat Romaniei in 2018

- Romania implements SME Initiative: EUR 580 m for Romanian businesses

- European Investment Bank (EIB) is lending EUR 20 million to Agricover Credit IFN

Mobile banking

- Comisioanele BRD pentru MyBRD Mobile, MyBRD Net, My BRD SMS

- Termeni si conditii contractuale ale serviciului You BRD

- Recomandari de securitate ale BRD pentru utilizatorii de internet/mobile banking

- CEC Bank - Ghid utilizare token sub forma de card bancar

- Cinci banci permit platile cu telefonul mobil prin Google Pay

Noutati Comisia Europeana

- Avertismentul Comitetului European pentru risc sistemic (CERS) privind vulnerabilitățile din sistemul financiar al Uniunii

- Cele mai mici preturi din Europa sunt in Romania

- State aid: Commission refers Romania to Court for failure to recover illegal aid worth up to €92 million

- Comisia Europeana publica raportul privind progresele inregistrate de Romania in cadrul mecanismului de cooperare si de verificare (MCV)

- Infringements: Commission refers Greece, Ireland and Romania to the Court of Justice for not implementing anti-money laundering rules

Noutati BVB

- BET AeRO, primul indice pentru piata AeRO, la BVB

- Laptaria cu Caimac s-a listat pe piata AeRO a BVB

- Banca Transilvania plateste un dividend brut pe actiune de 0,17 lei din profitul pe 2018

- Obligatiunile Bancii Transilvania se tranzactioneaza la Bursa de Valori Bucuresti

- Obligatiunile Good Pople SA (FRU21) au debutat pe piata AeRO

Institutul National de Statistica

- Comerțul cu amănuntul, în expansiune la început de an

- România, pe locul 2 în UE la creșterea comerțului cu amănuntul în ianuarie 2024

- Comerțul cu amănuntul, în creștere cu 1,9% pe anul 2023

- Comerțul cu amănuntul, în creștere pe final de an

- Comerțul cu amănuntul, stabilizat la +2% față de anul anterior

Informatii utile asigurari

- Data de la care FGA face plati pentru asigurarile RCA Euroins: 17 mai 2023

- Asigurarea împotriva dezastrelor, valabilă și in caz de faliment

- Asiguratii nu au nevoie de documente de confirmare a cutremurului

- Cum functioneaza o asigurare de viata Metropolitan pentru un credit la Banca Transilvania?

- Care sunt documente necesare pentru dosarul de dauna la Cardif?

ING Bank

- La ING se vor putea face plati instant din decembrie 2022

- Cum evitam tentativele de frauda online?

- Clientii ING Bank trebuie sa-si actualizeze aplicatia Home Bank pana in 20 martie

- Obligatiunile Rockcastle, cel mai mare proprietar de centre comerciale din Europa Centrala si de Est, intermediata de ING Bank

- ING Bank transforma departamentul de responsabilitate sociala intr-unul de sustenabilitate

Ultimele Comentarii

-

nevoia de banci

De ce credeti ca acum nu mai avem nevoie de banci si firme de asigurari? Pentru ca acum avem ... detalii

-

Mda

ACUM nu e nevoie de asa ceva .. acum vreo 20 de ani era nevoie ... ACUM de fapt nu mai e asa multa ... detalii

-

oprire pe salariu garanti bank

mi sa virat 2500de lei din care a fost oprit 850 de lei urmand sa mi se deblocheze restul sumei ... detalii

-

Amânare rate

Buna ziua, Am rămas în urma cu ratele , va rog frumos sa ma ajutați cumva , soțul a pierdut ... detalii

-

Am depus bani și nu mi au intrat in cont

Sa se rezolve ... detalii